In a previous post, I was debating whether it made sense for me to adopt Lightroom for Mobile and rebuild my workflow and photo cataloging process with it – and the answer was mostly Yes. I had concerns about the inability to perform bulk tagging over an album. I have not found a perfect solution – tags can be copied and pasted from one picture to another one, but as far as I can see, you have to paste the tags on every picture individually. Not ideal.

The big unknown was whether I should also migrate my old Lightroom libraries to Adobe Cloud as well. I checked – I have 30,000 photos on my network storage (a mix of proprietary RAW files from Nikon, DNG files and JPEGs). But they only consume 300 GB on the NAS (that’s an average of 10MBytes per picture if you do the math), and it’s likely that nearly half of those images are duplicates (images were generally copied from the memory cards and saved as Nikon proprietary RAW files, then converted to Adobe’s DNG format and saved again). And I tend to keep every image, good or bad, when most pictures should have been culled a long time ago. So, maybe less than 100 GB of keepers. Adobe Cloud storage fees will not send me to the poor house.

Originally, I thought I would simply be copying my old Lightroom 6 catalog file to the Adobe Cloud, and that Adobe would do the rest. It’s simply not the case.

Firstly, not everything is migrated: the history of the edits, the folder structure, the books, slideshows, and smart collections and a few other things don’t make the trip to the cloud (I assume they remain available on Lightroom Classic if you keep licensing it after the migration to Lightroom, but I could not validate this statement for the reason exposed in my second point). For all practical purposes, it looks like Adobe Lightroom Classic and Lightroom (in the Cloud) are two significantly different products – and that a lot is lost during the migration.

Secondly, Lightroom catalogs and files can’t be uploaded to the cloud by Lightroom 6. The migration to Adobe’s cloud can only be performed from a recent version of Lightroom Classic, and upgrading from LR6 to LR Classic is a necessary first step. You can get a 7 day trial version of Classic, so it’s not directly about money. The problem is that Classic only runs on a recent PC or Mac (Windows 10 or better, MacOS 13.1 or better) – and my Mac is an antique by their standards – it won’t run LR Classic. There are other constraints I did not even explore like finding more local storage for the Lightroom cache (with Lightroom, images are stored permanently and at full size in the cloud and replicated to a cache on the PC or the Mac only when they are needed), because I was not going to upgrade to a new Mac just to be able to migrate my Lightroom catalogs.

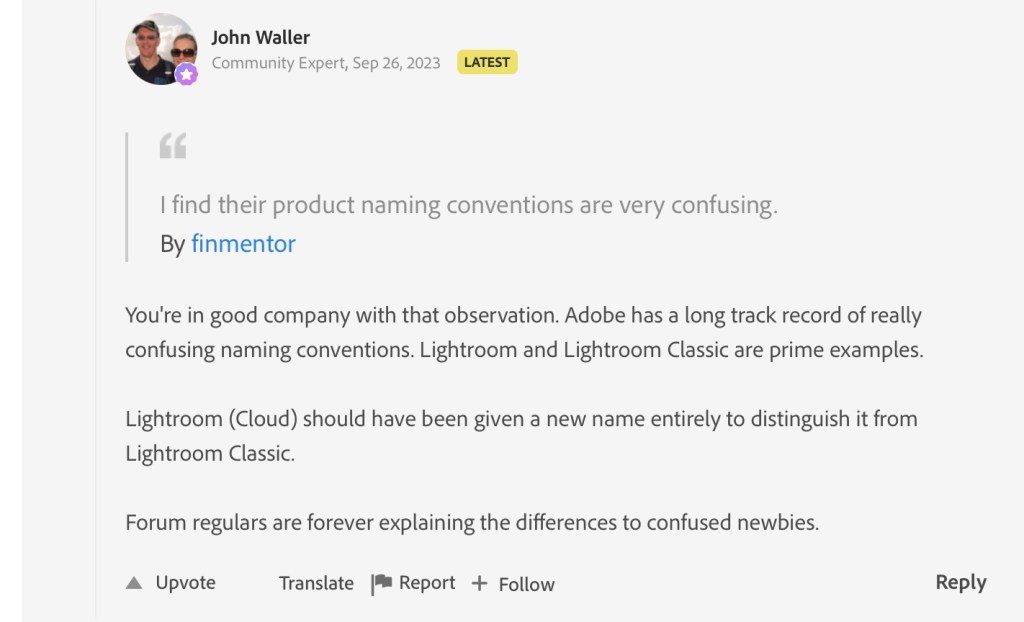

Thirdly, if it sounds clear as mud to you, you’ll be comforted in knowing you’re not alone – from Adobe’s Community Support:

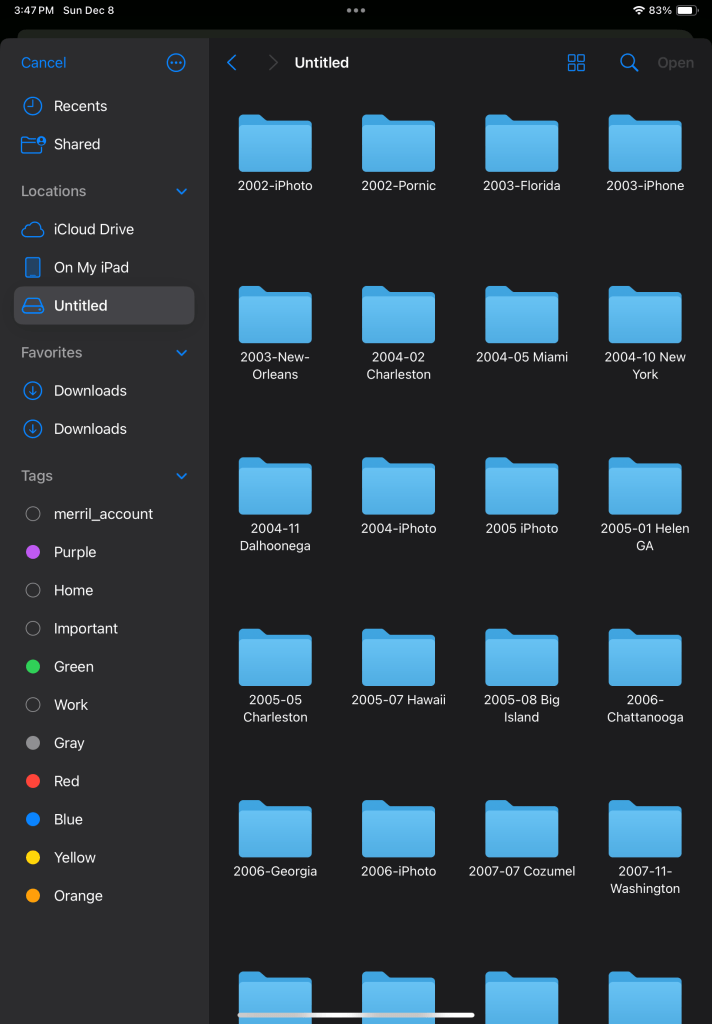

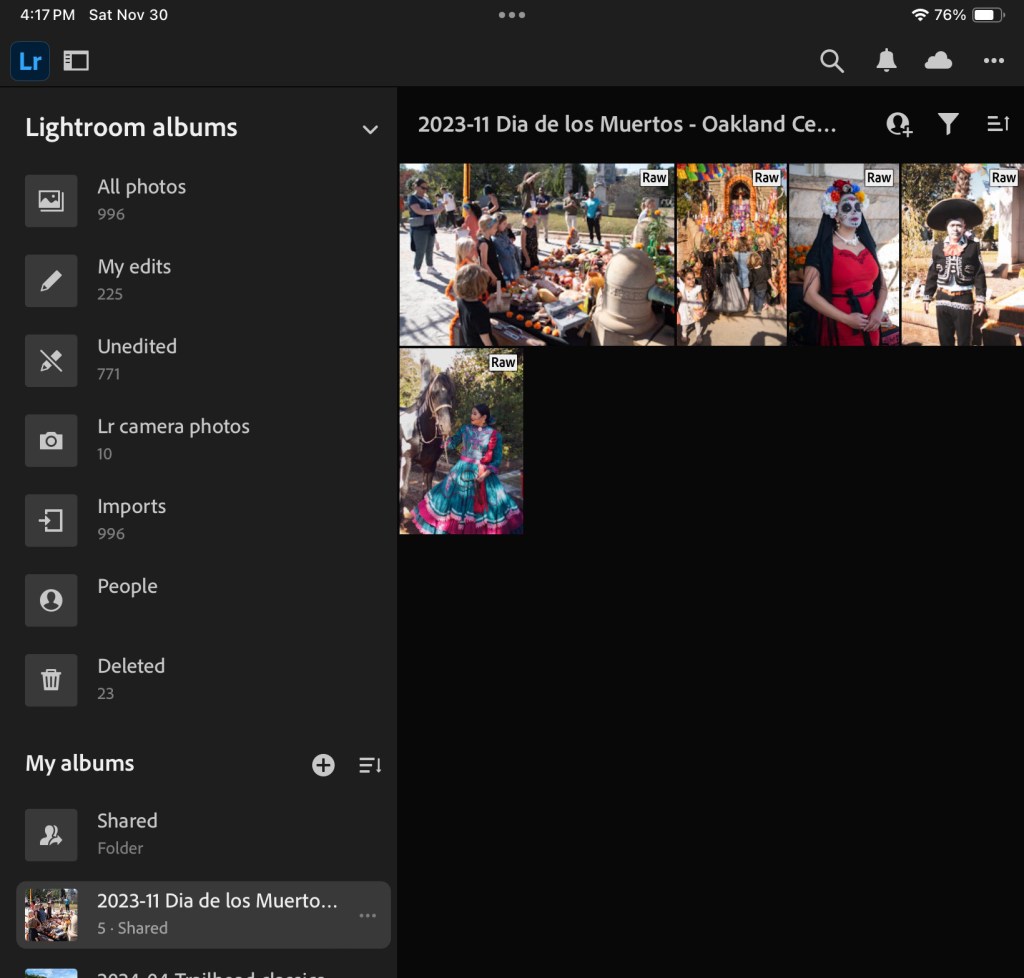

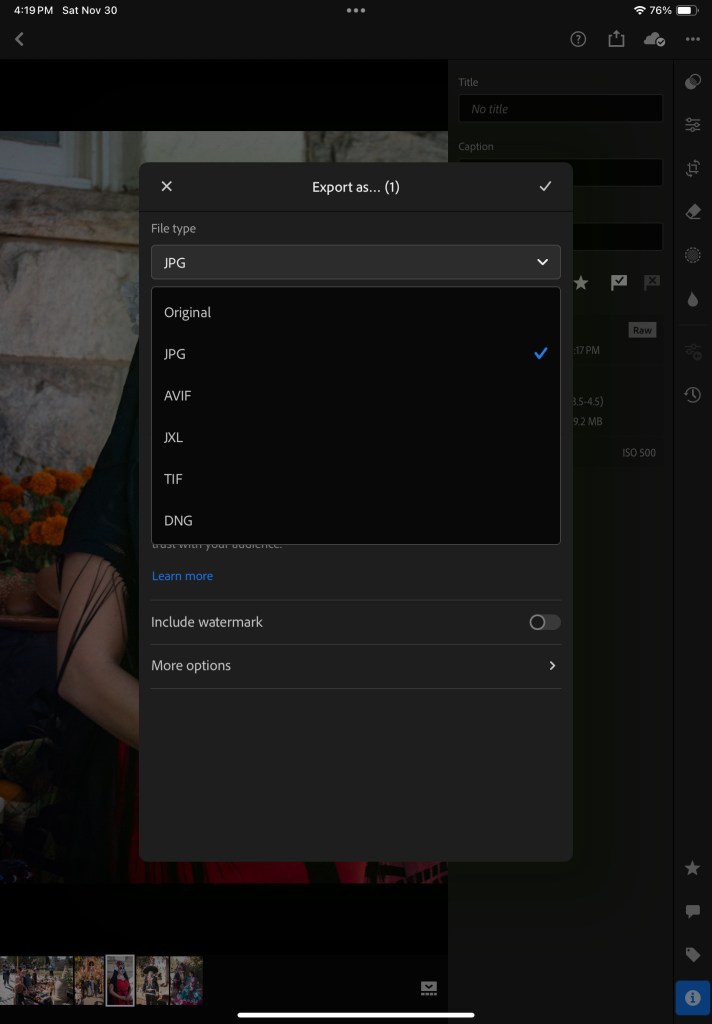

So, considering all of the above, I decided NOT to migrate my Lightroom catalog to Adobe’s cloud. Instead I’ll export already developed JPEGS from Lightroom 6 to Lightroom Mobile, collection by collection.

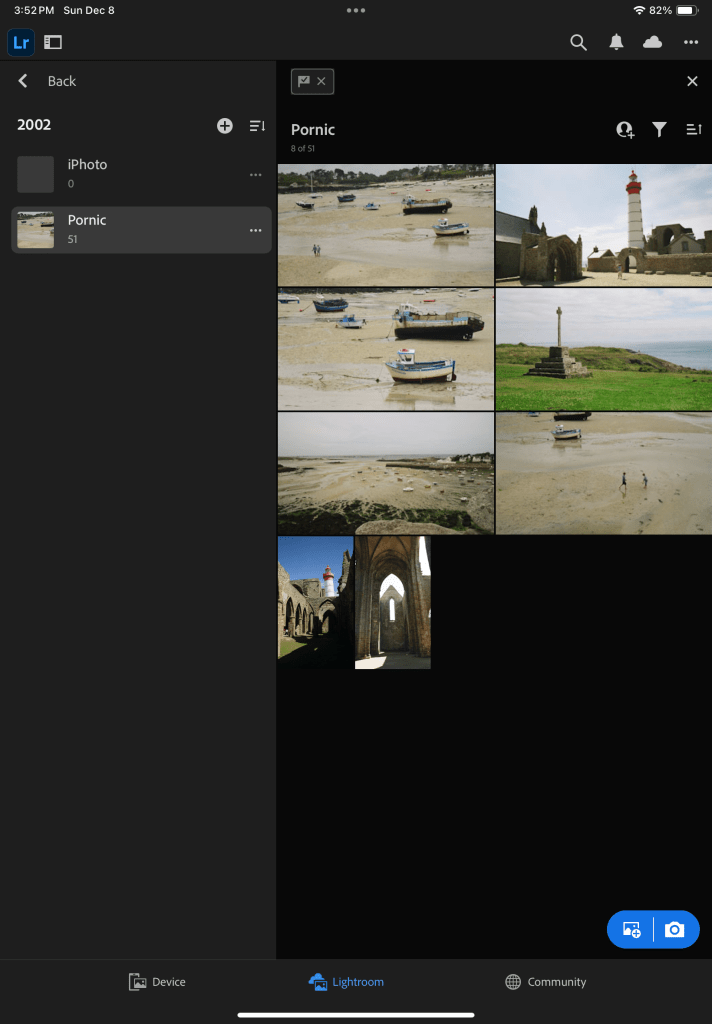

I don’t think I’ll miss much. Because so much is lost during the catalog migration, just exporting the Jpegs is going to be almost as good. I’ve been using Lightroom Mobile for a while now, and anything I’ve shot in the last 24 months and that I may need to edit again has already been uploaded to Adobe’s cloud. Anything older than two years was culled and processed in Lightroom 6 a few days after it was shot, and it’s unlikely I’ll need to go back to the original RAW or DNG files and process them again. Keeping the good pictures as JPEGs in Lightroom Mobile makes me laptop free, with images always accessible, easy to consume and share. And if I ever need to re-process a 15 year old RAW file, my Lightroom Folders and Albums are mimicking the folder structure I have on the NAS, and finding the image I need will be easy.

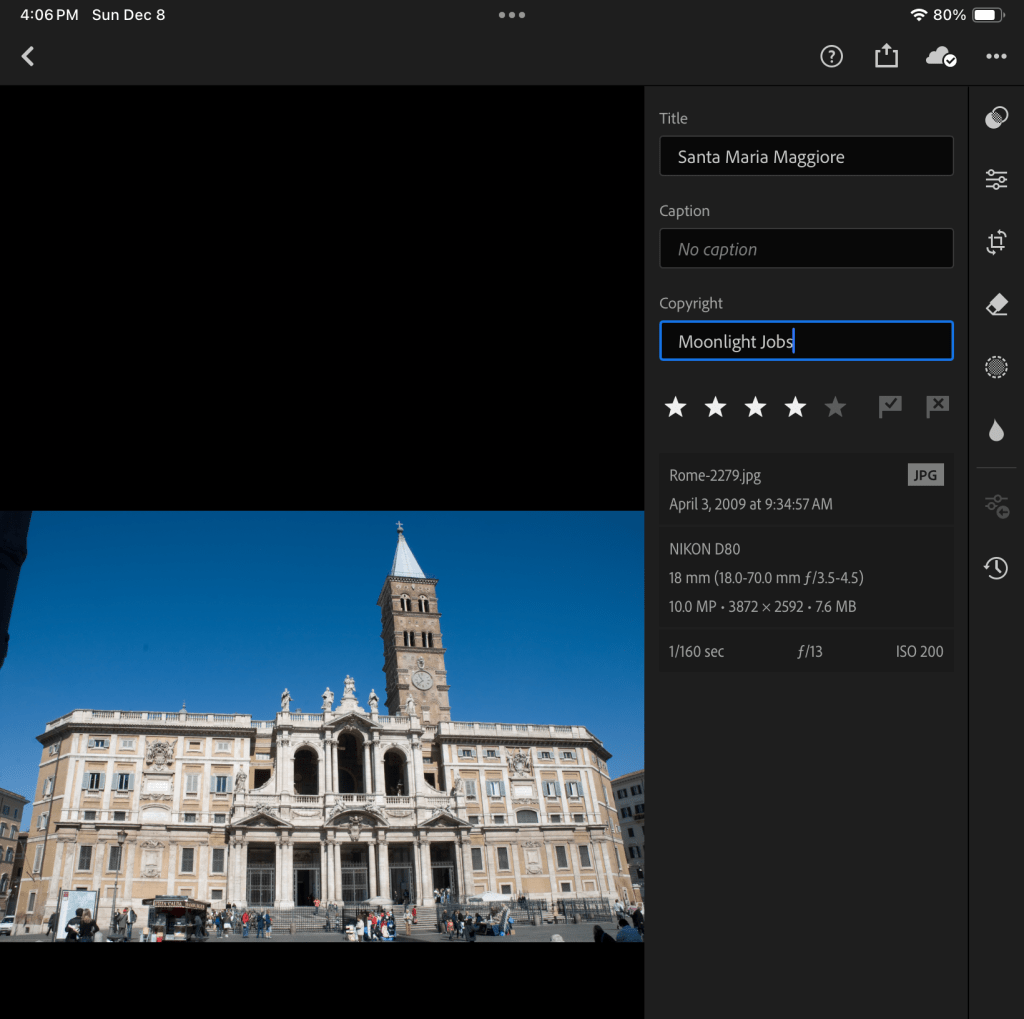

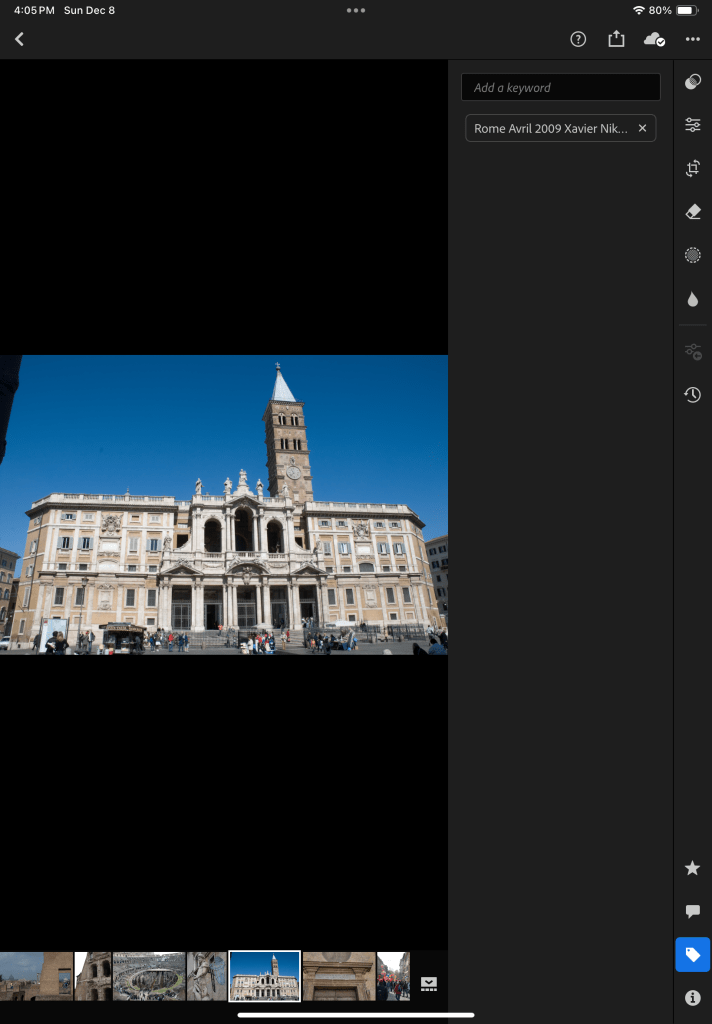

One thing I took great care of testing was how the metadata associated with each picture was migrated to Lightroom Mobile.

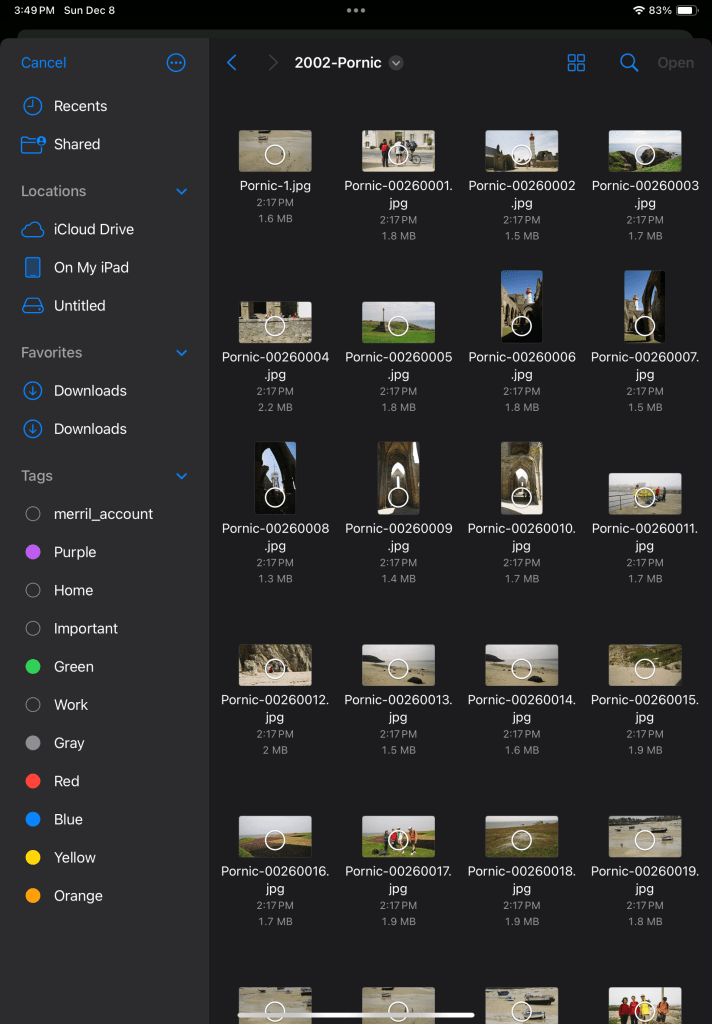

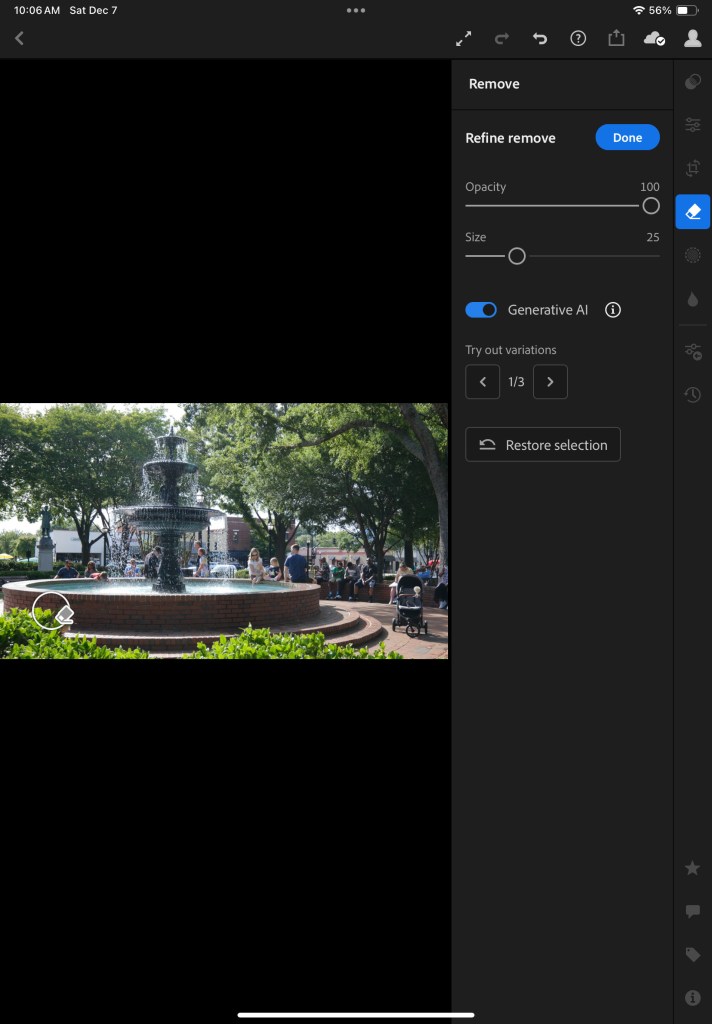

I exported the images as JPEGs, and they reflect the last changes made to the image in Lightroom 6 – if the original image was cropped, its sliders moved left and right, I won’t know it because the log of the edits is not incorporated in the JPEG that Lightroom generates. In other words, the images will be exported in their most recent state without their history, and no roll back of the settings will be possible.

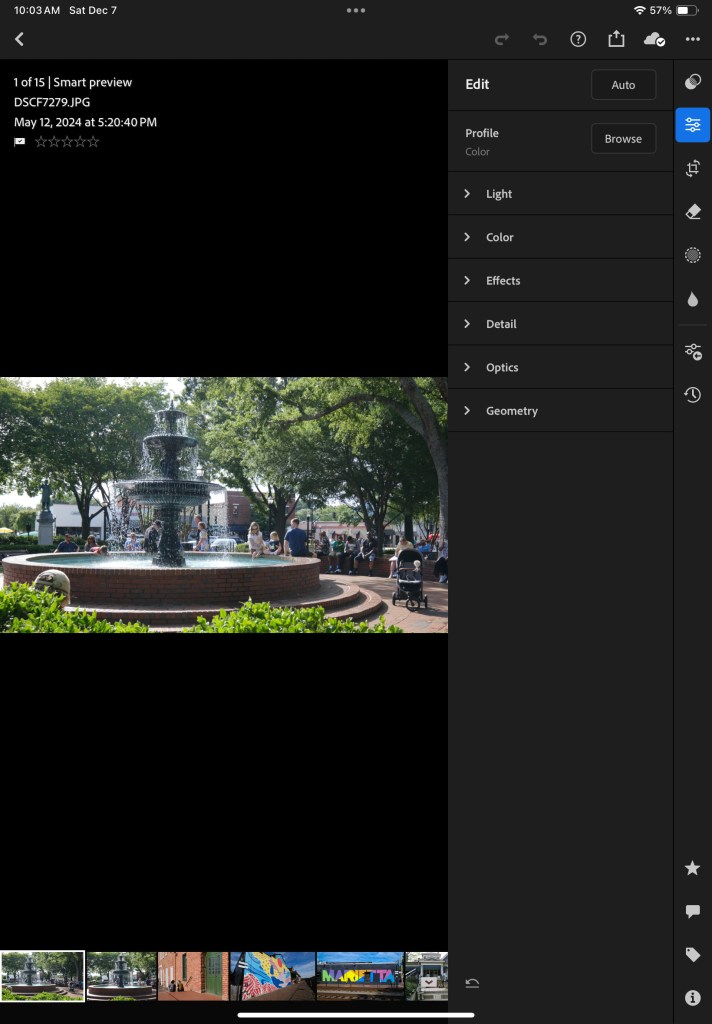

On the other hand, anything else is incorporated into the JPEG image – the metadata recorded originally by the camera or the film scanner, of course, but also the title, captions, keywords and even the flags and the stars added by the photographer and associated with the image in Lightroom’s catalog.

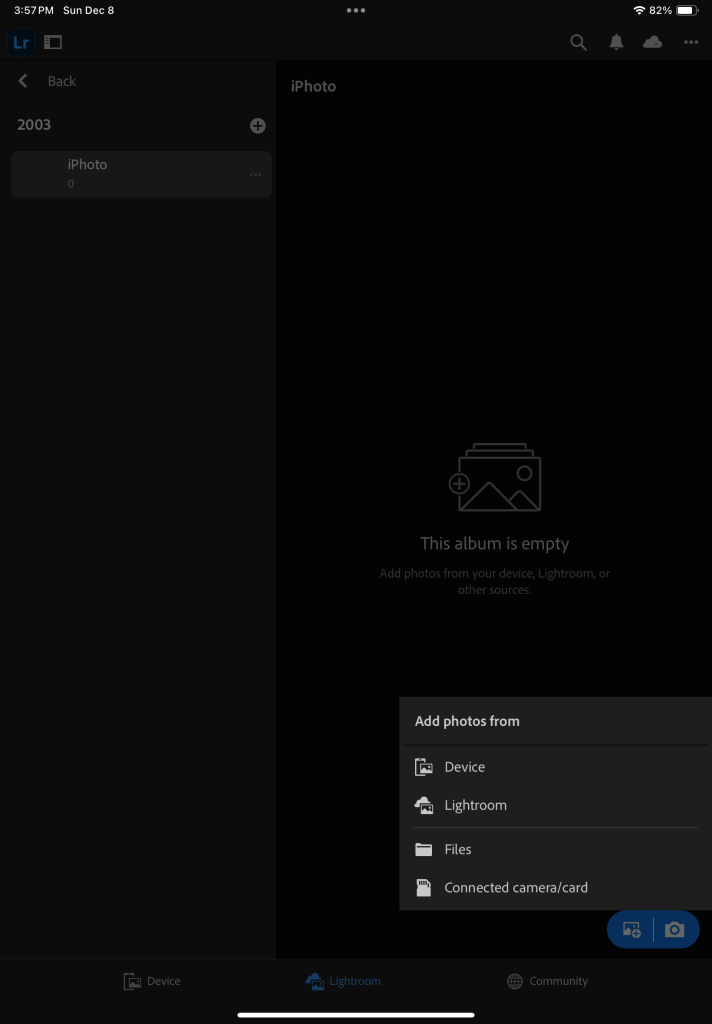

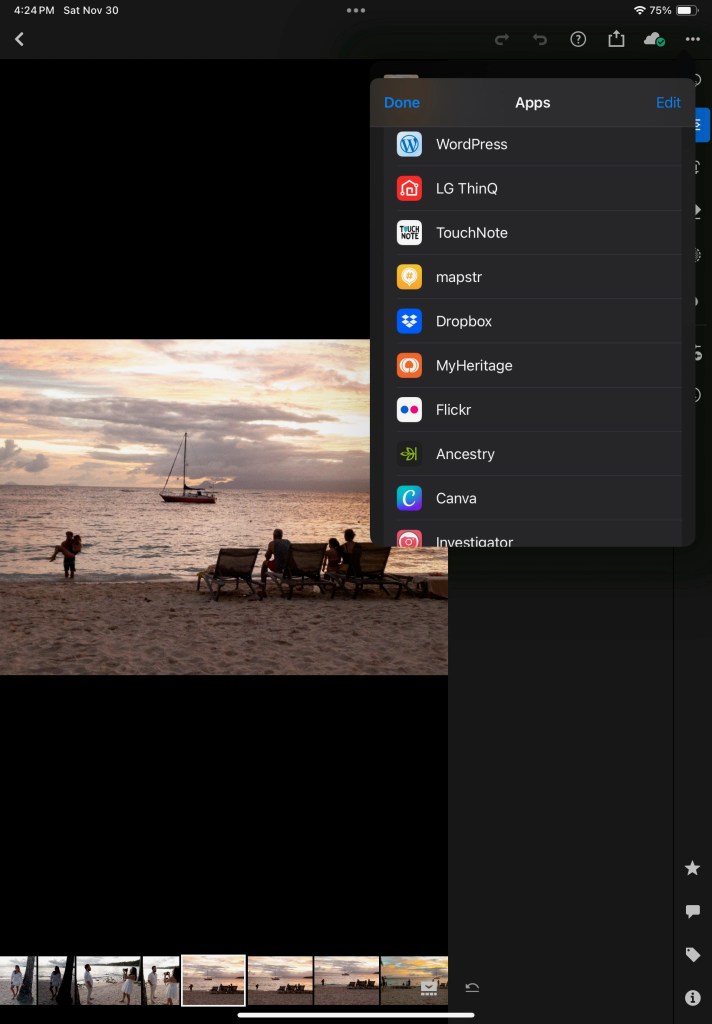

Importing the JPEGs to Lightroom Mobile (or Web) is a breeze – connect the media containing the files to the iPad or to a desktop/laptop (using the Web version on Lightroom in that case), create a folder and an album in Lightroom, and upload the pictures.

Experience has taught me that no technical solution is perfect, or eternal. I’ve seen Apple iPhoto and Aperture being abandoned, Lightroom migrating from a perpetual license to a subscription model, and multiple online image storing and sharing services fall into irrelevance or disappear.

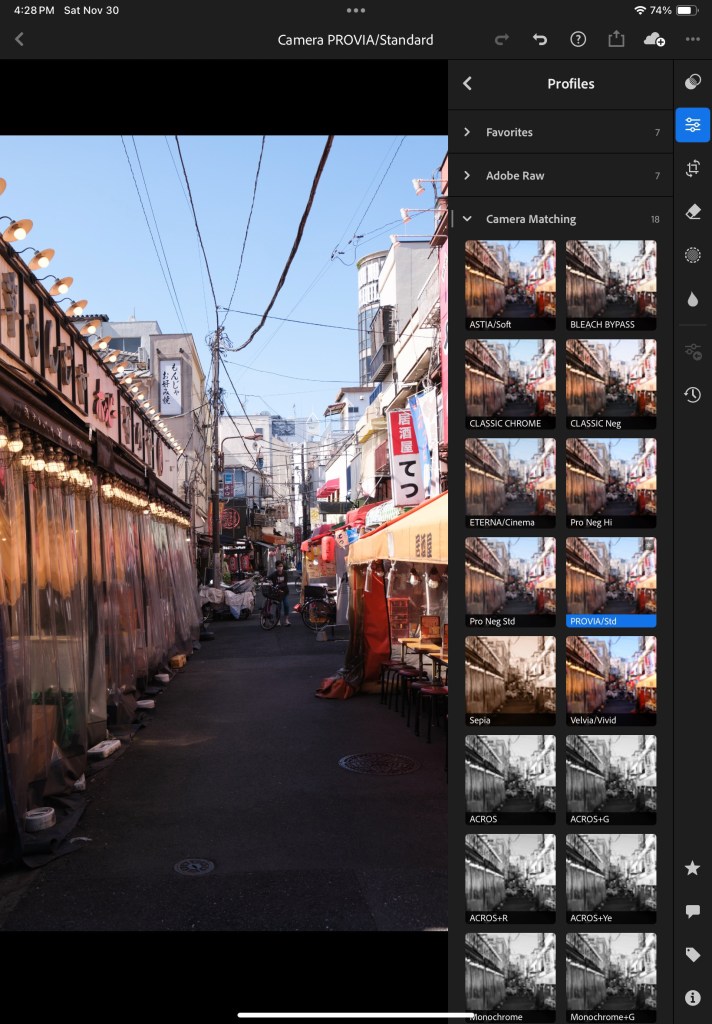

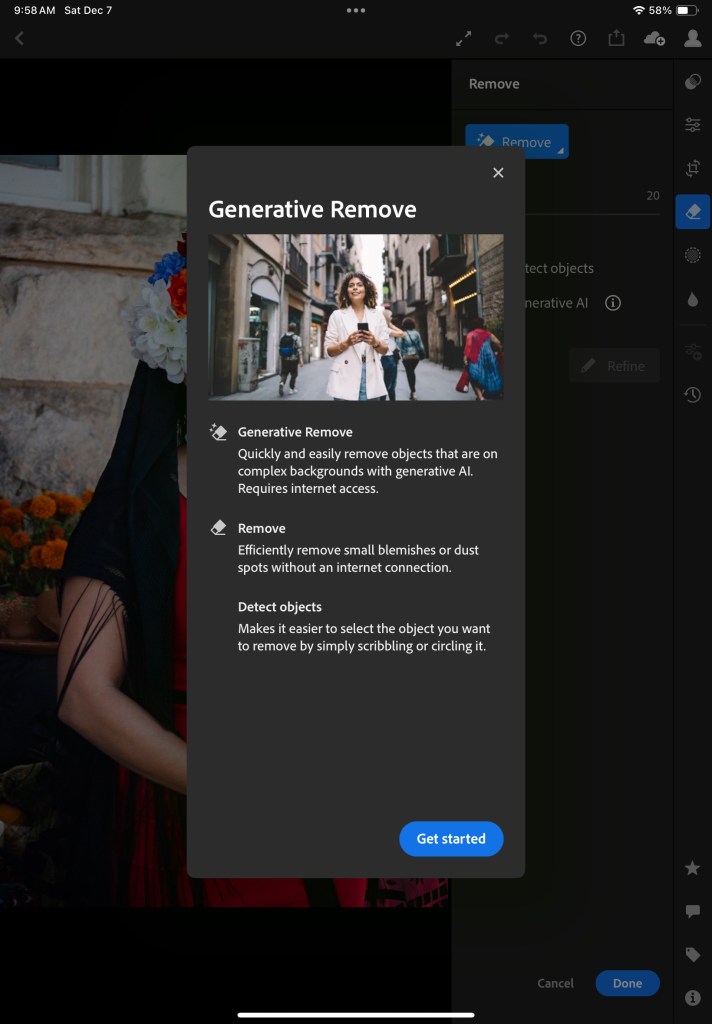

At this moment, Lightroom for Mobile with Premium features meets my needs, and I expect it will remain the case in the next few years. Eventually with an upgrade to 1TB of storage. The product is already mature, and it allows me to be laptop free – at least when it comes to photography. I expect Adobe to keep on working on their product. They’ve already started adding AI powered features to make photo editing or masking easier. I simply hope they will also find the time to address some of the little issues that irritate me.

More about the migration from Lightroom Classic (with local storage) to Lightroom (with cloud storage).

From the horse’s mouth: https://helpx.adobe.com/lightroom-cc/using/migrate-to-lightroom-cc.html