When kids take a photography class in high school, the teachers typically recommend cameras like the Pentax K1000. If you Google “best learner camera for film photography”, most of the sites making the top of the list will recommend the Pentax K1000 (again), or cameras such as the Canon AE-1 (often), the Nikon FM, the Minolta X-700 or the Olympus OM family. All are manual focus cameras, all were launched in the seventies or in the early eighties, and most of them only offer semi-automatic (some people call it “manual”) exposure.

James Toccio in his blog “Casual Photophile” is almost the only one to make the case that newcomers to film photography should start with a camera from the mid nineties, because with its multi-mode auto-exposure and reliable auto-focus system, it’s more similar to the current digital cameras, and will yield much better results for an untrained photographer than a semi-auto/manual focus camera from the seventies (in: Casual Photophile – How to cheat at Film Photography)

James may have a point here. And if you look for a reliable, auto-focus multi-mode SLR with great performance and a large supply of lenses, the Nikon N90s is a very good choice.

Unfortunately, if the value of a camera on the second hand market is any indication, most buyers disagree: very good enthusiast-oriented auto-focus SLRs from the mid-nineties such as the N90s or the Minolta Maxxum 9xi seldom sell for more than $25.00, in the same ball park as the very primitive K1000, with more amateur-oriented auto-focus SLRs (such as Minolta’s Maxxum 400si or Nikon’s N6006) struggling to reach the $10.00 mark.

The Nikon N90s

Nikon joined the auto-focus market shortly after Minolta launched the Maxxum 7000. Its first auto-focus SLRs were slow to focus – even the flagship F4, but it did not matter much at the beginning, at least not until Canon launched the EOS-1, and showed what a good auto-focus camera should be able to do. From there on, Nikon had to play catch-up. It took them almost 10 years to do so (with the F5 & F100 bodies and the motorized AF-S lenses), and in the meantime, Nikon’s cherished pros kept on defecting to Canon in droves.

Launched in 1992, the N90 (named F90 in the rest of the world) was Nikon’s first real response to the EOS series. Officially, the N90 was designed for committed enthusiasts. But scores of pros also bought the N90, because it had the best auto-focus system Nikon could provide at the time. The “N90s” aka “F90X” that rapidly followed was a level of performance above the N90 (improved auto-focus and weather sealing), with a mission to retain the pros who had fallen in love with the Canon EOS system until the launch of the F5.

-

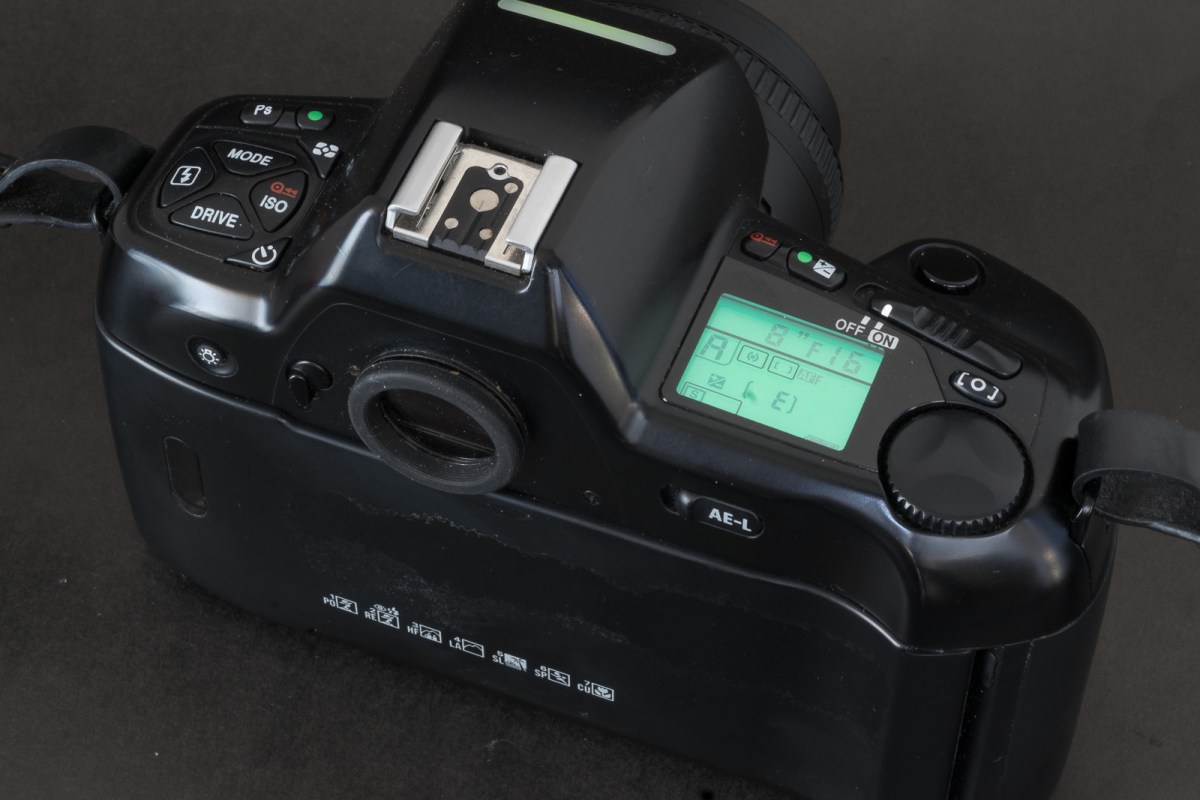

Size, weight, features and ergonomics

The N90s is a typical auto-focus SLR of the mid-nineties – with a black polycarbonate shell and high levels of automation: auto-exposure with the conventional Aperture Priority, Shutter priority, Program and Manual (understand semi-auto) modes, Matrix, Weighted average and spot metering, and motorized film loading and rewind. Compared to its lesser amateur oriented siblings, the N90 has no built-in flash, but a better shutter (1/8000 sec and flash sync at 1/250), a better viewfinder and runs on AA batteries (instead of the harder to find and more expensive lithium batteries).

Apart from the build quality and the use of Nikon F lenses, the N90S has very little in common with the previous generation of “enthusiast” and “pro” cameras, the FE2 and the F3. While not as bulky as a modern full frame dSLRs (like the D810), N90s is larger than the FE2, as heavy as the F3, and very close to the D7500 in its dimensions and weight.

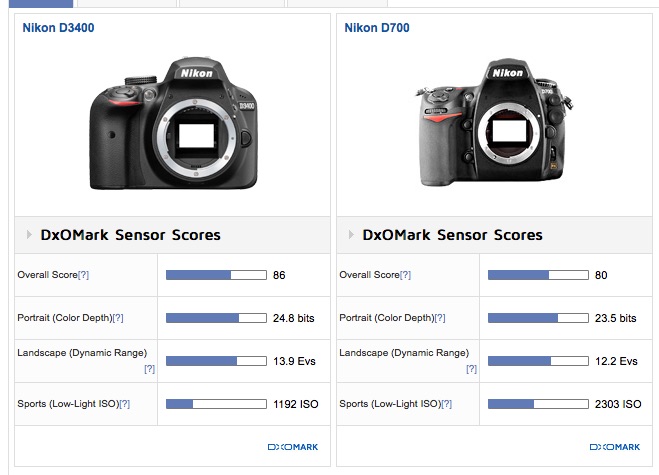

| Nikon Film Cameras | Nikon dSLRs | ||||

| FE2 | F3 | N90/N90s | D7500 | D810 | |

| 35mm film | 35mm film | 35mm film | Digital – APS-C (DX) | Digital (full frame – FX) | |

| weight (g) | 550g | 760g | 755g | 640g | 980g |

| height (mm) | 90mm | 101mm | 106mm | 104mm | 123mm |

| width (mm) | 142mm | 148mm | 154mm | 136mm | 146mm |

- Viewfinder

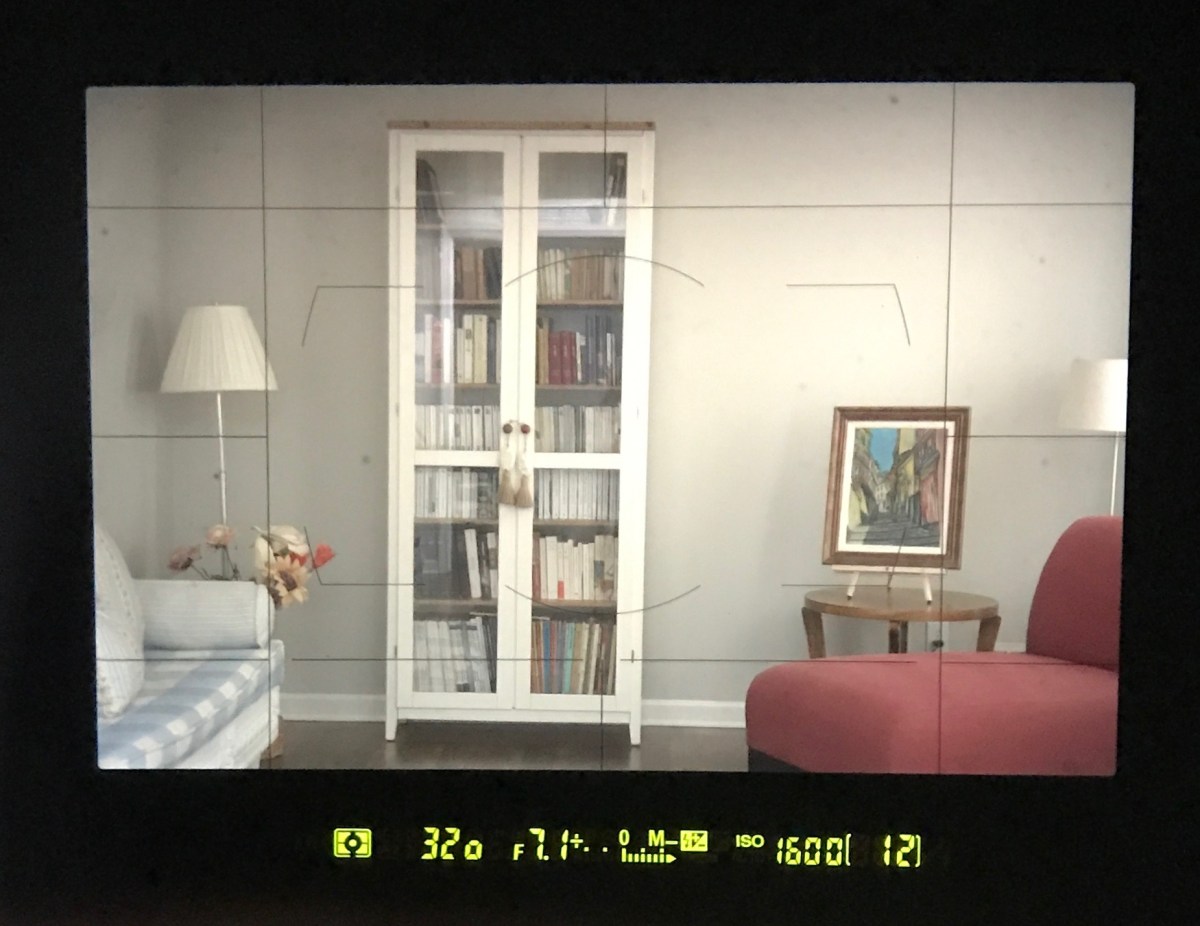

In my opinion, the long eye point viewfinder of the N90 is one of the two reasons to prefer the camera to a FE2, the other one being its very accurate matrix metering. With a magnification of 0.78, a 19mm eyepoint and 92% coverage, it’s a good compromise between magnification (the image is large enough) and the eye point distance (at 19mm, it’s confortable for photographers wearing glasses).

It’s not as good as the high-point viewfinder of the F3, but much wider than the viewfinder of a conventional SLR such as the FE2 – and of course than the narrow viewfinder of APS-C dSLRs. It’s also very luminous, not as much as a modern full frame dSLR (such as a d700), but much more than its Minolta competitors of the nineties. All the necessary information is grouped on a green LCD display at the bottom of the screen. The only significant difference with modern Nikon cameras (and with Minolta cameras from the nineties) is that there is no LCD overlay to show information (such as the area of the image chosen by the auto-focus system) – considering there is only one central autofocus area, it’s not much of an issue.

- Shutter, metering and auto-focus system:

The shutter is still at the state of the art (1/8000 sec and flash sync at 1/250). Nikon’s matrix metering was considered the best in the nineties, and it’s still very good. You can trust it most of the time. The auto-focus (a single sensor, in the middle of the screen) is reactive, accurate, and works well in low light situations. - Lens selection and accessories compatibility

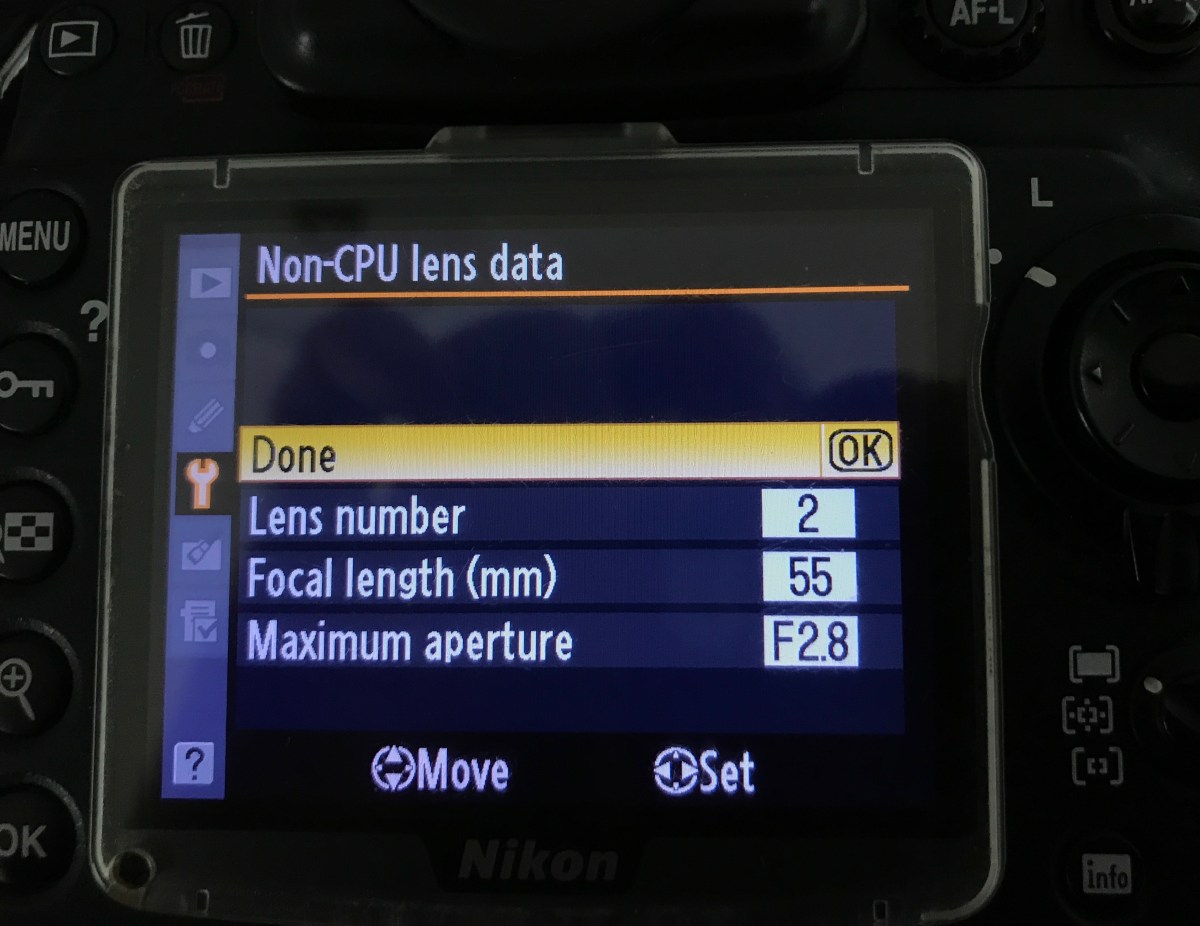

Designed for Nikon’s “screw drive” AF lenses (Nikon AF and AF-D lenses), the N90 also works with AI and AI-S lenses – basically, anything sold by Nikon after 1977. The camera can also focus with modern Nikon AF-S lenses (the ones with the focus motor in the lens), and works in Program and Shutter Priority modes with lenses devoid of an aperture ring (most of the current Nikon AF-S lenses). It can’t work with them in Aperture preferred or Manual (semi-auto) mode, because there is no way for the photographer to directly set the aperture. It is not compatible with pre-AI lenses (unless they’ve been converted to AI, of course) and can not take advantage of the vibration reduction (VR) function of the recent lenses.

The N90 was part of Nikon’s line of Enthusiast and Pro cameras, and many accessories (the remote control systems, for instance) are still inter compatible with Nikon’s current Enthusiast and Pro dSLRs. The flash systems are downwards compatible (you can use a recent Nikon flash on the N90, but the opposite is not true).

- Reliability

The N90’s polycarbonate film door was initially covered with a sort of mat soft skin which has a tendency to peel. Rubbing alcohol will take care of it, and will leave you with a shiny, naked camera. Apart from this somehow minor issue, it is a very solid and reliable camera.

- Battery

The N90 uses four AA batteries, which are cheap and easy to find, and do not seem to be depleting too fast. - Cost and availability

I don’t have production figures for the N90. But the camera was a sales success, had a long production run, and has withstood the test of time pretty well. It is still easy to find. Supply apparently widely exceeds demand, and the prices a incredibly low for a camera of such quality (if you’re lucky, $25.00 buys a good one).

Conclusion: why is this camera so unloved?

Objectively, the N90s is a very good film camera. It has a great viewfinder, you can trust its metering system and its auto-focus. It is solid, reliable, and runs on cheap AA batteries. It’s designed to be used as an automatic camera, but lets you operate with manual focus lenses or in semi-auto exposure mode if you so wish. Why is it so unloved?

Because it’s a tweener. It’s far too modern for some, and not enough for others.

Its predecessor in the eighties, the FE2 and the F3, are simple cameras, with a single auto-exposure mode, average weighted metering and no integrated motor. They offer the minimum a photographer needs, and a few goodies at the top of that (shutter speed and aperture values displayed in the viewfinder, depth of field preview, exposure memorization). Nothing more.

The FE2 and the F3 are the cameras that a photographer will look for when he wants to work on his technical skills, as a pianist would do with his scales.

They will also appeal to photographers who believe that using a simple tool and following the deliberate process it imposes will help them create more authentic, more personal pictures.

For those photographers, the N90 is already a modern (understand feature bloated) electronic camera. It is not too dissimilar in terms of ergonomics, commands, auto-exposure and auto-focus performance to a recent entry level dSLR – except that you shoot with real film instead of relying on a digital sensor and on film simulation algorithms. The technical difficulties of photography are to a large extent masked: you can shoot for a whole day in the programmed auto exposure mode, with matrix metering and auto-focus, simply concentrate on the composition of the pictures, and still get mostly good results.

But the N90’s successor – the Nikon F100 – is even better at producing technically perfect pictures with little human intervention. Manufactured from 1999 to 2006, it is closer technically to the high-end dSLRs that Nikon is selling today (general organization of the commands, meter and auto-focus performance, full support of AF-S and VR lenses). The F100 is a better choice for photographers shooting not only with film but also with a full frame Nikon dSLR – they can use the same lenses and rely on their muscle memory because the commands are so similar between the F100 and a high end Nikon dSLR.

It relegates the N90S to a narrow niche of film photographers who want the convenience of auto-focus and automatic exposure, the build quality and the viewfinder of a pro-camera, without having to pay to the roof for the ultimate film SLR.

More about the Nikon N90s

Thom Hogan’s review : http://www.bythom.com/n90.htm

The Casual Photophile’s review: https://www.casualphotophile.com/2017/10/13/nikon-n90s-camera-review/