Until this year, the big Japanese camera makers seemed to have abandoned the “digital compact camera” market almost entirely, retreating to a few niche products such as the Sony RX100 or the OM System Tough TG, and leaving all the space of “casual photography” to smartphones.

The commercial success of a few of the remaining compact cameras (the current versions of Fujifilm X-100 and of the Canon G7x are almost always out of stock), and the prices reached on the second hand market by some high end compact cameras from the past decade are pushing the camera companies to reconsider their product strategy. Canon is widely rumored to be preparing a new range of compacts.

In the meantime, a few lines of cameras of the past decade – the Canon SX700, the Nikon S9000 and the Sony HX series in particular, are getting all the attention and are more expensive than ILCs of the same vintage on eBay.

Sony’s HX line of products

The H in HX stands for HyperZoom – the cameras of the series all have zooms that can reach at least an equivalent of 250mm on a full frame camera. Some of the HX models (the ones with three digits in their name) are shaped like a bridge camera and would not fit in a pocket, while the HX models with one or two digits (HX5 to HX99) are pocketable little bricks that could fit in the pocket of a coat.

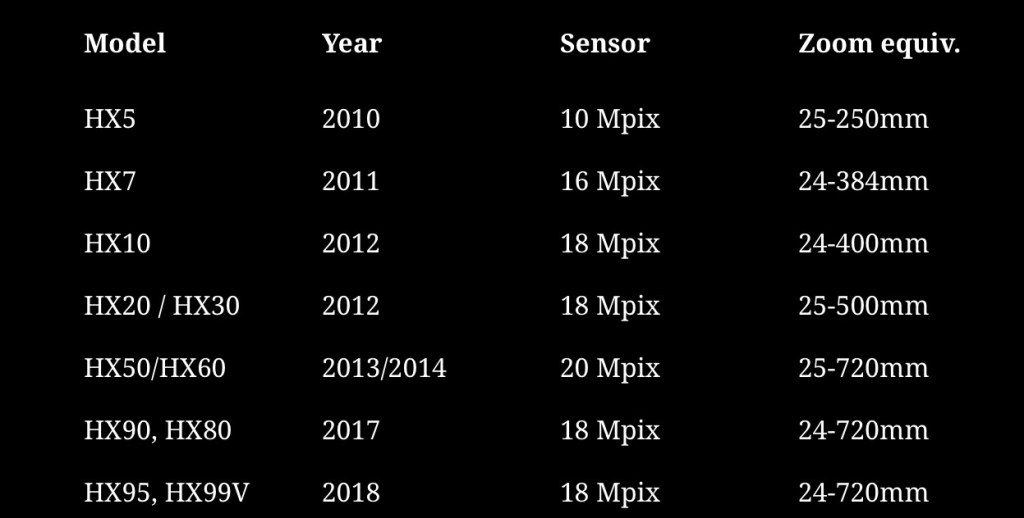

The HX pocketable models were developed across 4 generations.

HX5, HX7 and HX9 belong to the first one, with 10 and 16 megapixel image sensors and a reach limited to 384mm. The HX10, HX20 and HX30 form the second generation. They share a 18 mpixel sensor and are pretty close to one another – primarily differentiated by the reach of their zoom and the support of Wifi.

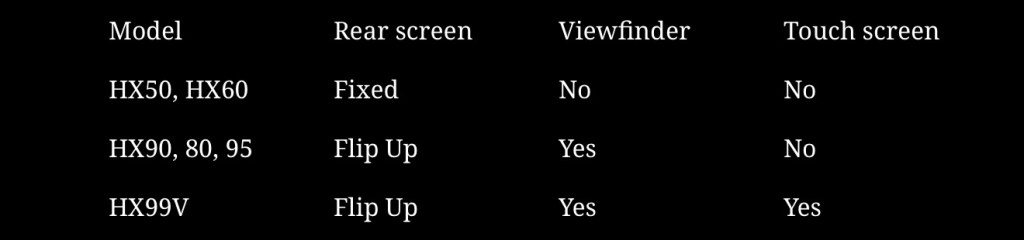

The HX50 and HX60 mark a significant evolution towards the high end, with a 20 Megapixel sensor, an accessory shoe, a bulkier body and longer zoom reach. They share a G series, 25-720 zoom. The main difference between the two models is that the HX60 has NFC in addition to Wifi, and is controlled through the new unified Sony menus.

The last four models (HX90, HX80, HX95 and HX99) all share a 18 mpix sensor and a smaller body with a telescopic viewfinder and a flip up screen. Their lens is a new, more compact, Zeiss labeled, 24-720 zoom. But they lose the accessory shoe of the previous generations and a few physical controls (like the exposure compensation control wheel). The differences between last four models are relatively minor. The HX80 is the simplest, while the HX99 has everything (a touch enabled rear display and a GPS, and it can save RAW files).

Lastly, all models whose name ends with a “V” have a GPS chip. The HX60, for instance, was available as a GPS-less HX60, while the HX60V had the GPS chip. Not all combinations were available in all geographies. The HX60, for instance, was not available in the UK or in the US, but the HX60V was.

The different models: a summary.

On paper, the most recent generation with its very compact body, its telescopic viewfinder, its Zeiss labeled lens and its flip up rear screen seems the most interesting. Recent models also benefit, generally, from image sensors and processing engines that produce better pictures (less prone to noise, and therefore more immune to the smearing caused by aggressive noise reduction algorithms). But models of that series are also the most sought after, and cost twice as much as a HX60 on the second hand market, at approx $500.

Shooting with the HX60

The HX60 is not exactly a pocketable camera, unless you wear a coat or an anorak with large pockets. And you will feel its weight – at 272g (9 1/2 ounces) it’s not light either, twice as heavy as a typical compact camera like the Sony W series or the Canon Powershot 170 IS. It does not give the impression of being fragile, but it’s not a rugged camera and its owner will feel compelled to carry it in a soft pouch.

It offers more physical controls than a typical point and shoot and elaborate menus (inherited from Sony’s big mirrorless cameras) which, coupled with the rather succinct documentation, could make it intimidating for beginners.

I left it in Program (“P”) mode most of the time; there are also a “Superior Auto Mode” and an “Intelligent Auto Mode” that detect the scene for you and adjust the settings accordingly – simply adjusting the exposure with the correction dial when needed. I’m not sure there is any benefit in leaving the full automatic modes for Aperture or Shutter Speed priority modes – the largest aperture varies between f/3.5 and f/6.3, and the smallest aperture is always f/8 – your options are limited. And even if a shutter speed of 1/1600 sec is proposed, selecting it it will force the camera into very high ISO territory – to the detriment of image quality.

Compared to the screen of a modern smartphone, the display of the HX60 is not very bright – you have to set it to +2 to be able to compose somehow comfortably when shooting outside. It takes a toll on the battery life, which is limited to one or two hundred pictures in the real life.

The HX60 supports WiFi connections to a smartphone or a tablet using Sony’s current “Imaging Edge Mobile” application. Transferring photos to the mobile device from the camera is not 100% intuitive, but with a bit of trial and error, it can be achieved.

Image quality

Image quality is surprisingly good for a camera with such a small sensor – as long as the sensitivity remains under 800 ISO. Fortunatelly, if you leave it in auto mode, the camera is programmed to operate when possible at very slow shutter speeds (and in the 80 to 250 ISO range) and thanks to its very efficient optical image stabilization system, it still delivers images free of motion blur at 1/20sec.

Images shot at 1600 ISO or above are best viewed on the small screen of a smartphone, as the noise and the image smearing resulting from the noise reduction algorithm take their toll. The 18 Mpixel sensor of the cameras of the following generation (HX80 and above) is supposed to perform better in those situations, but I had used a Sony WX350 (equipped with the same 18 Mpixel sensor) for night shots in Las Vegas a long time ago and even if the neons looked fantastic, noise severely impacted the poorly lit areas. If there is an improvement, it’s marginal.

As a conclusion

What distinguishes this camera is the very long reach of its zoom. Shooting with wide angle lenses is more natural for me, and with my “normal” cameras most of my pictures are taken at a focal length located somewhere between 28 and 40mm (full frame equivalent). Shooting with a small camera that can reach a focal length of 720mm is a new experience for me, and a sort of eye opener. You look at the world differently when you know you can isolate details far, far away.

The Sony HX60 is a very efficient little camera, using its elaborate technology (a really impressive image stabilization system in particular) to overcome the limitations of its small sensor and deliver very nice pictures. It’s not exactly pocketable and without being fragile, it has to be treated like a small “serious” camera rather than an always available note taker that you will throw in a handbag with your car keys.

Because the camera manufacturers have more or less abandoned the “elaborate, small sensor” compact market, this Cybershot from 2014 is very close to representing the “state of the art” when it comes to “travel zoom” compacts. The HX60 is not for everybody, but if you like long, long zooms in a 270g camera, this one is for you.

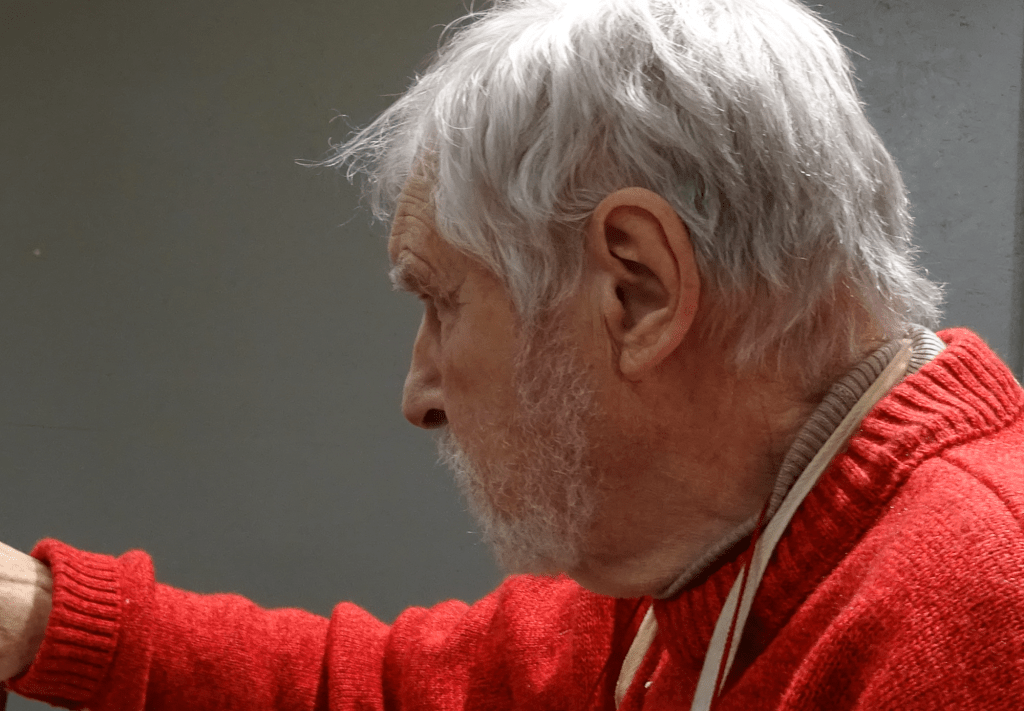

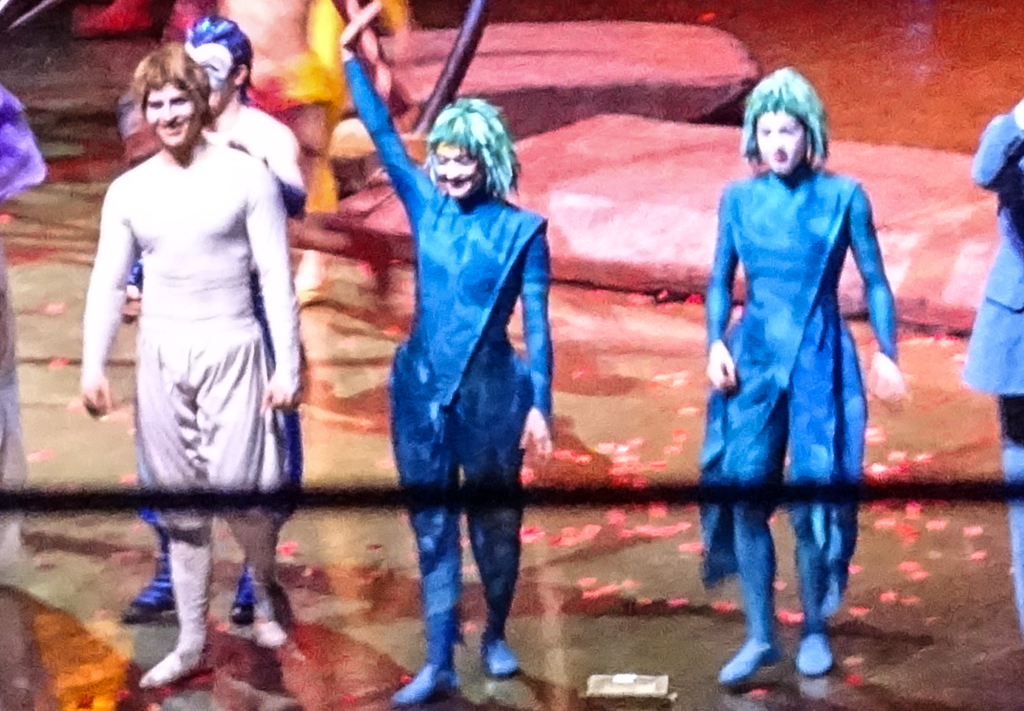

This camera belonged to my late father in law, Eric, who passed away recently. In his late years, he was more interested in painting, but he still knew how to use a camera. He shot most of the pictures posted below. They show what a person with a good eye but no particular interest for photography can get out of a HX60.

More pictures taken with the HX60 in my Flickr album