I’ve bought a few old Pentax cameras recently, film and digital, and out of curiosity I’ve started following what’s happening in the world of Pentax aficionados.

There was a passionate discussion recently on Pentaxforums.com, started by a photographer who was disappointed by his recent mirrorless camera system, and was considering selling everything to go back to a Pentax dSLR (he was balancing between a K-1 Mark II and a K-3 Mark III).

I am not going to pronounce him right or wrong – what he likes to shoot with or how he spends his money is his business, not mine. But not that many photographers are still interested in new dSLRs.

The fact is that digital single lens reflex cameras (dSLRs) form a rapidly receding niche, and that in the battle for the dollars of photographers (enthusiast amateurs, influencers, vloggers and pros alike), mirrorless cameras have won. A few data points to illustrate it.

When were the last dSLRs launched?

Olympus stopped selling dSLRs in 2013, and Sony officially discontinued their SLR and dSLR “A” Mount in 2021 (their last dSLR was launched in 2016). Canon’s most recent dSLR is the Rebel 8 from 2020, Nikon’s latest is the d780 from 2020, and Pentax’s is the K-3 Mark III, introduced in 2021. A variant of the K-3 with a monochrome image sensor was introduced in 2023, so that would make the K-3 III Monochrome the most recent of them all.

Canon and Nikon have not shared any plan to launch a new dSLR in the future (it’s likely they won’t), but since the launch of the Rebel 8 and d780, they have launched 14 and 11 mirrorless interchangeable lens cameras, respectively.

Who is still manufacturing dSLRs?

It’s difficult to know for sure what is still being manufactured – what we see on the shelves of the retailers may be New Old Stock or the output of small, infrequent production batches. Some models (like the Nikon D6 or the Pentax K-3 Mark III) have been withdrawn from some markets already, and other models – while not officially discontinued – may not be manufactured “at the moment”.

I checked the Web site of B&H, and here’s what’s still available new in the United States (with the official warranty of the manufacturer).

- Canon still have six dSlRs on their US catalog, ranging from the Rebel to the 1Dx (three APS-C cameras, three full frame)

- Nikon are proposing four models: the APS-C d7500, and three full frame models: the d780, d850, and D6,

- As for Pentax, they are still proposing three cameras with an APS-C sensor, the KF, the K-3 Mark III and the K-3 Mark III Monochrome, and a full frame camera, the K-1 Mark II.

Why did mirrorless win in the first place?

The Nikon D90 from 2008 was the first SLR capable of recording videos. But the architecture of a single lens reflex camera (with a flipping reflex mirror and an autofocus module located under the mirror) forced Nikon to design a camera that operated differently when shooting stills and videos.

For stills, the D90 worked like any other dSLR ( with a through the lens optical viewfinder and phase detection AF). When shooting videos, the reflex mirror was up, and the viewfinder could not be used. The operator had to compose the scene on the rear LCD of the camera. The phase detection autofocus system was also inoperant. A second system, based on contrast detection, had to be implemented, and could only be used before the videographer started filming.

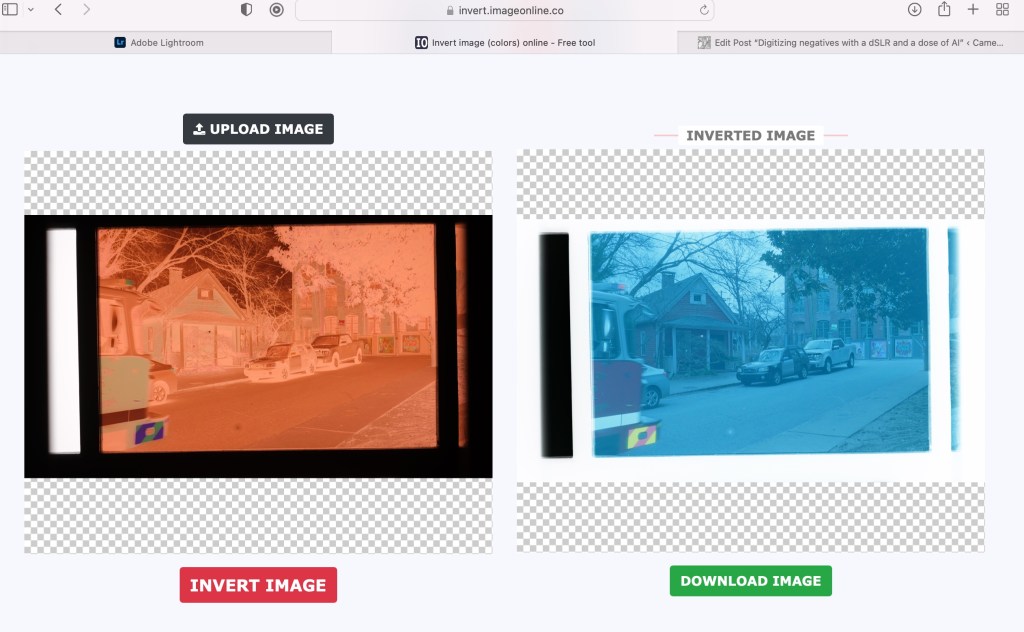

The obvious next step was to replace the flipping mirror and the optical viewfinder with an electronic viewfinder fed directly by the image sensor of the camera, and to improve the contrast detection autofocus to make it as reactive as a phase detection system, and available during the video shoot. Panasonic was the first to do it with the Lumix G2 in 2010. Almost everybody else would soon follow.

- The obvious advantage of a mirrorless ILC is that it can shoot indifferently photos and videos – the camera works exactly the same way. It’s a big plus for all the pros and content creators who have to deliver a full set of images (stills and videos) when they film weddings or corporate events.

- Mirrorless cameras, being deprived of the mirror box and of the optical viewfinder of a SLR can be made smaller, lighter, and probably cheaper because they are simpler mechanically.

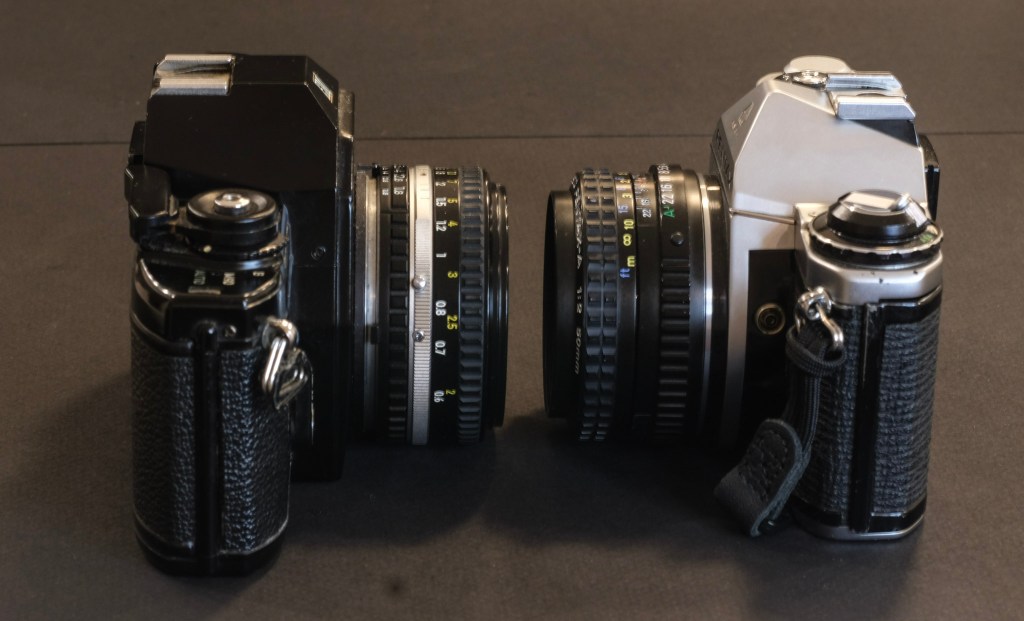

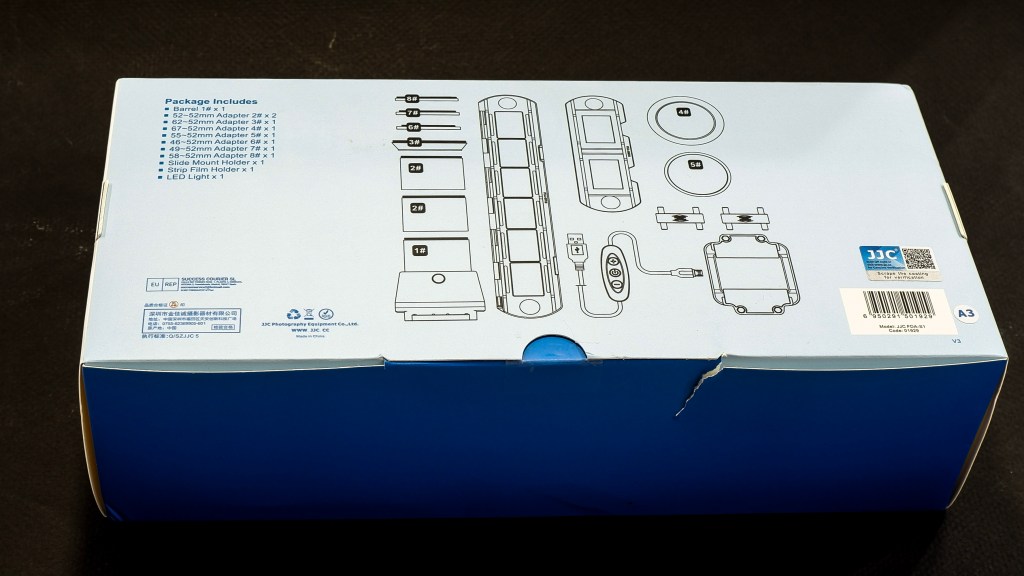

- The absence of a mirror box also reduces the lens flange distance, and lenses can be made shorter. Because there is no need for aperture pre-selection and full aperture transmission mechanisms, lens mount adapters are extremely simple to design and manufacture. Practically, almost any lens designed for an SLR or a dSLR can be physically mounted on a mirrorless camera.

Early mirrorless were handicapped by relatively poor electronic viewfinders (lacking definition, reactivity and dynamic range) and a limited battery life. Over time, mirrorless ILCs have made a lot of progress in those two areas – recent prosumer and pro ILCs have really impressive electronic viewfinders.

Electronic viewfinders show the image exactly as the image sensor is “seeing” it. If the viewfinder is good enough, it’s even possible to evaluate in real time the exposure of a scene – and play with the exposure compensation dial to adjust it: what you see is really what you’re going to get.

Advantages of recent dSLRs

The most recent dSLRs were launched between 2020 and 2021, and their capabilities are at best in line with what was the state of the art four to five years ago.

Those dSLRs offer bluetooth and Wifi, and are as easy to connect to a mobile device as modern ILCs.

They keep the traditional advantages of dSLRs: an optical viewfinder, and longer battery life, but as a consequence remain larger and heavier than ILCs.

The native support of lenses designed for the brand’s SLRs and DSLRs over the past decades looks like an advantage, but older lenses may only be partially compatible, and they may lack the resolution required to take advantage of recent image sensors.

As for newer lenses – they’re increasingly difficult to find now that the industry leaders have redirected their R&D and manufacturing efforts towards ILCs.

Switching back to a dSLR?

I wrote earlier I would not be judgmental, but I’m still struggling to understand why somebody would take a significant financial hit to move from a very recent, top of the line mirrorless camera system to a dSLR released eight years ago.

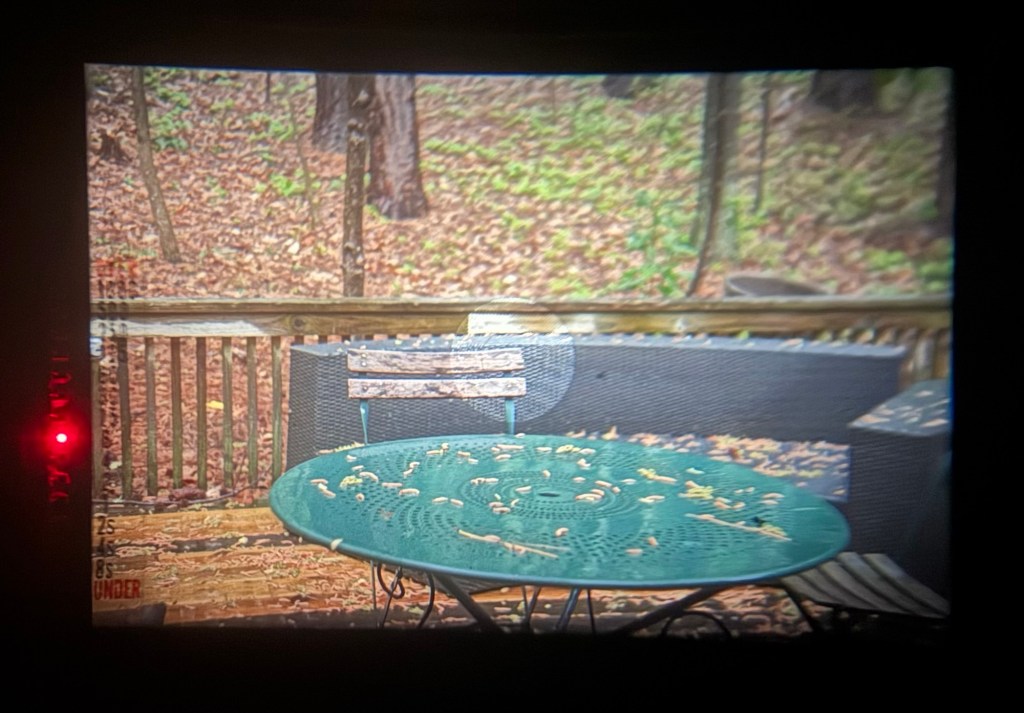

Even though I like shooting with dSLRs and older film cameras (they can be more pleasant to use than some mirrorless ILCs) I believe that using a recent mirrorless camera will increase my odds of capturing a technically good image (the artistic value is a totally different story).

Mirrorless cameras are more flexible and will be within their performance envelope in more situations. If the shooting opportunity is unique and I need to deliver – if only for my pride as an amateur photographer – I’ll bring my mirrorless kit with me.

As a lover of old gear – even digital – I’d like to offer a suggestion: very nice “prosumer” 16 or 20 Megapixel APS-C reflex cameras from the early 2010s can be found for $150; a “classic” like the Nikon d700 from 2008 (12 Megapixel, full frame) is more expensive, but not by that much if you pick a camera that has been used by professional photographers and has shot hundreds of thousands of pictures.

So, if you feel the dSLR hitch from time to time, my recommendation would be to keep your mirrorless system, and simply augment it with an old dSLR for the days when the call of nostalgia is too strong to resist.

More in CamerAgx about mirrorless and reflex digital cameras

When a recent mirrorless camera shines….