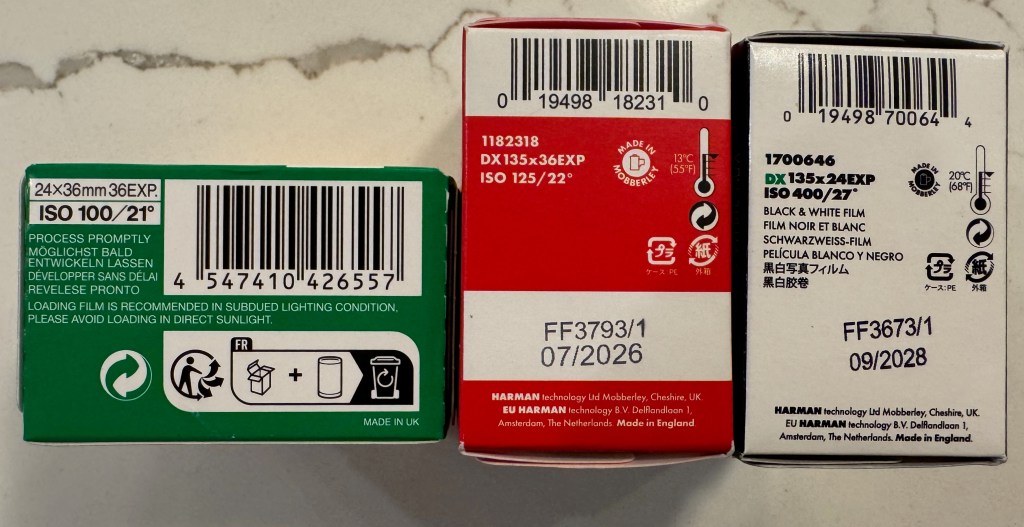

There is a store named Bellows in Little Five Points (a neighborhood in Atlanta) where they still sell a wide selection of 35mm and 120 film. I stopped by yesterday and bought film from Kodak, Harman and Fujifilm.

Back home, I looked at the box of Fujifilm Acros 100 II that I had just bought. It clearly mentions it’s made in the United Kingdom. Fujifilm? In England? A quick research confirms it: the Acros 100 II film is made by Harman Technologies Ltd, the British company that manufactures its own Ilford and Kentmere Black & White film, and also supplies B&W film for brands such as Agfa, Rollei, Oriental Seagull and … now Fujifilm. No wonder that Harman can boast of a 80% market share in the segment of B&W photo film.

The company currently known as Harman Technologies Ltd is the result of a management buy out of Ilford Imaging UK Ltd, after it went under in 2004. Founded in 1879 by a Mr Harman, the manufacturer of photographic material we know as “Ilford” still operate from their historical facilities in Mobberley, near Manchester, and have added color film to the well known range of B&W film stock (Ilford FP4 Plus, HP5 Plus, XP2, Kentmere) they produce in their plant.

Over its 146 years of operations, Ilford went through an incredible number of acquisitions, mergers, rebrands, splits, receiverships and buy-outs, and as a result Harman Technologies does not even own the “Ilford” brand.

The “Ilford” brand currently belongs to Ilford Imaging Europe GmbH, which inherited it along with the Swiss side of the old Ilford business (which used to manufacture Cibachrome and later Ilfochrome photographic papers). That side of the Ilford historical business went through its own series of plant closures, acquisitions and bankruptcies, and does not produce film or photographic paper anymore. It licenses the use of the “Ilford” brand to Harman Technologies for its B&W products, and simply distributes a range of color photographic products under the Ilford brand.

As a consequence, the current Ilford Ilfocolor film and the Ilford Ilfocolor single use cameras have nothing to do with Harman Technologies or the Mobberley plant (Harman’s own color film is sold as the “Harman Phoenix”), and are probably made by one of the companies that picked up the pieces after the East German (ORWO) and West German (Agfa) film manufacturing giants went under.

I can’t describe how this whole constellation of remote descendants of Agfa and ORWO is organized, as the situation still seems very murky, with insolvencies and lawsuits left and right. The German side of Agfa is long gone, and I don’t know if the current reincarnation of ORWO is still in operation. If they are, it (probably) makes them one of the only four companies in the world still in the color film manufacturing business, alongside Eastman Kodak and Fujifim – the heavyweights, and Harman – the new entrant (*)

At least one small (and reputable) company, ADOX, could salvage some of the industrial assets of the fallen giants (as well as some of the machines of the Swiss side of Ilford), and operates a B&W film plant in Germany.

After this detour through Switzerland and Germany, let’s go back to Fujifilm. Do you know that the Fujicolor 200 film sold over here in the US is manufactured by… Eastman Kodak. Which may not be the case in other parts of the world – Fujicolor 200 film is also packaged in China through a partnership with a local company, presumably to serve the Asian markets.

In addition to Eastman Kodak, Harman, Fujifilm and the remnants of the German photographic film industry, a few players still manufacture film: in Belgium, Agfa-Gevaert produce specialty B&W film for aerial photography, Foma Bohemia make B&W film in the Czech Republic, and Ferrania are trying to restart a B&W film factory in Italy.

Photographic film is definitely manufactured in China and possibly in the Ukraine (by China Lucky and Svema respectively) but those brands are not distributed in the US and I have no precise information about them.

The rest of the brands (Arista, Cinestill, KONO Manufactur, Leica, Lomography, Rollei, …) may commission the manufacturing of limited batches of their own proprietary film from one of the player listed above, or create their own “experimental” film by altering cinematographic film they buy mainly from Kodak, or simply re-label film produced by Harman, Foma, Adox and a few others.

As for the Instax instant film (one of the fattest cash cows of Fujifilm – $1Billion revenue with a 20% margin in 2024), it’s still made in Japan. Polaroid’s manufacturing operations are split between a main plant in the Netherlands and a smaller unit in Germany (one of the Agfa offshoots) which supplies the negative layer of the instant film. An exception in this industry, Polaroid has reunited under the same owner the brand and the plants, and manufactures and distributes its own products.

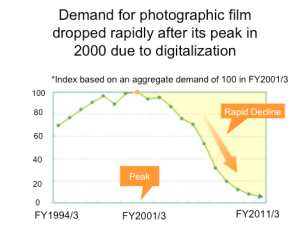

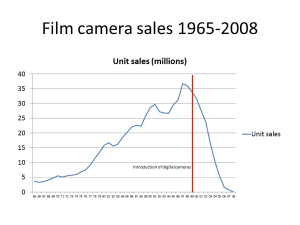

There are no reliable statistics about the total value of the photography film market in the world – I’m reading anything between $500 million to $2.5 Billion a year – a fraction of what the market was as its peak in 1999 (Kodak’s revenue alone that year was $17Billion, which would equate to $32Billion in today’s US dollar).

With the exception of Fujifilm, all the big players of the twentieth century (Kodak, Ilford, Agfa, Orwo, Polaroid) have been dismantled, with the ownership of the brands often decoupled from the ownership of the remnants of the manufacturing assets, and the actual manufacturing and distribution activities under the responsibility of new actors. It explains the proliferation of new or resuscitated brands such as ADOX, Harman, Harman Phoenix, Kentmere, Original Wolfen or Rollei.

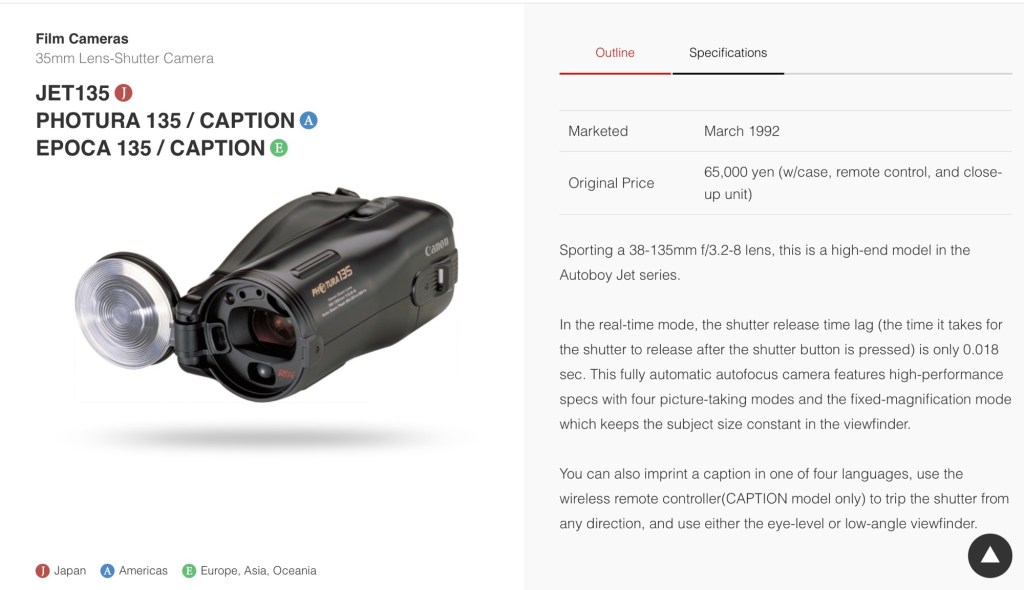

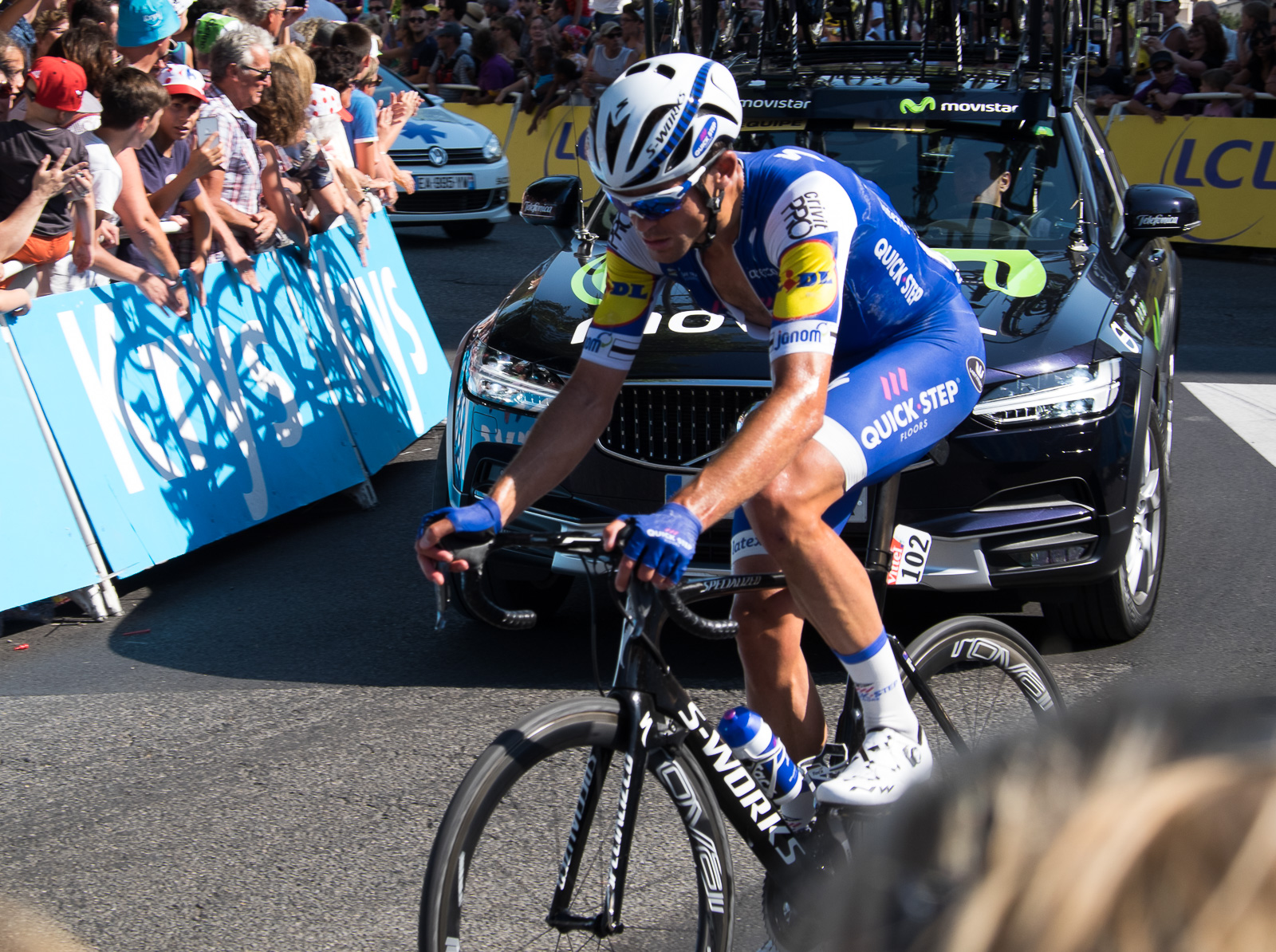

Does it matter? Not to me – as long as I can find good film to feed my cameras.

(*) Why is Harman entering the color film business, by the way ? They see a strategic opportunity in color film, obviously, and they’re also uniquely placed to take advantage of it because of their experience with chromogenic film.

Harman (as the successor of the pre-receivership British side of Ilford) has been manufacturing monochrome chromogenic film since 1981 (the XP, XP2 and now the XP2 Plus). The XP2 Plus (like the defunct Kodak BW400CN) is conceptually a simplified version of the typical chromogenic negative color film (think Kodacolor or Fujicolor), with only one layer of neutral color dyes as opposed to three layers of colored dyes in the negative color films.

In the heydays of film photography, the benefit of chromogenic monochrome film was primarily that it could be processed with negative color film, in the same machines using the same baths – the photo processing labs and the minilabs did not have to dedicate equipment and chemicals to the XP2 or BW400CN film like they would have had to do with “true” B&W film.

Two good sources of information about film photography:

Kosmofoto : the new photographic films released in 2025, so far.

More about film, film cameras and old gear in general in CamerAgX.com: