The price of a digital camera on the second hand market is more or less proportional to the number of pixels of its image sensor – interchangeable lens cameras (dSLRs and mirrorless) with anything between 24 and 50 Megapixel (Mpix) sensors are considered current and command big bucks, while models with less than 10 Mpix are deemed virtually worthless.

Case in point – I bought a Pentax *ist DS (a 6 Mpix dSLR from 2004), a bit scruffy but in working order, for less then $35.00.

So, it’s cheap, but is it still usable?

Why the Pentax *ist DS back then?

At the turn of the century, the photography market was different from what it was to become a few years later – there were only four companies in the world selling digital SLRs (Canon, Fuji, Kodak and Nikon). And those cameras were very expensive, and primarily bought by news agencies and well heeled pros.

2002 saw a first wave of more affordable digital SLRs reach the market (Canon, Fuji and Nikon all launched models in the $2000 price range). Pentax and Olympus joined the fray in 2003 with the *ist D and the E-1. At the end of 2003 Canon made digital SLRs affordable for amateurs with the Rebel 300D, the first dSLR to sell for less than $1000.00.

Nikon and Pentax followed rapidly with two models priced around $1000, the D70 and the *ist DS. Like millions of amateurs, I was looking for my first digital SLR in those days, and the *ist DS was my pick. Its specs were not that different from the D70 or the Rebel. What made the difference for me was its small size, its large viewfinder, and the good reviews of its kit lens.

Of course, I sold it after a few years to upgrade to a 10 Mpix camera, which itself was sold a few years later to fund the next upgrade, and so on.

Why a *ist DS now?

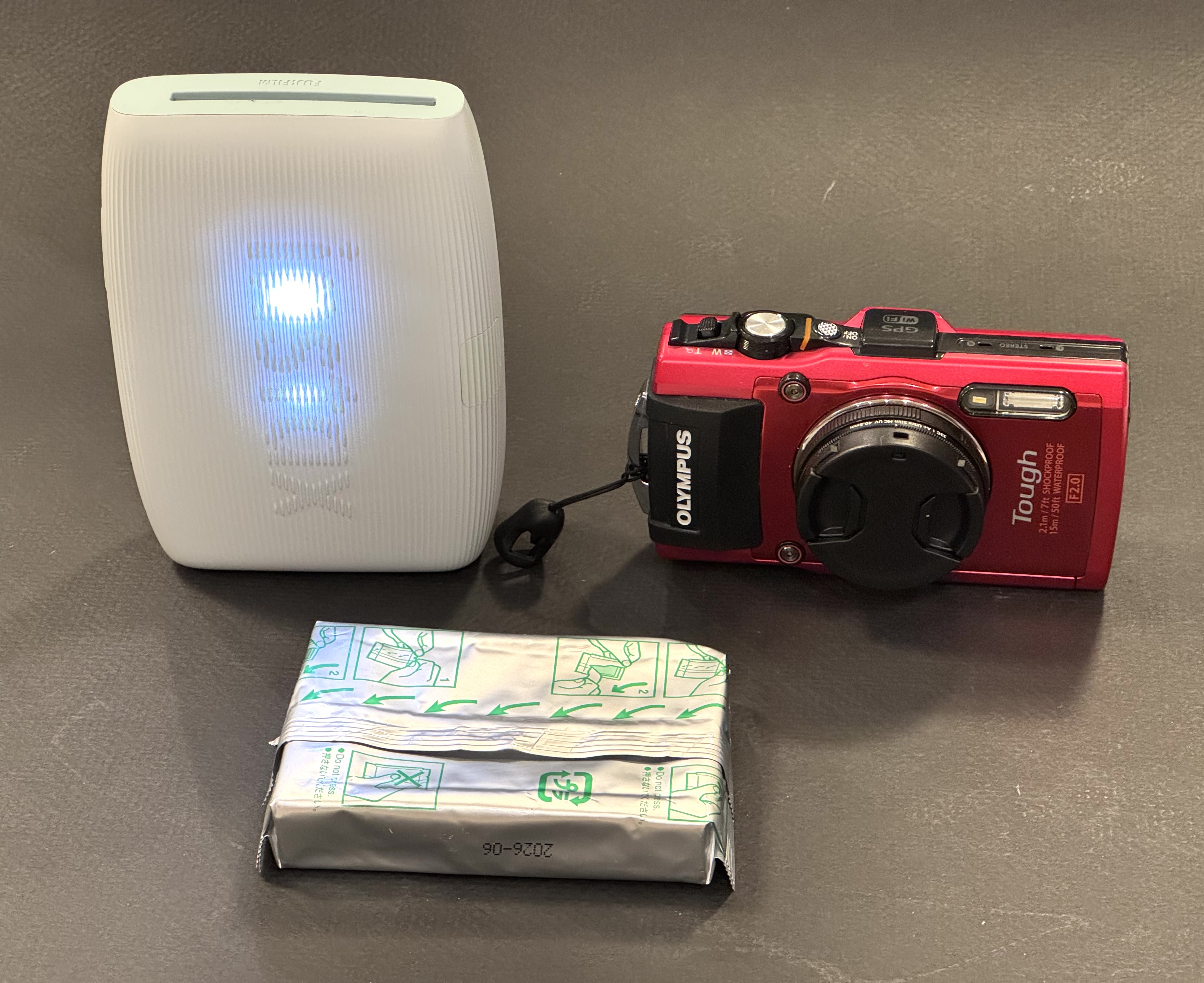

A few months ago, I bought a colorful Pentax K-r (a 12 Mpix camera from 2010) and was surprised by the quality of the RAW files it delivered. You pay a bit more for the colored body of a K-r, but all white and all black models can be found for less than $100.00. In my recollections, the *ist DS was a good little camera, and I was wondering what it would be like to shoot with a 6 MPIX dSLR now. I started checking the usual auction sites, and $34.00 made me the proud new owner of another Pentax camera.

First impressions

I had shot a few thousand of pictures with my *ist DS in the early 2000s, so this “new” *ist DS is not really a total unknown for me.

What struck me immediately when I received my $35.00 *ist DS is how similar it looked to the K-r; as if Pentax had kept the same moulds over the 7 years that separate the two cameras. The *ist DS is smaller than Nikon’s mid-range APS-C of the same vintage, but the general organization of the commands is strikingly similar to what current Pentax and Nikon APS-C dSLRs look like – to a large extent the dSLR camera had already found its final form in 2004.

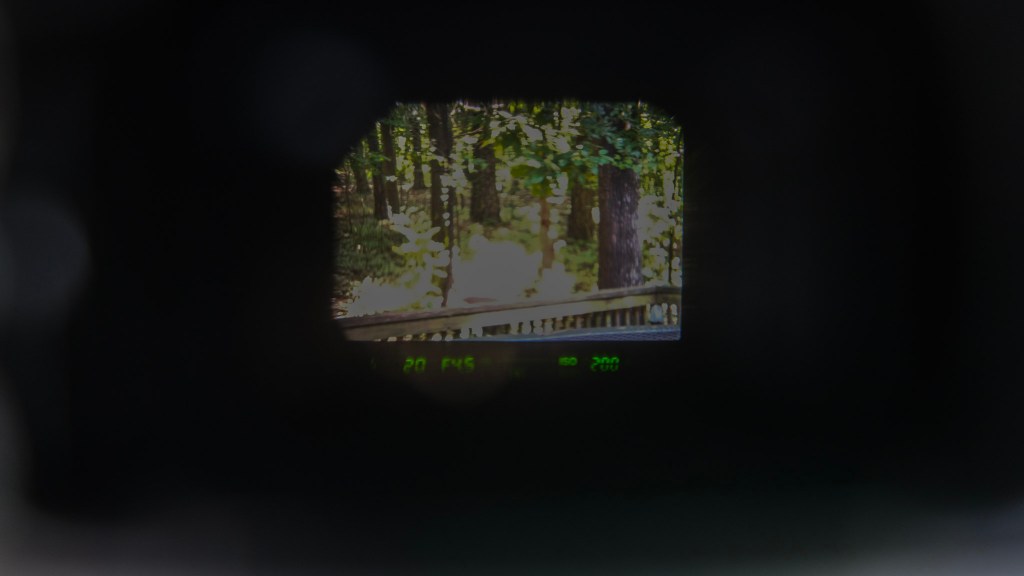

Visually, the biggest difference is the rear LCD display – the DS’ is very small (2in diagonal, some smart-watches have larger displays), and its dynamic range very limited.

My $34.00 camera is old, and definitely not in tip-top shape (the mode selector is stuck in the Auto-Pict position, the integrated pop-up flash seems to be dead), but it still works well enough to get an opinion about this generation of 6 Mpix cameras.

Back in 2005, DPReview was very happy with the responsiveness of the camera, but concerned with the quality of its JPEGs. Today, the standards are different, but the responsiveness is still OKay-ish – when there is enough light for the autofocus to operate – otherwise it hunts desperately.

As for the image quality, even in RAW, it’s often disappointing.

The camera is twenty years old, may have been treated badly by some of its owners, and may not perform as well as when it was new, but, in any case,

- the dynamic range of the sensor is limited (DXO evaluates it at 10 EVs, as opposed to 14 EVs for the sensor of a more recent Pentax K-5 for instance). If the scene is lit evenly, the results are correct, but even Lightroom can’t save RAW images like the picture of this old church or that plant on my deck.

- I’ve been used to shooting with cameras and lenses equipped with image stabilization mechanisms, which this *ist DS is deprived of. Images which would have been technically good with a camera from the 2010s are blurry because of camera shake,

- the autofocus is a hit or miss – it works fine on static scenes, not so well if the subject is moving or the scene too dark.

Conclusion

Obviously, this camera works, and in ideal circumstances, will deliver usable images. But even if the images are saved as RAW files, the highlights are often desperately burnt, and the shadows too dark. The autofocus struggles with moving subjects, in particular if they’re not perfectly centered, and because this model is deprived from image stabilization, images will be blurry if the photographer does not pay close attention to the shutter speed. Very clearly, there is a huge image quality and usability gap between this *ist DS and cameras launched six to seven years later.

In the days of $5.00 Starbucks Lattes and $10.00 McDonalds Value Meals, $34.00 is not a huge sum to spend on a digital camera. But if you put the equivalent of six more Value Meals on the table, you’ll get a much more usable Pentax K-r (or any equivalent 12 Mpix dSLR from the early 2010s). Add another five will get you a really nice 16 Mpix dSLR like a Pentax K-5, or an already modern mirrorless camera such as the Panasonic G2 (12 Mpix) or the Sony Nex 3 (14 Mpix).

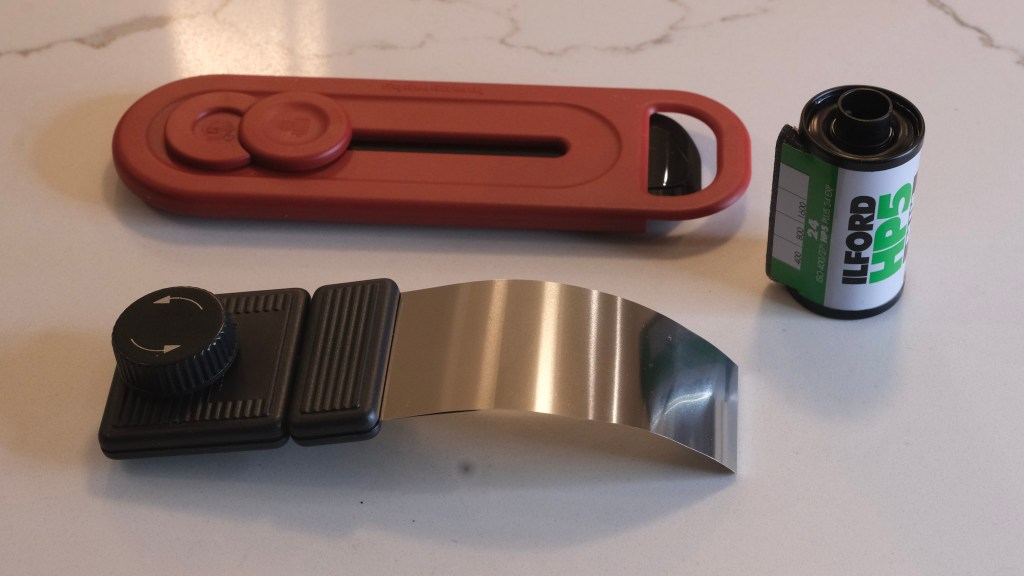

I’m not necessarily attracted to the latest and greatest features of the newest cameras (I also shoot film with cameras from the 1980s…), and will be happy to shoot with a digital camera deprived of movie mode or of wifi/bluetooth connectivity, if it still delivers images of good quality, most of the time.

But if the performance of a camera (by modern standards) is so limited that I start missing too many potentially good pictures, the quest for minimalism goes too far to my taste.

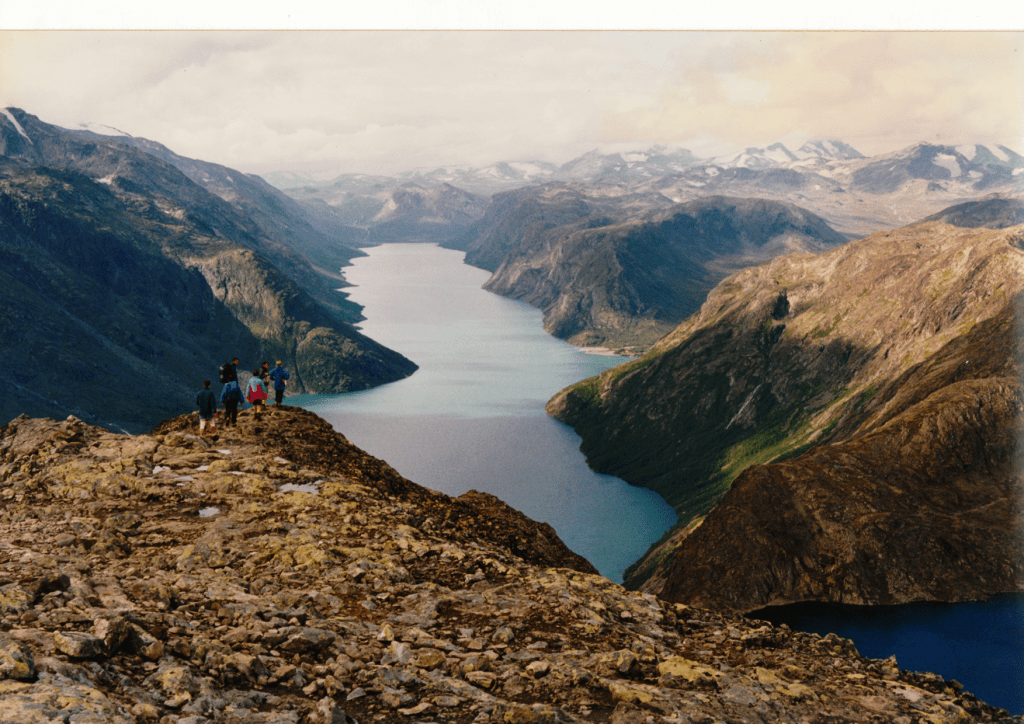

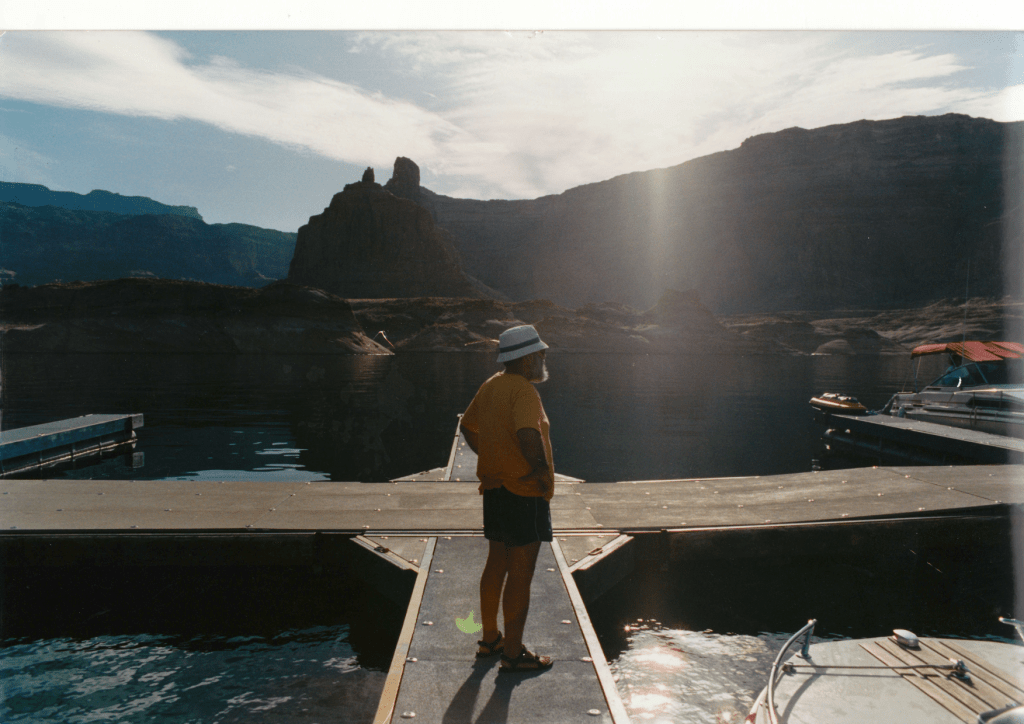

It is true that when cameras like the Pentax *ist DS (and its Canon, Konica-Minolta or Nikon 6 Mpix competitors) were launched in 2004, we were impressed by the huge step they represented over the digital point and shoot digicams we’d been using for a few years, and even today, we’re still proud to share the best images we got from those early dSLRs. If I set it up carefully, and use it within the limits of its performance envelope, I’m sure that even my scruffy *ist DS will get me decent pictures.

But today, I see the Pentax *ist DS more as an interesting curiosity, than as a camera I could use day to day. In the six years that separate a Pentax *ist DS from a Pentax K-5 (or a Nikon D70 from a D7000), there has been a huge step forward in reactivity, resolution, dynamic range and low light image quality, a step so large, that if I had to chose, I would spend a bit more on a dSLR or a mirrorless camera of the early 2010s, and forget about the *ist DS.

More about Pentax cameras in CamerAgX

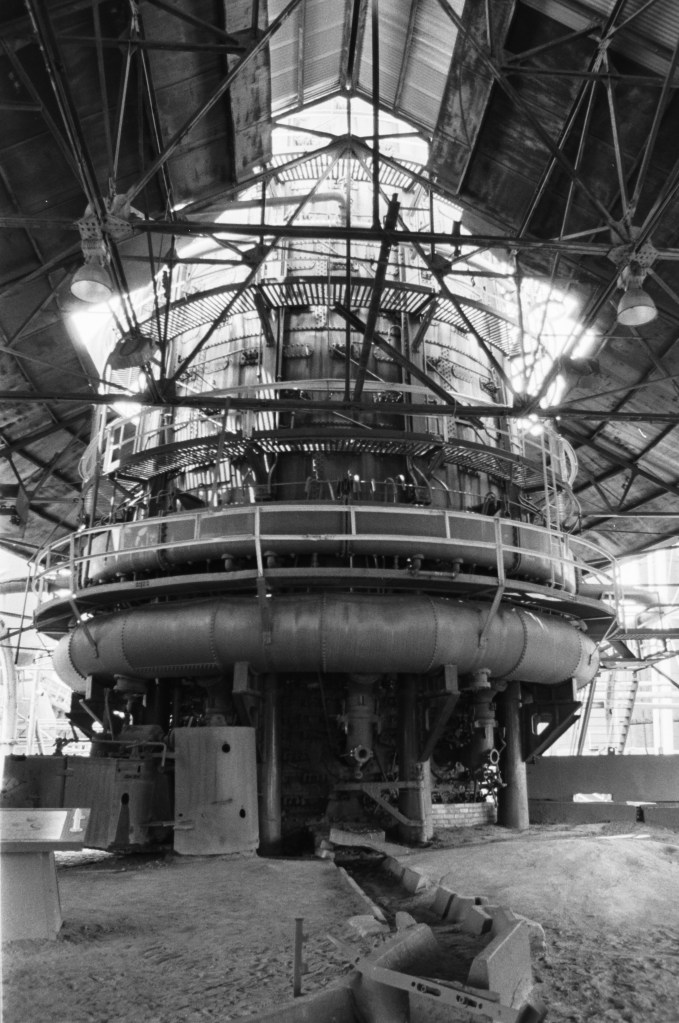

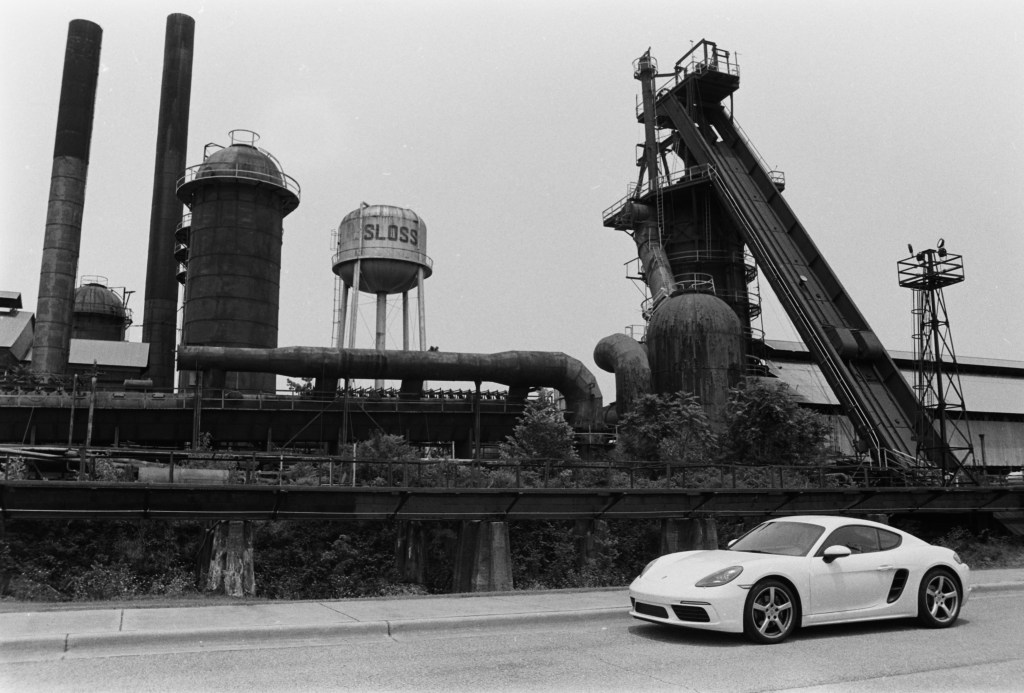

Pictures from my first *ist DS, shot between 2005 and 2007