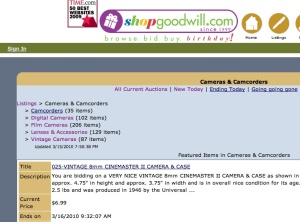

A compact point of shoot camera from the late eighties, the Contax T2, is currently red hot, selling for obscene amounts of money (well above $1,000). We’re observing here the manifestation of a new trend – a few film cameras have suddenly reached stardom – and make you pay dearly for them – while the mass of the point and shoot and SLRs from the nineties still languish in the $5.00 bargain bin.

In the world of manual focus SLRs, Contax bodies and Contax Carl Zeiss lenses, while not exactly cheap, can still be had for a small fraction of the cost of this T2.

Zeiss and its sub brand Contax have a very long history – Carl Zeiss founded the company that bears his name in 1846 in Jena (Germany) and Zeiss launched their first Contax camera in 1932.

In the seventies, Zeiss signed a licensing agreement with Yashica (the Japanese company subsequently became part of the Kyocera group). Contax and Yashica never said much about the role split in their joint venture, and most of what we know is an educated guess. High level, the “Contax” branded cameras of the Yashica/Kyocera era were designed and manufactured in Japan with some input from Zeiss. The F.A. Porsche studio (*) was in charge of the industrial design of some models. Yashica and Contax SLRs shared the same bayonet lens mount, and Contax cameras could be paired with Contax as well as cheaper Yashica branded lenses.

The “Contax Carl Zeiss” lenses were named after famous Zeiss lens designs (Distagon, Planar, Sonnar, ..) and benefited from Zeiss’ excellent multi-layer coating. Some of them were made in Germany, but the majority were manufactured in Yashica’s Japanese plants.

Because of their Zeiss and Porsche lineage, their beautiful industrial design and their advanced technical content, the Contax cameras of the Yashica era could be sold as premium products, for much more than what Yashica could have extracted from their own line of SLRs.

In Contax’s product range, the top of the line was always occupied by a camera of the RTS family, and the bottom by derivatives and successors of their original entry level camera, the Contax 139Q (137 MA, 137 MD, 159MM, 167 MT). There was room in between for what we would now call a line of “prosumer” cameras.

Contax’s middle of the range cameras were a motley crew of SLRs addressing the needs of different niches – the S2 and S2b were semi-auto mechanical cameras, the RX had “a focus assist” system, the AX was an autofocus SLR designed for manual focus lenses (the lens had to be set to the infinite, and the film chamber was moving to adjust the focus).

Among them, my pick, the Contax ST, was launched in 1992. It’s a somehow simplified and less bulky derivative of the RTS III, a full featured, motorized, manual focus camera with a large viewfinder, a bit like the Canon T90 from 1986. Its unique selling proposition was that the film pressure plate was made of ceramics rather than steel or aluminum (hint: the CERA in KYOCERA stands for Ceramics). I’m not sure that this ceramics pressure plate brought any real benefit to the photographer, but it spoke to the imagination.

Of course, at the time the camera was launched, all major manufacturers (Canon, Nikon, Pentax) had followed Minolta’s example and converted their whole SLR range to autofocus, so the manual focus ST is a bit of the odd man out.(**)

Very first impressions

It’s a beautiful, very traditional SLR which exudes quality, with no autofocus, no modal interface, no menus, no control wheel, no matrix metering, no lithium battery, and a limited use of plastics.

The ST feels dense (heavy, but not too much) and falls very well in the hands. The commands are conventional, with an aperture ring on the lens, and a large shutter speed knob and an exposure compensation dial on the top plate. Almost all controls (except for the shutter speed and exposure compensation knobs) are secured by locks (like they are on a Nikon F4). There is only a tiny LCD (view counter and ISO display) at the right on the top plate.

For the anecdote, the body of today’s Fujifilm X-T3 looks very much like a small Contax ST, at the 2/3 scale, that is. Even the location and logic of the commands is strikingly similar – with the emphasis given on exposure compensation over any other control – you don’t need to search any longer where the designers of Fujifilm got their inspiration from.

The viewfinder is exceptional. Combining a high enlargement (0.8) and a long eye point (I don’t have the figure, but by comparison with other cameras, it’s really long), it offers a cinematic view of the scene. But at the same time, it’s old school – it’s graced with red LEDs, and the focusing screen does not seem to be one of those ultra fine and ultra luminous Acutemate or BriteMate laser etched screens – as a result the image is a bit darker than what you would see on a Nikon FE2, for instance (not by much, maybe 1/2 stop). The ST is also one of the few manual focus cameras with a continuously adjustable dioptric correction – all in all one of the best viewfinders of its time.

Lesser Contax SLRs have a rubberized skin. that degrades over time – it’s not the case for the STs – they still look pristine 28 years after leaving the assembly shop.

The lens mounts and lens mount adapters

Contax and Yashica had abandoned the 42mm screw mount in 1975 with the introduction of the Contax/Yashica (C/Y) mount on the Yashica FX-1 and Contax RTS.

The original Contax Carl Zeiss lenses belong to the AE series. The design of the lenses was modified in 1985 to support the Program mode and the Shutter priority modes introduced on the 159MM – therefore the modified lenses are part of the MM series (for Multi-Mode). The two versions of the lenses are inter-compatible – you just don’t get the Program mode or the Shutter priority mode if you mount an AE lens on a body like the ST.

Other lens options

Contax Carl Zeiss Lenses in C/Y mount are rather expensive, even now. There are three alternatives if you don’t want to pay hundreds or even thousands of dollars for a lens:

- Yashica lenses: Some models have a very good reputation (the prime lenses in the ML series, generally) – they were manufactured in the same plants as the Carl Zeiss series, but were not built to Zeiss specs and did not benefit from Zeiss lens treatment. People who have tested them next to Contax lenses say the color rendering and the micro contrast are different (which makes sense – each lens manufacturer has its “signature”). Other series of Yashica lenses (DSB, YUS) are not necessarily that good – do you research.

- Third party lenses: very few independents offered lenses in the C/Y mount. Tamron and Vivitar had C/Y adapters for their respective universal mount systems. But does it really make sense to mount a Tamron or a Vivitar lens on a Contax camera?

Last but not least, you can also mount older 42mm screw mount lenses (from Yashica, Contax or other defenders of the Universal mount such as Pentax) thanks to an adapter proposed by Yashica. You can still find those adapter rings on eBay.

The elephant in the room – made in Japan or in Germany?

There is no doubt where the bodies were manufactured – my ST proudly bears its “Kyocera-Japan” signature. The Contax Carl Zeiss zoom (the 28-85 f/3.3-4.0) that came with the camera was also made in Japan (no mention of Kyocera, though).

In the early years of the Zeiss / Yashica collaboration, a lens could originate from the German workshops of Zeiss or from the Japanese factories of Yashica (even for a given model – some were produced simultaneously in Europe and in Asia). Over the years, the manufacturing activities were increasingly concentrated in Japan. I did not find any evidence that lenses made in Asia were better or worse than the lenses made in Europe – and I don’t think it matters: they were all designed and manufactured to Zeiss’s specs with Zeiss’s T* multi-layer coating.

Buying Contax cameras and lenses today

In the nineties, Contax cameras were positioned and priced as premium products, a big notch under Leica, but in the same ballpark as Nikon’s or Canon’s Pro cameras.

Today, their high-end bodies hold their value very well even if Leica R products remain more expensive.

The Contax magic percolates to Yashica ML lenses and to certain Yashica bodies (like the FX-3 Super 2000), which are also sold at a premium, for products of a second tier brand, that is. The 21mm and 28mm wide-angle lenses are particularly sought for, selling for at least $350.00.

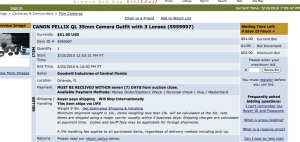

The least expensive Contax SLRs are the entry level models (139, 137, 167) at less than $100.00 for a nice copy. Really sought after models like the RTS III, the S2 (the semi-auto camera) or the Aria (a compact SLR, the last camera in the Contax manual focus line and the only one with matrix metering) typically sell in a $350.00 to $600.00 bracket. The rest of the products (ST, RX, RTS I or RTS II) sell for approximately $150.00.

But be cognizant that in order to enjoy the full Contax experience, you’ll need Contax Carl Zeiss lenses. It’s very difficult to find anything (even a very common Planar 50mm f/1.7) at less than $150.00, and really interesting lenses (the 21mm wide-angle for instance) can cost well over $1,000.

More about the Contax ST and the Vario-Sonnar 28-85mm f/3.3-4.0 in a few weeks, after a few rolls of film.

The Contax brand has been dormant since 2005, and there is relatively little information about their products on the Web.

The best source is a site maintained by Cees de Groot: http://cdegroot.com/photo-contax/

Apart from that, you have Wikipedia (of course): http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Contax/Yashica_lenses and a few sites compiling user reviews of SLR lenses.

(*) Porsche used to be a family business. And everybody in that family seemed to be named “Ferdinand”. Because it was a family business, the eight grand-sons of Ferdinand Porsche, (the engineer who had founded the company and designed the original Beetle) ended up working at the Porsche car company under the direction of Ferdinand “Ferry” Porsche, who had taken over the business from his father Ferdinand after WW2. When the conflicts between the most talented of the cousins reached dangerous levels, Ferry asked them to leave. Ferdinand Piech, who had designed the engine of the 911, left to start a new career at Audi, and ended his professional life as the chairman of the Volkswagen Group. The other cousin, Ferdinand Alexander Porsche, who had designed the body of the original 911, started his own design studio. And one of the first clients of the studio was… Contax.

(**) – Contax launched its first autofocus film SLRs (the N1 and the NX) in 2000 with a new lens mount and a new series of lenses – roughly 15 years after anybody else. And followed up with the first full-frame dSLR in 2002, the Contax N Digital. The products did not sell well and were rapidly withdrawn from the market, and Kyocera left the photography market for good in 2005. The Contax brand has been kept dormant ever since.

The lens mount of the Contax N, N1 and Nx of the early 2000s was totally different from the C/Y mount of this ST. From an engineering point of view, the new lens mount was so close to Canon’s EOS that conversion jobs were possible. You can read a test of a converted lenses in Optical limits

More about the N series:

https://sunrise-camera.com/the autofocus-slr-camera-contax-n1

Luminous Landscape on the Contax N Digital

From the Contax ST brochure (available at: https://panchromatique.ch)