Cameras designed and manufactured before 1975 very often use coin shaped Mercury Oxide batteries to power the CdS cell in charge of metering – the most common being the PX625 aka PX625 / PX13 / MR9 Mercury Cell.

The chemistry of those 1.35 V. batteries is based on mercury oxide. The sale of mercury batteries was banned in 1996 because of their toxicity and environmental unfriendliness, and, unfortunately for the owners of camera of the early 70s, there is no perfect substitute. For all of their drawbacks, mercury oxide batteries had two big advantages – they delivered a constant 1.35v tension across their lifespan, and if not used, they kept their charge for a very long time (at least 10 years).

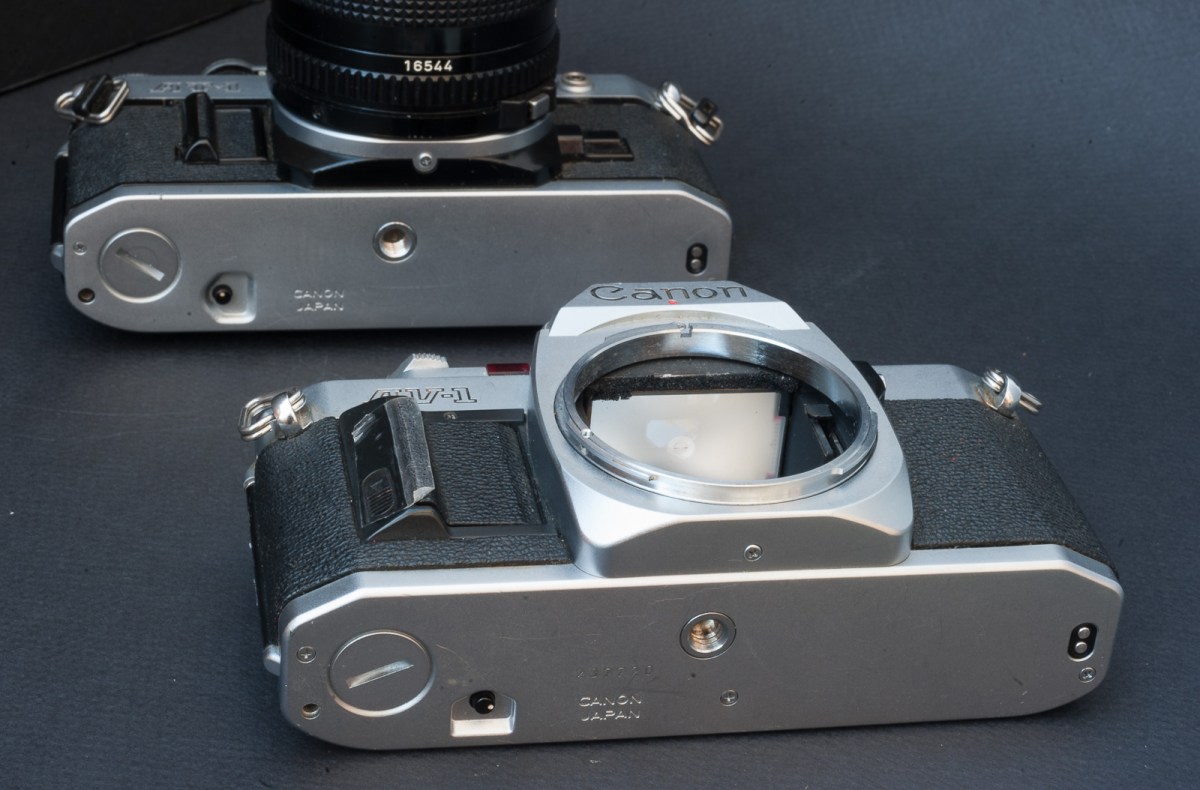

The most common cameras using the PX625 battery were launched between 1970 and 1975: Pentax Spotmatic F, Olympus OM-1, Leica CL, Leica M5, Nikkormat FTn, Canon FTb and Canonet GIII QL, … . The battery looks like 3 coins of different diameters stacked above one another, and is rather large and thick (Diameter: 15.6 mm. Height: 5.95 mm).

Older cameras (like the original Pentax Spotmatic, for instance) use a smaller button (or pill) shaped Mercury Oxide battery, and more recent models (practically any camera designed and launched after 1975) use silver oxide or lithium batteries in many shapes and forms.

Possible Replacement:

- alcaline – (LR9 or V625U) – this battery has one big advantage – it’s the same shape and dimensions as the PX625 – but it has two limitations – its nominal voltage is higher at 1.5v; and it loses voltage progressively, which makes it unfit to provide power to the meter of a camera, unless some voltage compensation circuit is built into the camera. The meter of some cameras will not work at all (Leica CL), and for most other cameras the metering will be unreliable.

- Silver oxide – it delivers a constant voltage across its lifespan, and can last for a few years when not in use. But unfortunately, its voltage is significantly higher at 1.55v, which again will promise unreliable metering results unless the camera or the battery container itself is designed with a voltage compensation circuit. There are three options:

- the S625PX – I believe it’s been discontinued – it had the same shape as the mercury PX625 battery, but delivered 1.55v – it will only work as a substitute for a PX625 if the camera has a built-in voltage compensation circuit,

- a silver oxide “386” battery (a “button” cell), inserted into a adapter with its miniaturized voltage reduction circuit – the adapter is rather expensive ($35 to $40.00). It would be an ideal solution for photographers willing to use the camera regularly- but there are fakes on Amazon (products without the voltage reduction circuit presented has products with). Only buy from a seller you trust.

- a Silver oxide 386 battery (a “button” cell), inserted into a adapter without any voltage reduction circuit – some of the “adapters” are as simple as a rubber gasket – again, it will only work if the camera has a built in voltage compensation circuit.

- Zinc-Air batteries have three big advantages – they’re used for hearing aids and are sold in every drugstore/pharmacy in the US, they release the same voltage as mercury batteries; and the voltage remains constant over the life of the battery;

You can buy a Zinc-Air button cell and insert it in the battery compartment of the camera (it may work with some cameras). A more reliable solution is to buy a PX625 substitute assembled by a few vendors who integrate third party zinc-air cells in a container shaped as the original PX625. The best know product is the so called “WEIN Cell” but there are alternatives available on Amazon.WEIN cells are packaged in individual blisters, and are cleanly assembled. They fit physically in all the cameras I tested. When the WEIN cells were more expensive than they are now, I had bought “compatible” cells from Exell on Amazon – they worked, but didn’t look as nicely finished and assembled as the WEIN cells – and could not fit in the battery compartment of a Leica CL. Currently, the “compatible” cells are more expensive than the original WEIN. So why bother?A Zinc-Air batteries are powered by oxidizing zinc with oxygen from the air. Therefore, the shell of the battery has small vents that let the air enter the battery. Batteries are stored and shipped with a removable membrane that “seals” the vents and deprive the battery from the air’s oxygen. To activate the battery, you remove the membrane – but once the zinc-air reaction has started, the life of battery is limited to a few weeks at best. Some people remove the battery from the camera after each photo shoot and reseal them, but I’m not convinced that it really helps extend the life of the battery.

(source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zinc%E2%80%93air_battery)

As a conclusion…

The WEIN cell worked on every camera I tested. It’s a relatively expensive solution if you want to use cameras designed for Mercury Batteries on a daily basis: because of the short life of the battery once you’ve activated it, you will have consumed a significant quantity of batteries by the end of the year.

If you’re absolutely determined to use a Leica CL or a Leica M5, I’m afraid there is no real substitute to WEIN cells. That being said you could also shoot with a Minolta CLE or a Leica M6, the experience would not be very different, and those cameras rely on Silver Oxide batteries (*). Up to you.

(*) – I did not find a more modern substitute to the Canonet using silver oxide battery. The models that immediately followed (the Canon A35F and A35 Datelux) were sold well into the eighties, and still used a mercury battery. Cameras launched after the A35 are motorized autofocus compact cameras – a totally different experience. If you like cameras in the style of the Canonet, Zinc-air cells are in your future.