A large proportion of photographers wears prescription glasses – I know, I’m one of them – and almost everybody wears sun glasses occasionally. But surprisingly, until high eye point or high eye relief viewfinders appeared – on the Nikon F3 HP in the early eighties, photographers with glasses could not see the integrality of the scene – let alone the aperture or speed information on the LED displays surrounding the view of the scene- without having to move their eye balls up and down and left to right.

As far as viewfinders are concerned, some cameras are better than others, though. The quality of the viewfinder of a manual focus camera is influenced by three factors:

- Coverage: It’s the percentage of the image captured through the lens which is going to be shown in the viewfinder. 100% coverage is desirable – but expensive to manufacture, and only top of the line cameras (the real “pro” models) show the integrality of the scene in the viewfinder. Most SLRs show between 85% and 95% of the scene. Point and shoot cameras, (more precisely the few P&S which still have an optical viewfinder) are much worse. The best of them, the Canon G11 only shows 77% of the scene that will be captured through the eye piece.

- Magnification: If the magnification was equal to 1, an object seen through the viewfinder would appear to be the same size as seen with the naked eye (with a 50mm lens on a 35mm camera). The photographer could even shoot with both eyes open. If the magnification ratio is lower than 1, then the object will appear smaller in the viewfinder than seen with the naked eye.Magnification has an impact on composition and focusing. If the magnification ratio is very low (below 0.4) the image becomes so small that it’s difficult to compose the picture. Magnification is also a critical factor for picture sharpness on manual focus cameras: the accuracy of the focusing is directly related to what the photographer can see on the matte focusing screen, and the higher the magnification, the easier it’s going to be for him or her to focus accurately.On a 35mm single lens reflex camera, the magnification is measured with a 50mm lens, and varies between 75 and 95%. Full frame digital SLRs have viewfinders offering comparable magnification values. dSLRs with so-called APS-C sensors advertise very high magnification ratios, but after the crop factor of the small sensor is taken into consideration, the real magnification value lies between 0.46 and 0.62. Read Neocamera‘s article for more information about the real viewfinder magnification ratio of dSLRs.

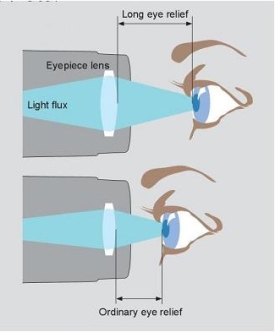

- Eye relief: “The eye relief of a telescope, a microscope, or binoculars is the distance from the last surface of an eyepiece at which the eye can be placed to match the eyepiece exit pupil to the eye’s entrance pupil.” (Wikipedia, eye relief entry).The longer the eye relief, the more comfortable the camera is going to be for a photographer wearing glasses, but the smaller the focusing screen is going to look.A photographer wearing glasses will need an eye point of approximately 20mm (depending on the dimensions of the frames and the thickness of the lenses of the glasses) to be able to see entire the viewfinder image, plus the exposure information without having to move his eye balls left to right and up and down. Camera manufacturers describe them as “High eye Point” or HP viewfinders.

A comparison between a few 35mm cameras

As is often the case with engineering, a good design is the result of a successful compromise between conflicting requirements. Most photographers desire a long eye relief, but at the same time want a magnification ratio high enough, so that they can compose their image with precision and focus accurately. With the F3, Nikon offered 2 versions of its standard viewfinder. The DE-2 of the original F3 had an eye relief of approximately 20mm, and a magnification of 80%; the DE-3 viewfinder of the F3 HP had a much longer eye relief (25mm) but a smaller magnification ratio of 75%. The market decided in favor of the longer eye relief and the DE-3 became the standard viewfinder of all subsequent versions of the F3. The advent of autofocus SLRs accelerated the trend towards longer eye relief and lower magnification ratios.

Subjective results

The experience confirms the figures. The Nikon F3 has by far the best viewfinder, followed by the tiny Olympus OM-1. The Nikon FM-FE-FA are far behind.

- Nikon launched the F3 with a standard viewfinder (model DE-2) which offered 100% coverage and already had a relatively long eye point. The standard F3 can comfortably be used by photographers wearing glasses. A few years later, Nikon introduced another version of its flagship camera, the F3 HP, which was the first to offer a viewfinder with the very long eye point of 25mm (one inch). The long eye point came at the cost of a lower magnification (down to 75%) and an higher weight. The F3 HP was a sales success, and all subsequent F3 cameras would come from Nikon with the HP viewfinder (the DE-3).

- The Olympus OM-1 has an incredible viewfinder, with a very high coverage and a very high magnification. The viewfinder does not offer any exposure information besides the match-needle arrangement at the right of the image, and even if the eye point is rather short, the photographer has the impression he’s watching all of the scene. Subsequent OM models offered a little more information at the periphery of the viewfinder and a little less magnification, and in a world where hi-point viewfinders were becoming the norm, they were far less remarkable than the OM-1.

- The Nikon FM, FE and FA provide more exposure information than the Olympus cameras (the selected aperture, in particular). Compounded with the very short eye relief (14mm), it makes it impossible for a photographer wearing glasses to see the whole scene and the exposure information at the periphery without some eye movements. While similar on paper to the other compact Nikon SLRs, the viewfinder of the Nikon FG fares worse than its stablemates in real life.

Rangefinder cameras work by different rules. Their viewfinder covers far more than what will be captured on the film, and very little exposure information is displayed in the viewfinder. Even if the Leica M offers an eye relief of only 15mm, a photographer wearing glasses will not have any problem visualizing the image in the viewfinder.

With a few exceptions such as the Canon G11, Point and Shoot digital cameras don’t offer optical viewfinders anymore. The G11’s may be used as a last resort in a very bright environment, (when using the LCD is not an option), but it’s very small and very unpleasant to use. Low end digital SLRs with small sensors (Four Thirds or APS-C) are equipped with very low magnification viewfinders, and have a very pronounced tunnel effect. Manual focusing is not an option, and composing an image with precision can be challenging. Mid-level dSLRS (like the Canon 7D or Nikon’s D90 and D300) have much better viewfinders, with relatively long eye relief (22 and 19.5mm respectively) and real magnification ratios of approximately 0.625.

More about it

Luminous Landscape – Mike Johnson’s “Understanding SLR viewfinders”

Neocamera: Viewfinder of digital cameras

- Foca *** with a Foca turret viewfinder / Olympus OM-1n. The Foca is a French rangefinder camera from the late forties, and its viewfinder is unusable if you wear glasses. And hardly usable even without them.

| Model | Coverage | Magnification | Eye Point | Comment |

| Nikon F3 HP (DE-3 finder) | 100 % | 75% | 25mm | The camera that introduced Hight Point viewfinders to the public. |

| Nikon F3 with the standard DE-2 viewfinder | 100 % | 80% | Not known. Probably 20mm | The original pre-HP viewfinder. Even with glasses one can easily see all of the scene and the little LCD display. |

| Olympus OM-1 | 97% | 92% | Not known. Probably 15mm | Incredible. How can such a small camera deliver such a large image? Short eye point, but since the viewfinder does not provide any exposure information at the periphery of the frame, not much of a problem. |

| Nikon FM, FE, FE2, FA | 93% | 86% | Not known. Probably 14mm | Short eye point, plenty of information at the periphery of the viewfinder. Not the best recipe for photographers wearing glasses. |