The Pentax KP – an APS-C Digital SLR competing in the same category as the Nikon D7500 and the Canon 90D – was presented in a recent blog entry. It was sold between 2017 and 2021, and was spec’d to slot between the “amateur” oriented Pentax K-70/KF, and the very expensive Pentax K-3 Mk III.

The K-70/KF and the K-3 have bodies which are very conventional for dSLRs (and make them easy to live with), but the design of the KP is reminiscent of the manual focus SLRs of the eighties (and of the very successful Fujifilm X series mirrorless cameras), which creates some ergonomics and battery life challenges.

Without a direct legacy in the current Pentax line-up, the KP remains a very interesting proposition for Pentax shooters – with a 24 Mpix sensor and a processing engine of recent design, it is still up to date when compared to mid level APS-C mirrorless cameras. In fact, in terms of image quality and high ISO performance, it’s only second to the much more expensive K-3 Mk III in the Pentax APS-C line-up. And contrarily to its K-3 biggest brothers, it has an articulated rear display, which makes composing the image in “Live-View” mode easier.

Shooting with the KP : the optical viewfinder

Because it’s Pentax’s main differentiator, the optical viewfinder of their dSLRs is the object of the utmost care – and the truth is that – for an APS-C camera, the KP has a very good OVF. The specs sheet reads like a dream come true. The OVF’s pentaprism is made out of glass, it covers almost 100% of the captured image, with a magnification factor of 0.95x and an eye relief of 20.5mm. The focusing screen is fine and bright enough to let you set the focus “manually” with pre-autofocus era lenses.

It’s still an APS-C (meaning cropped sensor) camera, which makes some of the figures of the specs sheet misleading – the announced magnification factor of 0.95x would translate into a relatively mediocre 0.63x on a full frame dSLR (a Pentax K-1 or a Nikon D780 reach 0.7x, and the very best full frame cameras 0.76x). The viewfinder does not exactly give you the immersive view you get in the OVF of a professional full frame dSLR – but composing your pictures through the viewfinder of the KP is still a very pleasant experience – it is large and luminous enough to let you judge how the image will look like without having to double check the rear digital display all the time – it’s very significant step up over the “dark tunnel vision” experienced with the entry-level dSLRs from some other manufacturers.

There is no electronics to introduce a delay between what happens on the scene and what you see on the focusing screen, and – for whatever reason (I know, old habits and old age…), I find it easier to mentally project the final image when I compose on the focusing screen of an optical viewfinder rather than on the LCD panel of an electronic viewfinder.

Shooting with the KP: The third control wheel

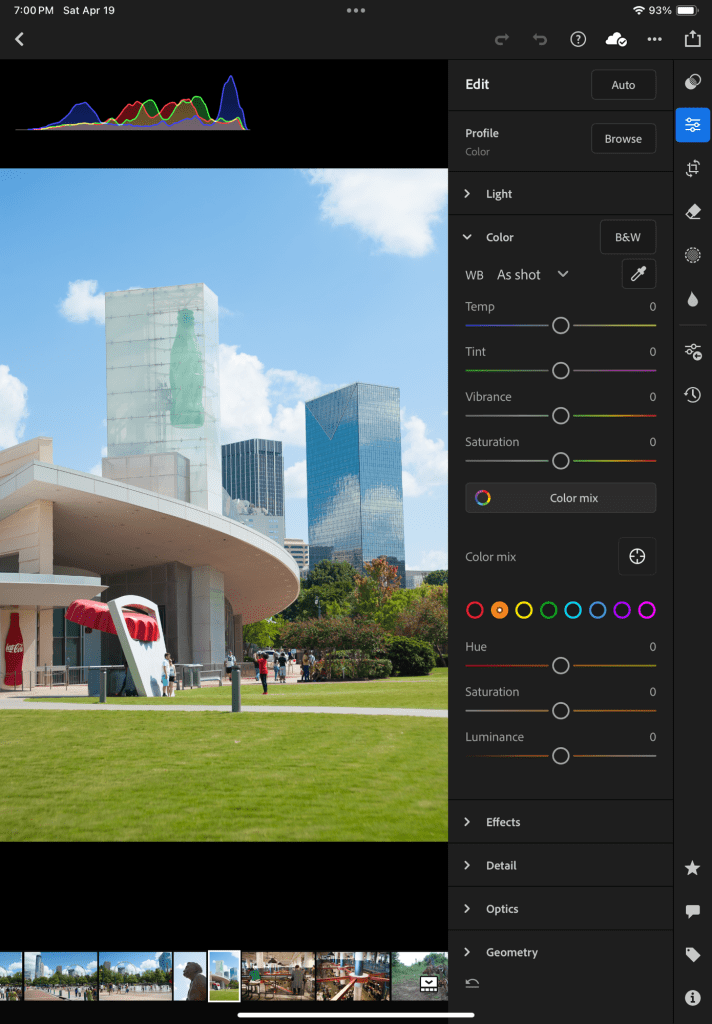

Like cars, cameras are software defined those days. Everything can be configured and menus have become incredibly long and complex. The KP is not different, but Pentax has introduced one trick to make the photographer’s life easier, the “third control wheel”.

On a relatively compact camera like the KP, the real estate where to place dedicated buttons and switches is limited, and the quantity of options and settings offered in the menus can be overwhelming.

There are settings for which no dedicated physical control is available but that you may wish to change without having to dig deep into pages and pages menus. That’s where the third control wheel – the so called “smart function dial” comes into play.

The “smart function dial” is a big knob on the top plate that can take one of six positions – three pre-defined by Pentax, and three user-defined. Imagine you’re in front of a high contrast scene – you know you’re going to need to set the camera to HDR mode, but don’t know how to configure it. Place the big dial on the HDR position, and rotate the third control wheel at the far right of the top plate to select the desired HDR setting. Take the picture, review the result, then simply rotate the third control wheel left of right to select another HDR setting, and repeat until you get a picture you like.

In my experience, the real value sits with the user configurable functions, C1, C2 and C3. I’ve set C1 to change the exposure compensation value. If I’m facing a scene difficult to evaluate, I position the knob on C1, and use the third wheel to circle through the different exposure compensation values. Similarly, I configured C2 to easily switch from an ISO value to another.

The third control wheel may seem gimmicky, or redundant (I could also access the exposure compensation or the ISO settings using a dedicated key and the second control wheel or the Info page on the rear display), but it saves time if you need to change a parameter frequently or if you’re trying different options when facing a complex scene, and I ended up using it a lot.

Not so good: Battery life

Well, it’s not brilliant. Not as bad as a Fujifilm X-H1, for instance, but not great at all, and frankly disappointing for a dSLR. Because there was no room in the KP’s body for the large battery of the K-5/K-3 series, Pentax used the small 1050 mAh battery introduced in 2010 with the K-r, and typically coming with Pentax’s entry level models (it’s still being used in the KF). For reference, the K-5 and the K-3 use a 1860 mAh battery, delivering almost twice the capacity.

The KP is begging to be used in Live View Mode (why would Pentax have specified a tiltable rear screen otherwise), which increases the power consumption and makes the choice of a small battery even more puzzling. When Nikon dSLRs can easily shoot 1000 pictures on a charge, the KP is struggling to deliver more than three hundreds (it’s rated at 420 shots per charge by CIPA, which seems pretty optimistic). Be sure to have one or two charged spare batteries with you, or the battery grip attached.

The battery grip accepts one lithium battery (either the small type of the KP/KF or the large type of the K-5/K-3) and its capacity comes in addition to the battery already in place in the body of the camera, effectively doubling the total battery capacity (with the small KP/KF battery) or almost tripling it (with the large K-5/K-3 battery).

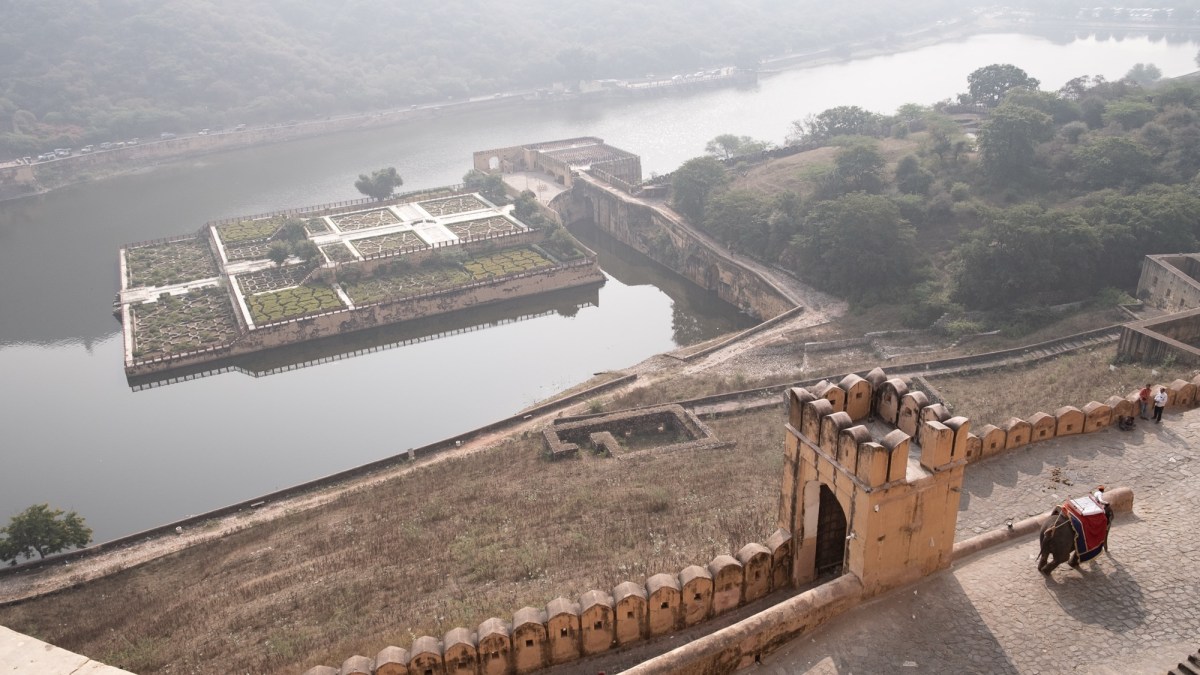

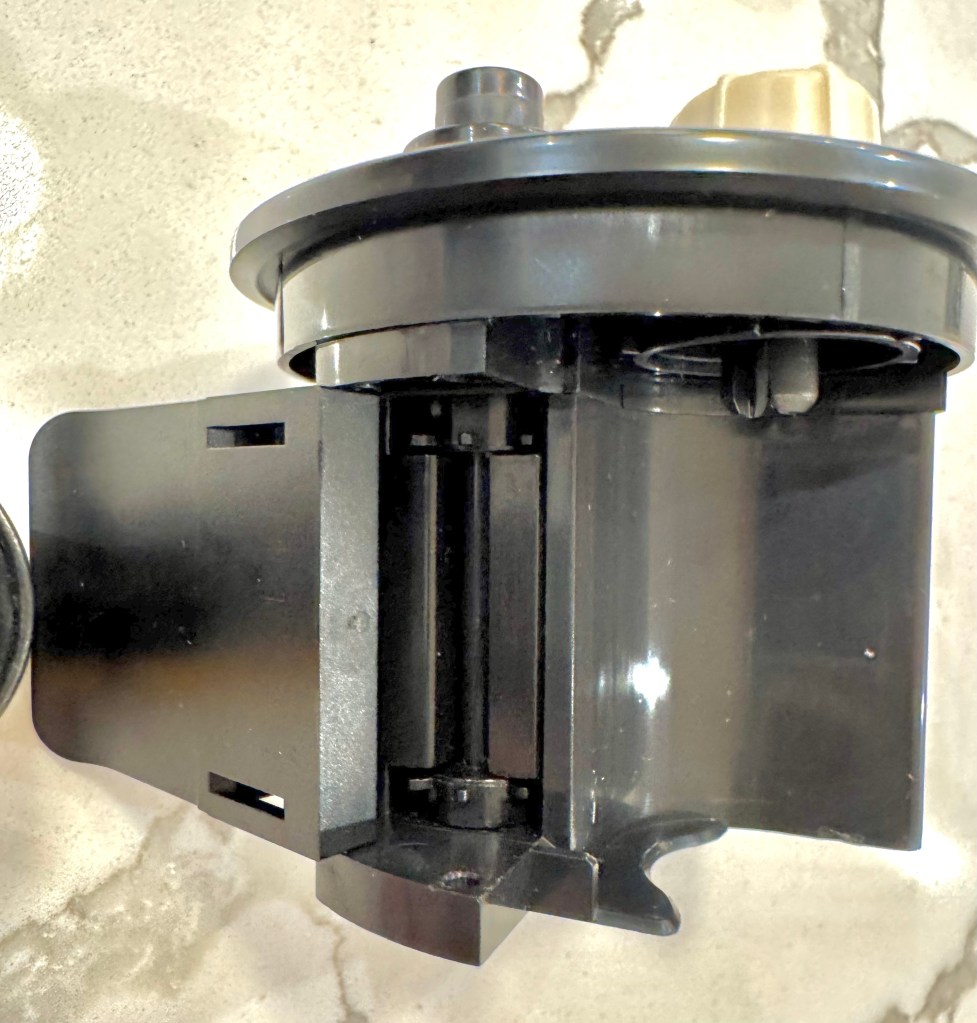

The Live View mode and macro-photography

This is not a mirrorless camera, and even though the image sensor has photosites dedicated to phase detection autofocus, they are only mobilized when shooting videos, and not when taking still images.

Therefore, when in the Live-View mode, the KP won’t have the speed and reactivity of a good mirrorless ILC (to shoot sports, wild life or other moving subjects, use the optical viewfinder, that’s what it’s here for). But on relatively static and evenly lit subjects (landscape, interior photography, macro photography), the autofocus of the Live View mode works extremely well.

On other subjects (moving objects or people, scenes with strong highlights), it struggles, and hunts vainly for focus (I’ve read it performs better with recent lenses equipped with an internal focusing motor). On earlier Pentax models, Live-View looked like a clunky afterthought. Here, it’s well implemented but only usable with a limited type of subjects.

Image Quality

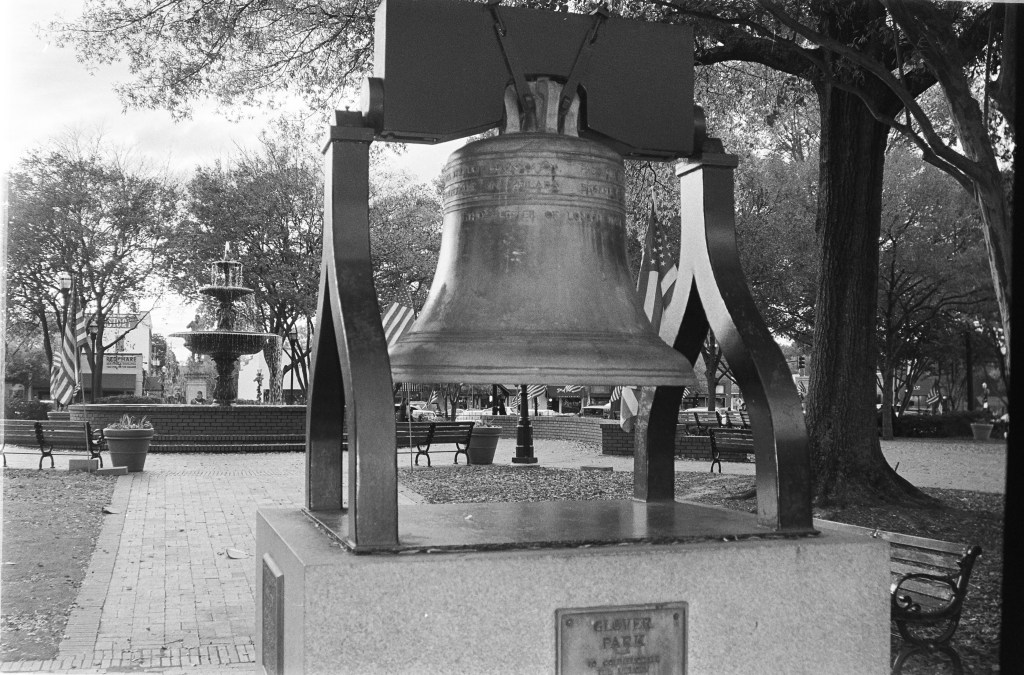

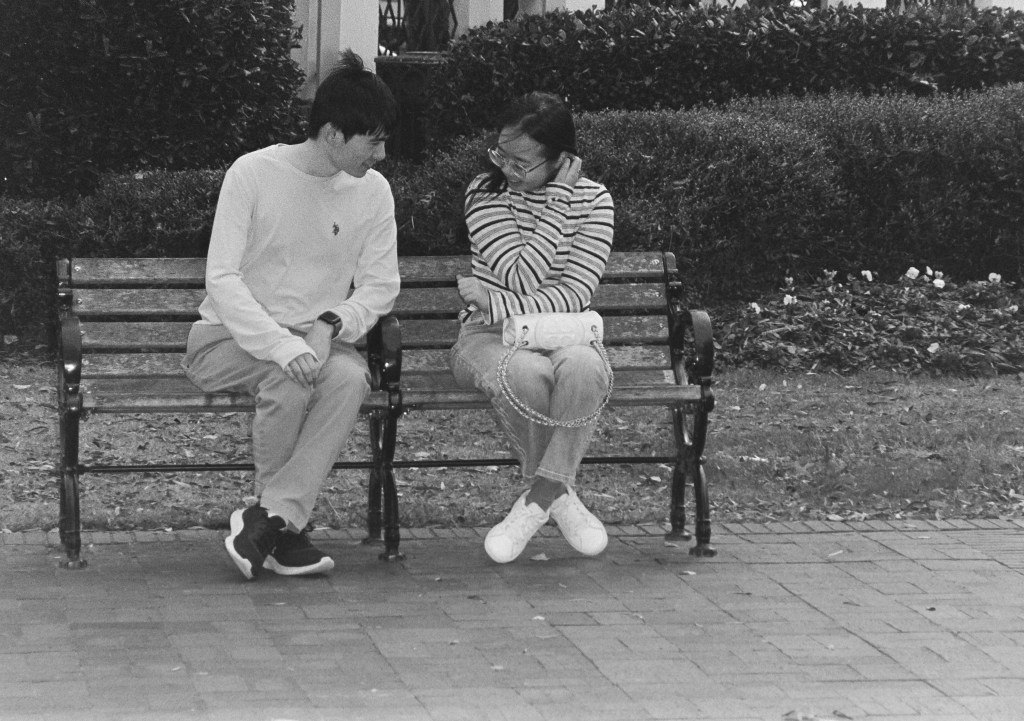

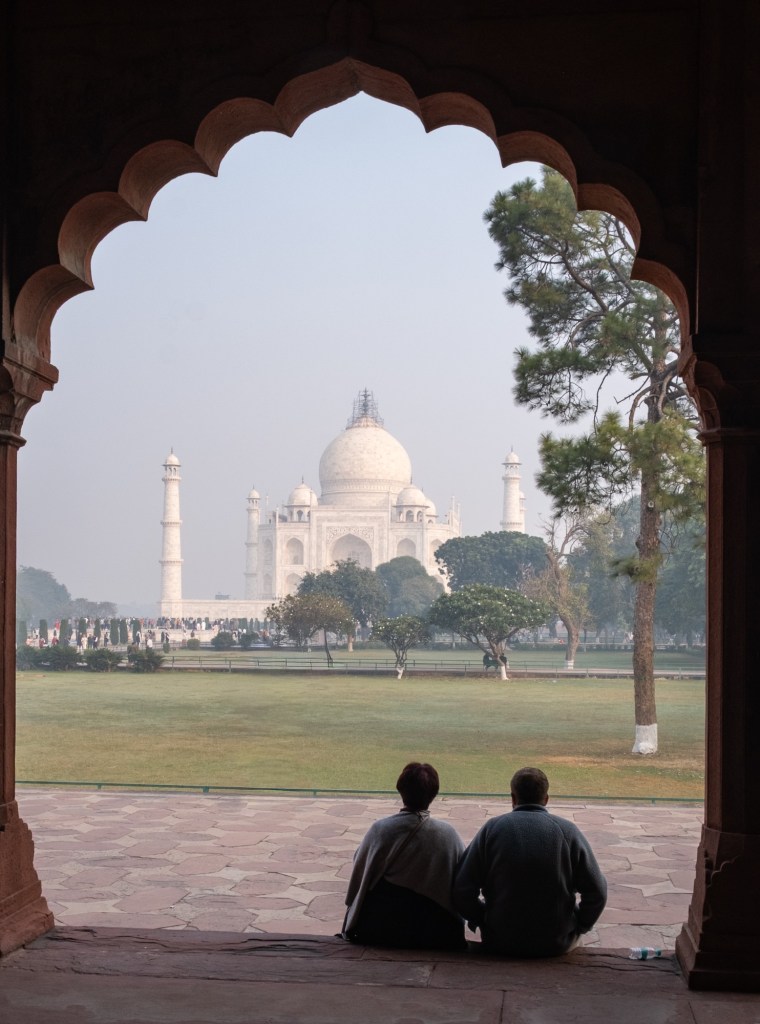

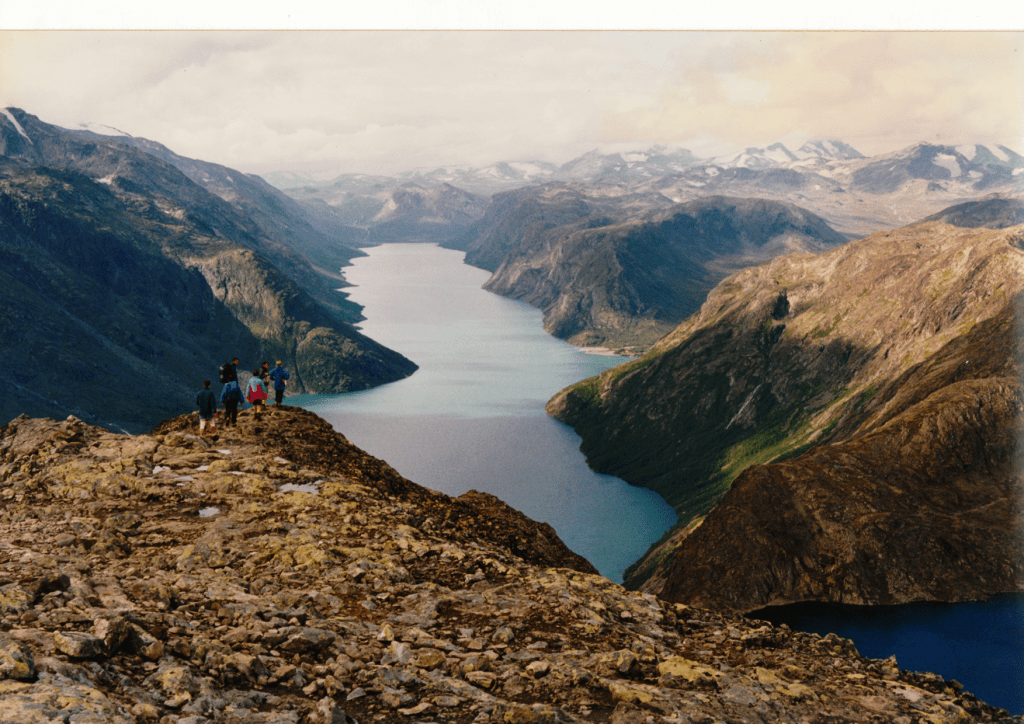

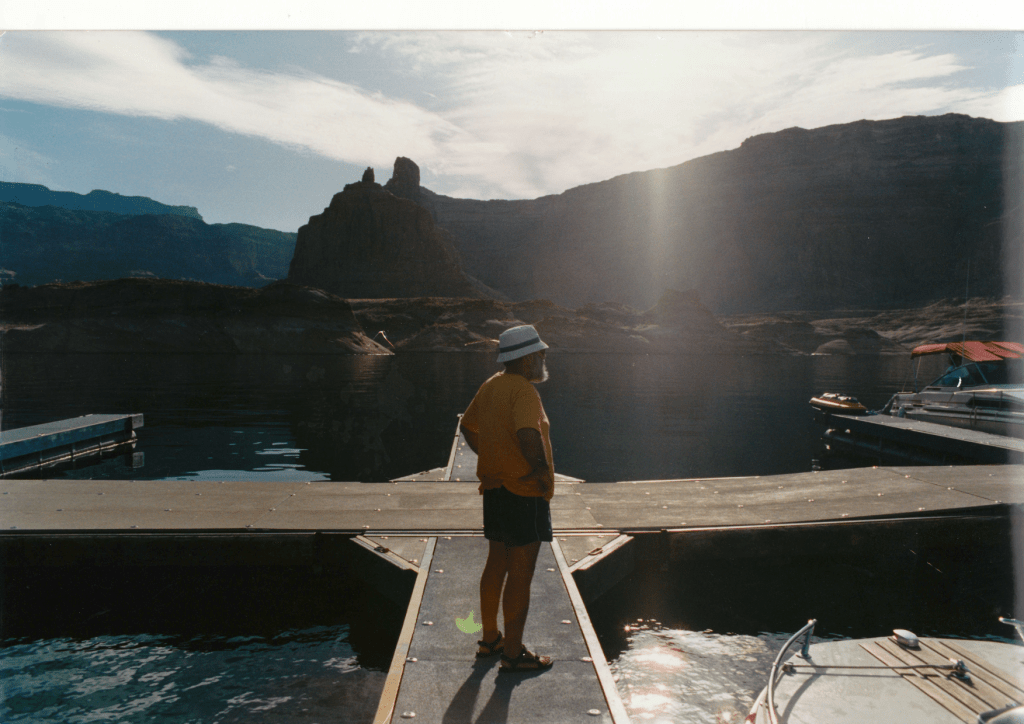

I don’t know if it’s the camera, or the prime Pentax 35mm Macro “Limited” prime lens . Or the combination they form. But I’ve been really pleased and genuinely impressed with the quality of the images.

The images (RAW and JPEGs) are correctly exposed, with pleasing colors, they show an impressive dynamic range, and need very few adjustments – no need to play with the exposure, the highlights or the clarity sliders to get pictures you can be proud of. And it’s true for landscapes, for interiors, for pictures of objects, when composing through the optical viewfinder and on the rear display in Live-View mode.

You can see Pentax dSLRs as obsolete pieces of machinery, and you would have a point when it comes to their live-view or video capabilities, but as far as still image quality is concerned, they’re perfectly up to date.

A mirrorless killer?

No way.

The KP is a niche product. You shoot with a KP either because you’re a committed Pentax dSLR photographer and will not consider any other camera system, or because from time to time you want to enjoy to experience of composing your images through an optical viewfinder, with a camera whose user interface you can configure in depth and to your liking.

Objectively, compared to the best mirrorless ILCs, the KP’s autofocus is not as capable (it only offers face detection in live view, for instance, not when composing through the optical viewfinder), the autofocus in the live-view mode only works well with relatively static and evenly lit subjects, video capture is comparatively primitive and most surprisingly for a dSLR, battery life is sub-par (recent mirrorless cameras do better). As for the ergonomics, it’s an acquired taste – the KP is extremely compact (smaller than a Fujifilm X-T series for instance), but also heavier and not as pleasant to hold if paired with its small grip.

Image quality is extremely good and pictures have a pleasant “Pentax Touch”, but the best mirrorless cameras are no slouch either, and nowadays a lot can be accomplished with presets and filters in image editing software. Last by not least, the vendors of APS-C mirrorless cameras – Canon, Fujifilm, Nikon or Sony – all have a significant market presence and a clear product roadmap, which can’t be said for Pentax.

So, what’s left? The thing that mirrorless cameras can’t offer: the direct, immediate view of the scene through an optical viewfinder. That, and the fact that the user interface is so rich in buttons, knobs and control wheels that the camera can be configured to work exactly like you feel it should. The KP is a genuine pleasure to shoot with and naturally pushes the photographer to explore and experiment.

Except to pay between $550.00 and $750.00 for a used KP located in the US. Pentax cameras used to have a much stronger following in Japan than in America, and most of the used KPs are located there. They will be subject to tariffs and fees if imported into the US. Tariffs and fees may (or may not) be included in the announced shipping costs. It’s a point to validate before placing the order.

More about the KP:

- DPReview: https://www.dpreview.com/reviews/pentax-kp-review

- Pentaxforums: https://www.pentaxforums.com/reviews/pentax-kp-review/introduction.html

- PentaxUser: https://www.pentaxuser.com/review/pentax-kp-dslr-review-1038

- Kobie MC on Youtube: https://youtu.be/N5fAc45_UdE?si=iMBC23n53vBdcwA9

For a similar budget, should you buy a used K-3 Mk II or a used KP?

The KP is a more modern but somehow quirky evolution of the K-3 Mk II. Its image sensor is more recent, its image processing engine more elaborate, and it will deliver marginally nicer pictures, particularly at high ISOs. The third control wheel is also unique to the KP, and more useful than I thought.

The tiltable rear screen is in my opinion the main reason to prefer a KP over a K-3 II. It makes the camera easier to use for macro photography, when shooting with a wide angle lens or from the hip in the street, all situations where the live-view option can be put to better use with a tiltable LCD. Alternatively, its more conventional design is the main reason to prefer a K-3 Mk II, in particular if you shoot with long and heavy lenses, and believe that the tiltable rear screen is going to make the KP too fragile in the long run.

K-3 Mk II or KP, it’s up to you – but be warned: it may whet your appetite for an even more modern take on the classic Pentax optical viewfinder camera theme, the K-3 Mk III.

More on my Flickr gallery