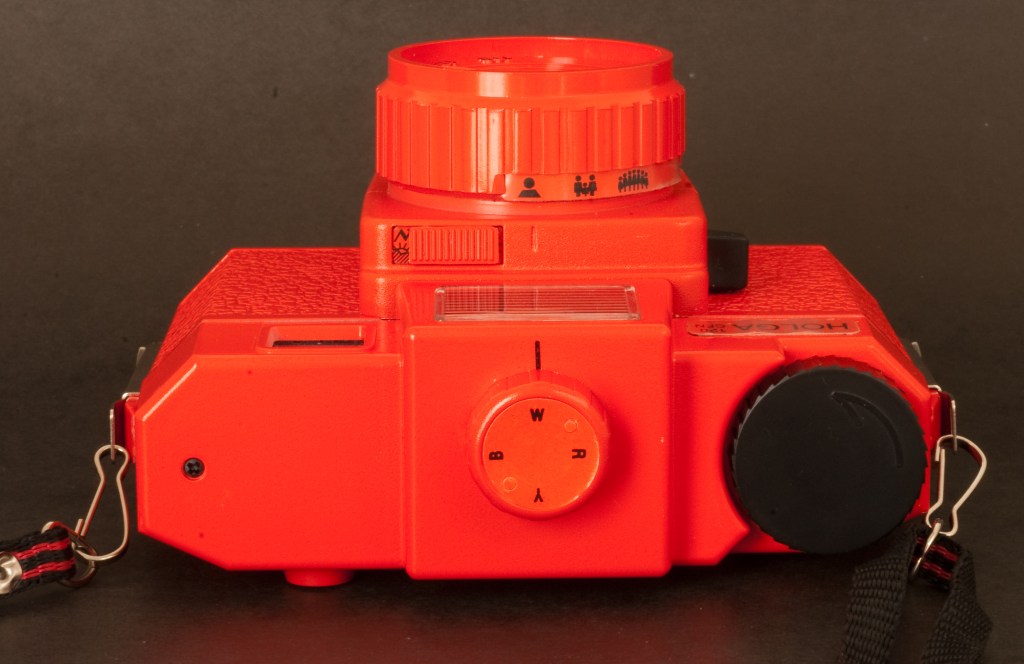

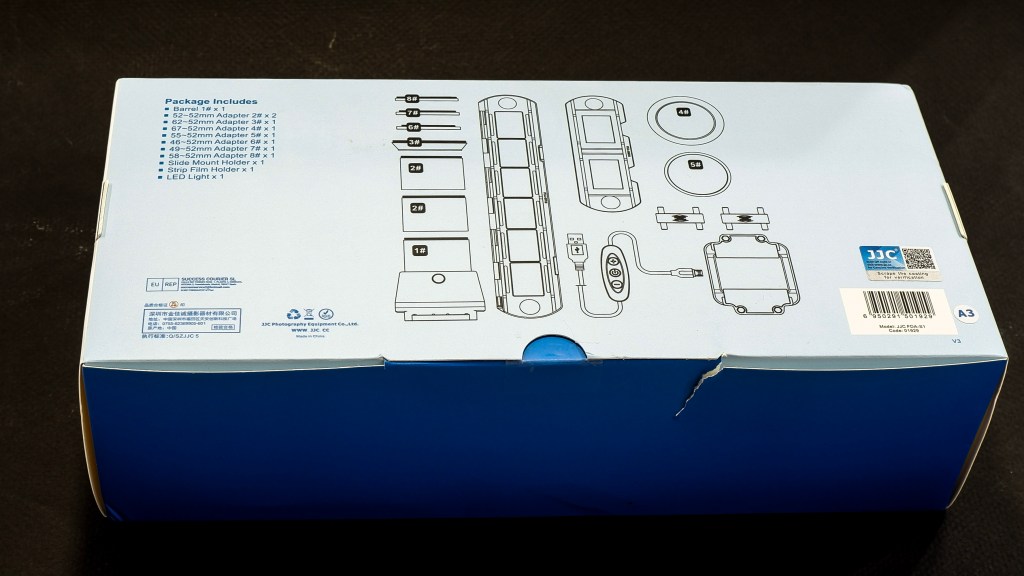

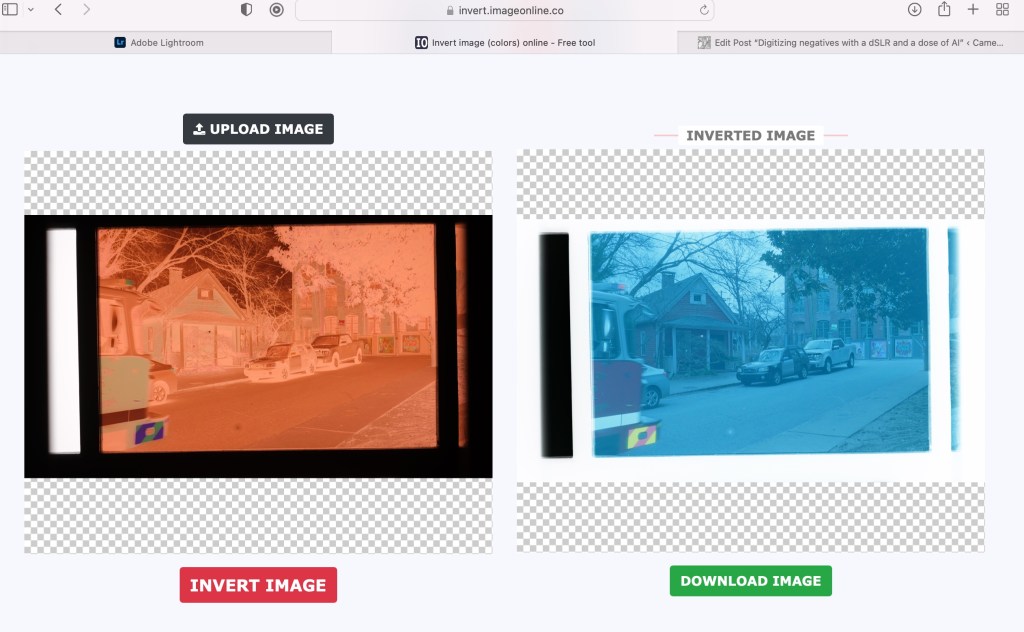

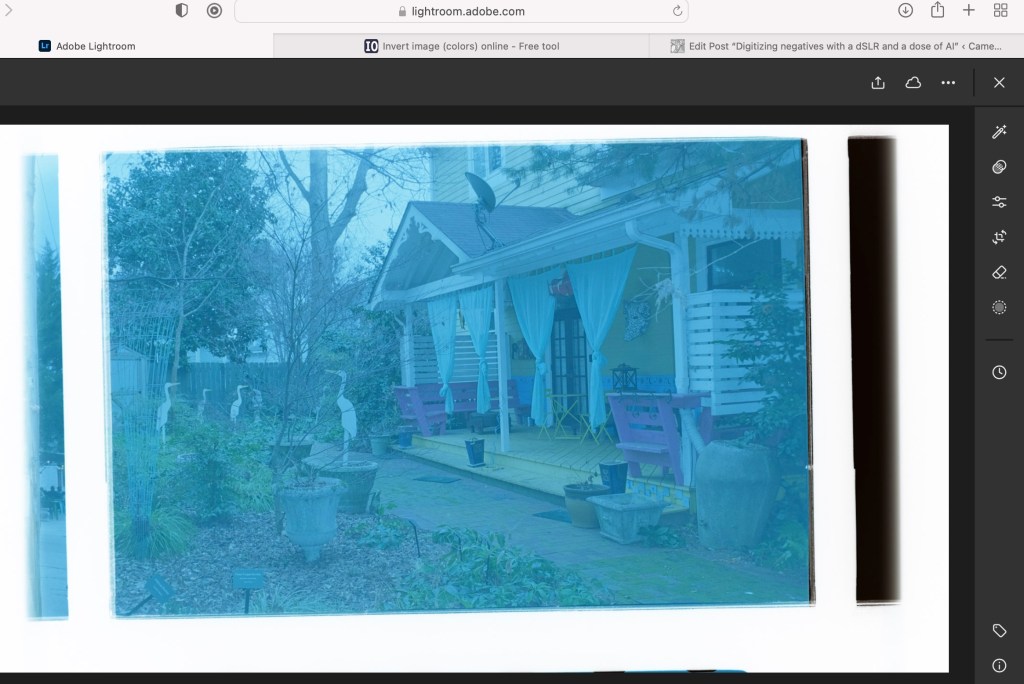

I had been tempted to start processing film again for a while, but I did not want to invest in dark room equipment or a dedicated film scanner. Two products launched recently, the Lomo Daylight Developing Tank and the JCC Film Digitizer, promise to make film processing at home easier than it has ever been, and made me take the plunge.

I ordered the “Lomo Daylight Developing Tank” a few weeks ago, and since I had just shot a few rolls of Ilford Black and White film, I put it to its paces.

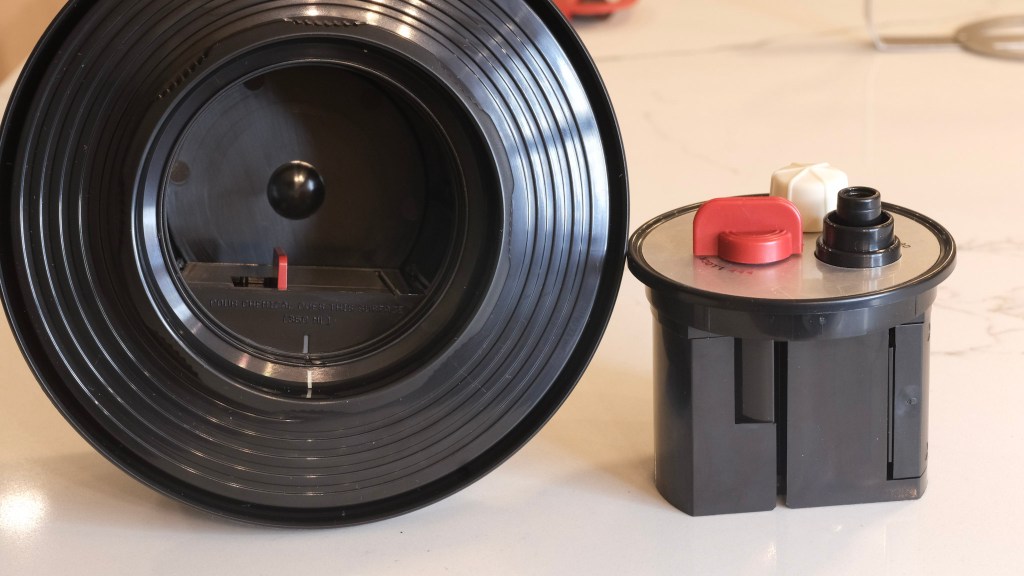

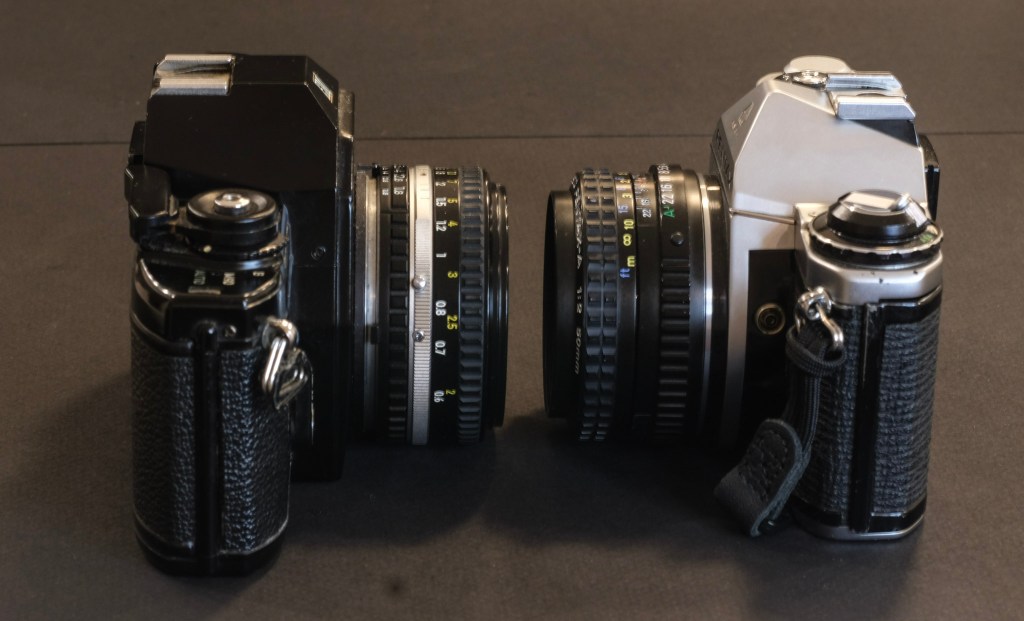

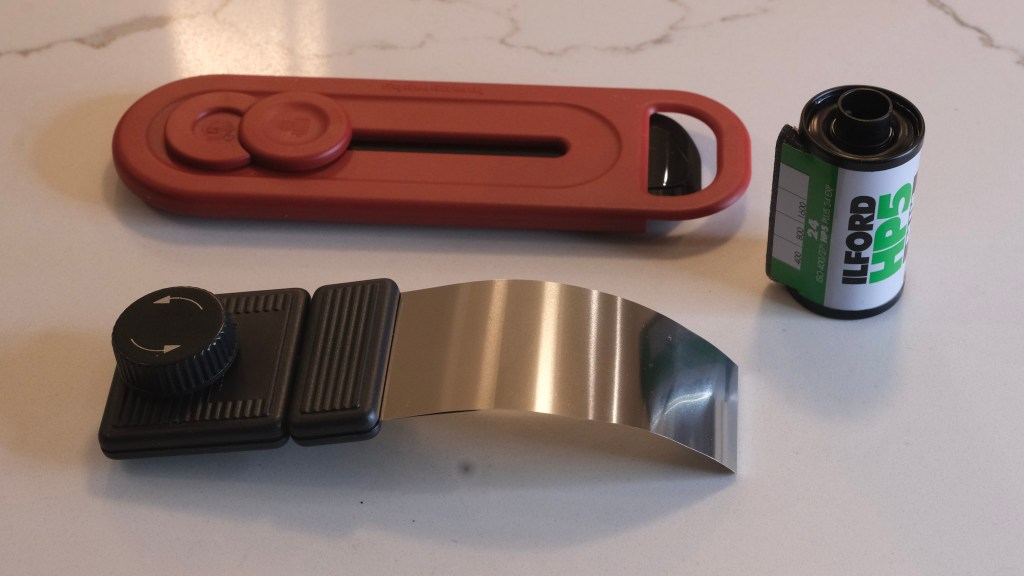

It’s probably best to watch the Youtube video posted by Lomo to see how it works. High level, the development tank contains a spiral reel (on the left in the picture below), and you will use the film loader (on the right) to move the film from the cassette to the spiral. In full daylight.

Let’s cut the chase: It works

The set (tank, spiral, loader, film extractor) is build of plastics of good quality and looks durable. It’s very cleverly designed, and it does the job:

- if you follow the instructions carefully (no user manual, watch the Youtube video at the bottom of this post), it works as promised, and in full daylight: cut the leader of the film, place the cassette in the loader, place the loader in the tank, turn the crank of the loader until all the film has been loaded on the spiral reel, turn a knob to activate a cutter that will separate the film from the cassette, remove the loader from the tank – and from then on, develop, agitate, stop, fix, agitate, rinse – as you would do with a conventional Paterson or Jobo tank.

- the film is not damaged in the process, and when you open the tank at the end of the development process, you see the film perfectly rolled on the spool.

- There is no light leaks, and no stain on the developed negatives – the system obviously respects your film.

- It seems to be fool proof – while I was struggling with a piece of debris (user error, more about this below), I may have lost a few frames, but the rest of the film was never at risk and gave me negatives I can be proud of.

So, is it the greatest invention since sliced bread, or a solution in search of a problem?

Well, somewhere in between – it’s a clever system, but there are couple of drawbacks.

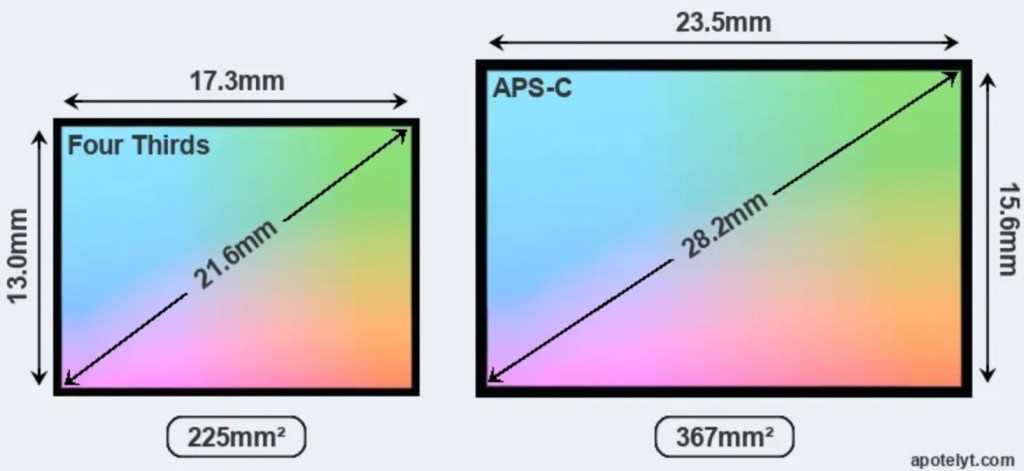

First, you can only develop one roll of 135 film at a time, when the “market standard”, the Paterson Universal System 4 Development tank, has room for two rolls of 135 film. And because the capacity of a Paterson tank is 600ml, most single use processing kits are designed to be diluted to produce a 600ml solution.

Unfortunately, the capacity of the cuve of the Lomo is 350ml – so you need to dilute a bit more if you want to process two rolls of film with one dose from a standard processing kit.

Secondly, the film should not be fully rewound, and the film leader should be accessible. If you use a darkroom bag and load your conventional Paterson cuve in the bag, it does not matter that the film leader is still accessible or fully rewound in the film cassette, since you’re going to use a cassette opener to access the film. It’s different with the Lomo.

The Lomo Developing Tank’s loading mechanism only works if the film leader is accessible – if the film has been fully rewound in the cassette, the photographer will have to use a film extractor to pull the leader from the cassette. There is one included in the kit, and it works reasonably well for a film extractor, but it’s an extra step that the user of a darkroom bag would not have to perform.

Thirdly, when the loader is finished loading the film on the spool, the operator has to turn the red knob to the left to cut the last section of film and separate it from the cassette – so that the loader (and the now empty cassette) can be removed from the cuve. You have to fully, and decisively, turn that knob to the left.

Because it could happen (it happened to me) that if the cut is not perfect, a little tiny bit of film is kept prisoner in the cutting mechanism and obstructs the very narrow slot where the next (undeveloped) roll of film is supposed to pass to reach the spiral reel. It makes loading the film impossible, until you have found that tiny piece of film and removed it. Lessons learned, the hard way.

Lastly, when you cut the film to separate the section which is reeled on the spiral from the cassette which still sits in the loader, a short length of film remains attached to the cassette (11 perforations, approximately two inches or 5cm), which (depending on the camera and how you loaded the film) may (or may not) mean that the very last frame of each roll of film will not be processed, and will be lost forever.

As a conclusion

The main benefit of the Lomo Daylight Developing Tank is that it makes film development at home less intimidating for the beginners.

They won’t have to use a darkroom bag, and won’t need to learn how to operate a cassette opener and load the film on a spiral reel just by touch, without seeing what they’re doing.

With the Lomo Daylight Developing system, everything takes place in full daylight, and does not require any particular skill, experience or muscle memory. If the equipment is clear of any film debris and you follow the instructions, it simply works.

The system is intelligently designed, seems carefully built using components of quality, and should withstand the test of time.

At $89.00, it’s probably a bit more expensive than a good quality set composed of a universal tank, a darkroom bag and a cassette opener, but not by much. And as an easy introduction to film processing, it’s worth it.

But…

Does it save time? I doubt it.

First, unless your camera can be set not to fully rewind the film and leave the leader outside of the cassette (or you remember not to fully rewind it if you use a non motorized camera), you will have to extract the leader with a specialized tool before you can place the film cassette in the loader of the Lomo system.

Which is a step you don’t need to go through if you use a darkroom bag and a cassette opener.

Secondly, after you’ve developed your first roll of film of the day, you will have to carefully disassemble, rinse, dry and patiently reassemble the whole system, which takes definitely more time than simply rinsing the components of a Paterson tank.

And if you want to avoid the trouble I experienced with the second roll of film I processed, you will thoroughly check that there is no tiny piece of film obstructing the film insertion slot inside the cuve.

If you are already equipped with a darkroom bag, a cassette opener and a conventional development tank , and know how to use them, I honestly don’t see any benefit in switching to the Lomo Daylight Developing Kit.

And I would not consider developing color film (whose chemistry is much more temperature sensitive) in a Lomo Daylight as well.

As for me? It’s been ages since I used a conventional development tank and a darkroom bag for the last time. I’m pretty sure I would still be able to use it, but I was not be able to locate my old kit – probably lost when moving from one place to another. I had to start afresh. So why not try something different?

The Lomo Daylight Developing Tank is not perfect. It will not be as efficient at processing large quantities of film as a conventional Paterson or Jobo development tank, but I’m not planning on processing a large volume of film (one or two rolls of black and white film per month at the most).

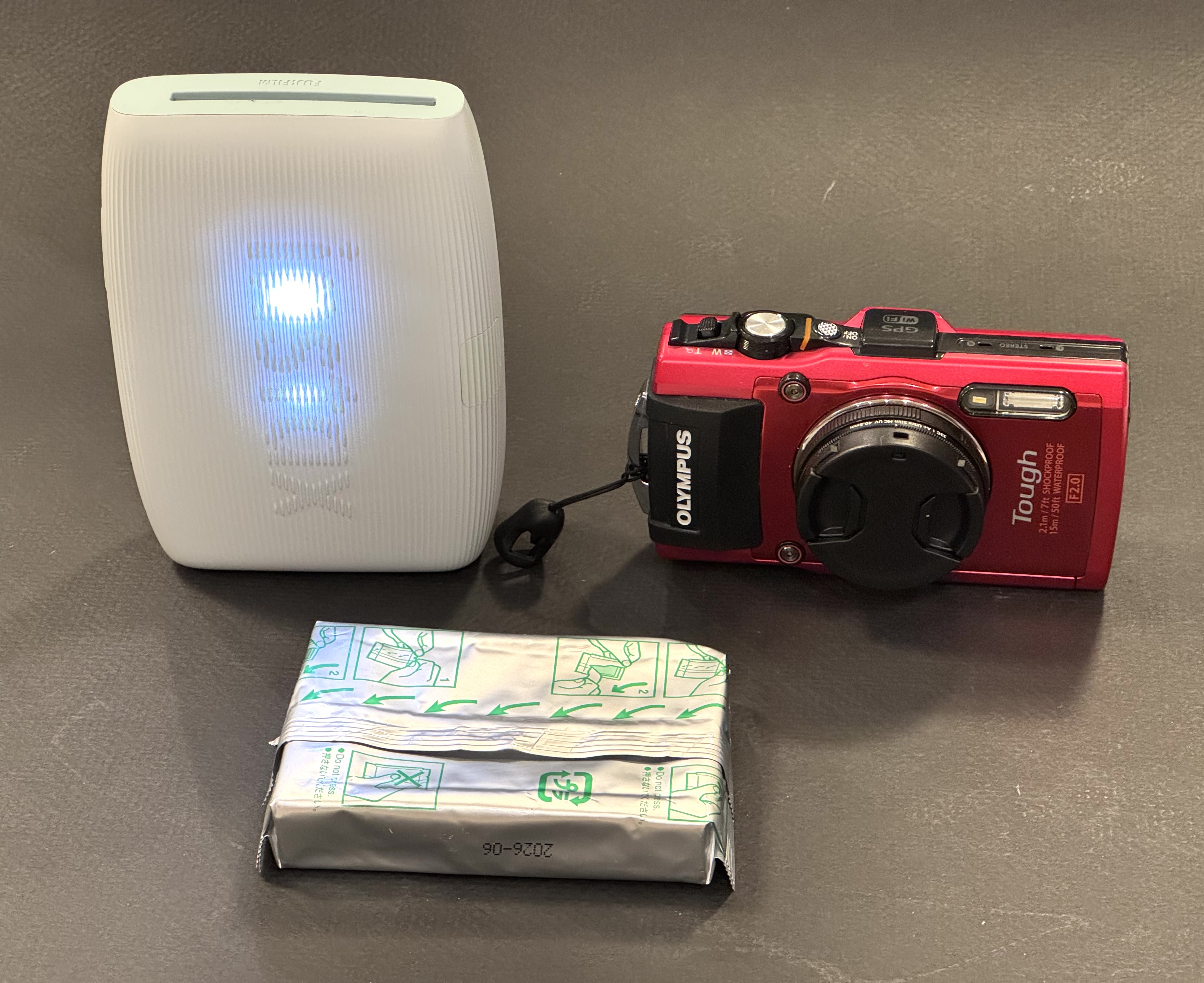

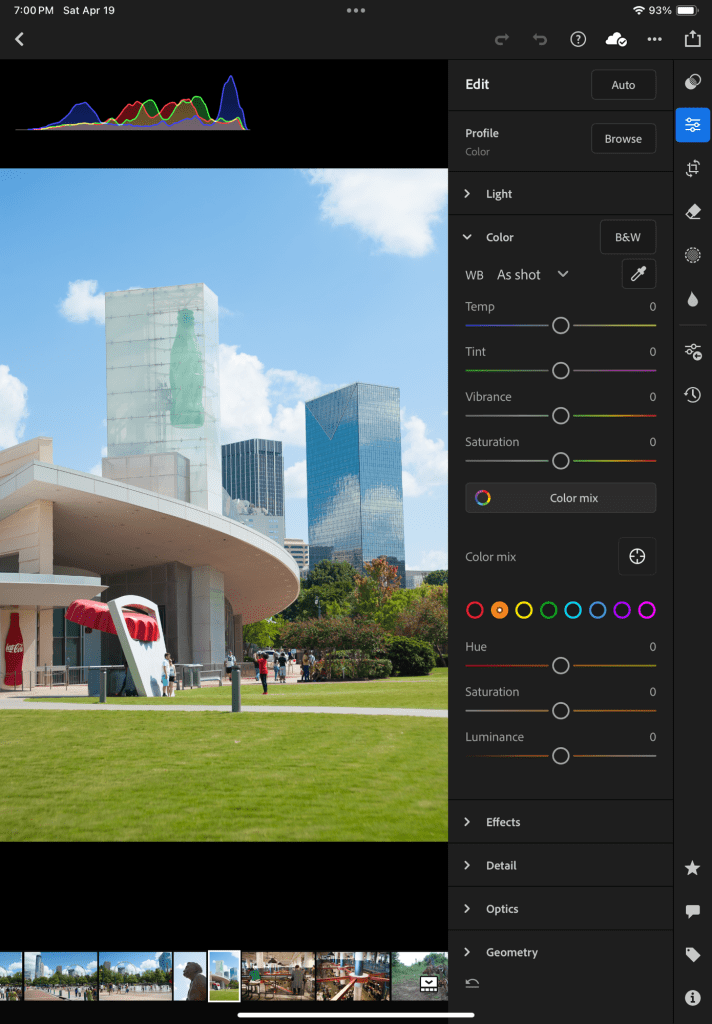

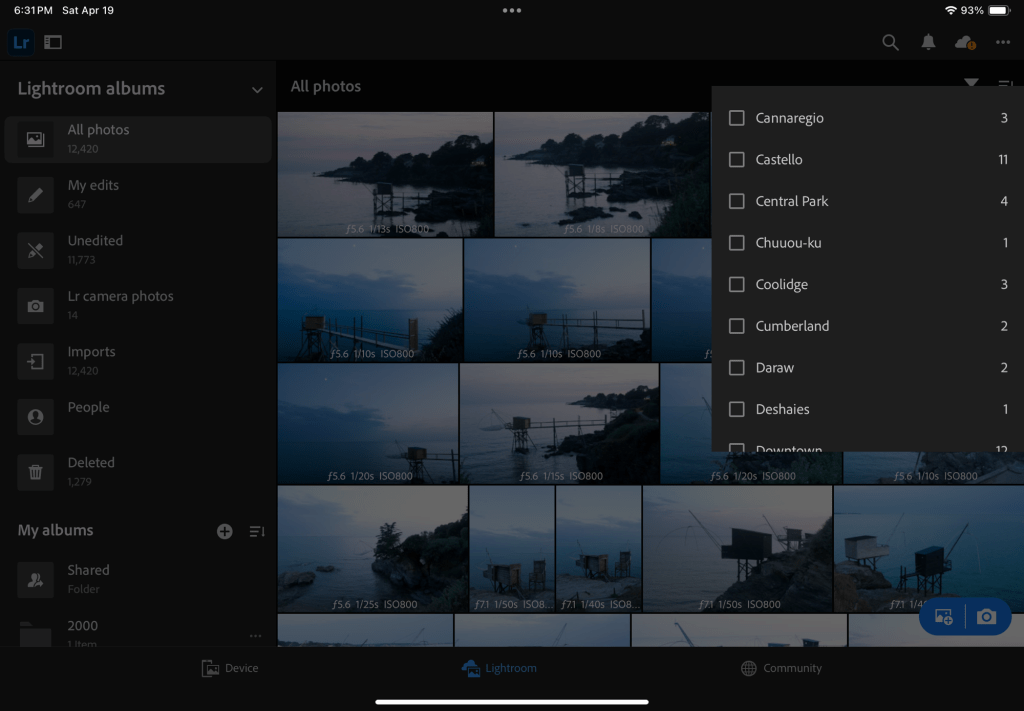

For my use case, the Lomo Daylight makes sense. And used in conjunction with the JJC Digitizing kit, it will give me access to my images a few hours after they have been shot, with a minimal hassle, and no darkroom.

More about the film processing at home in CamerAgX

More reviews

Another test of the Lomo Daylight Developing Tank on 35mmc.com: https://www.35mmc.com/21/04/2025/lomo-daylight-developing-tank-a-review/

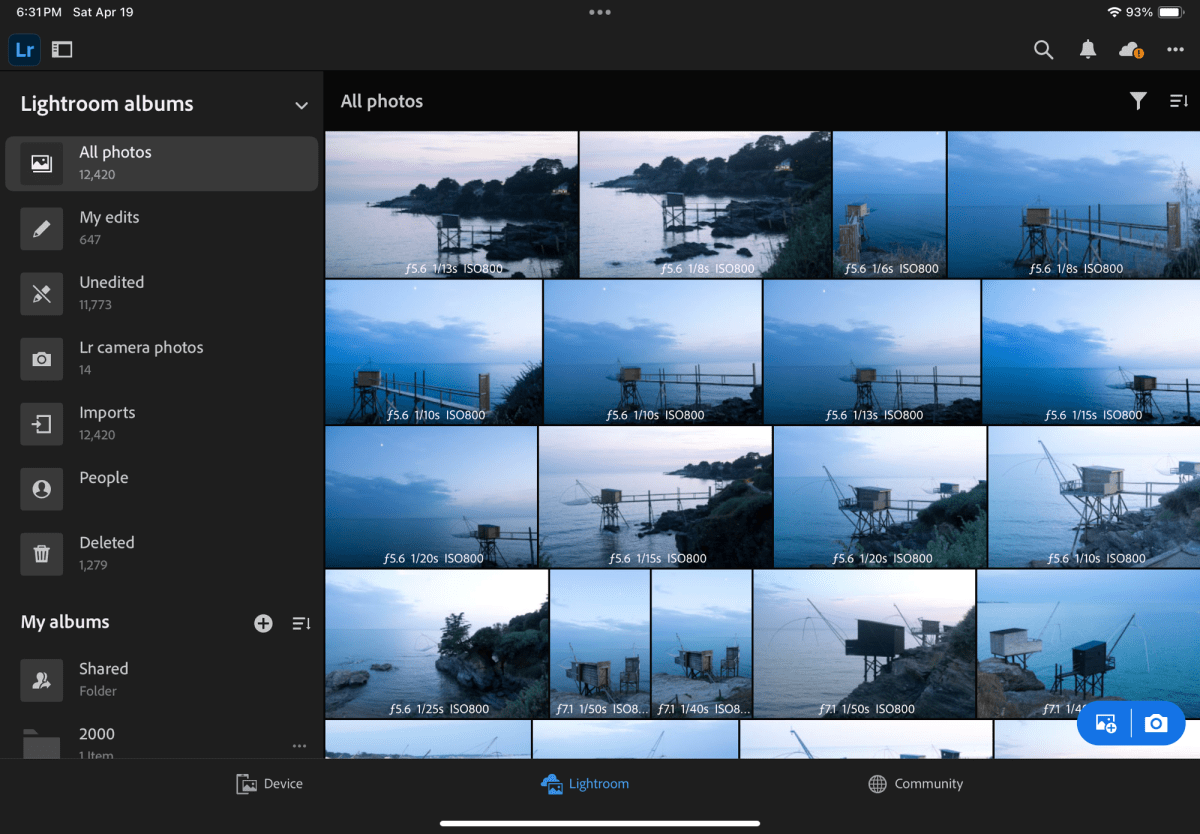

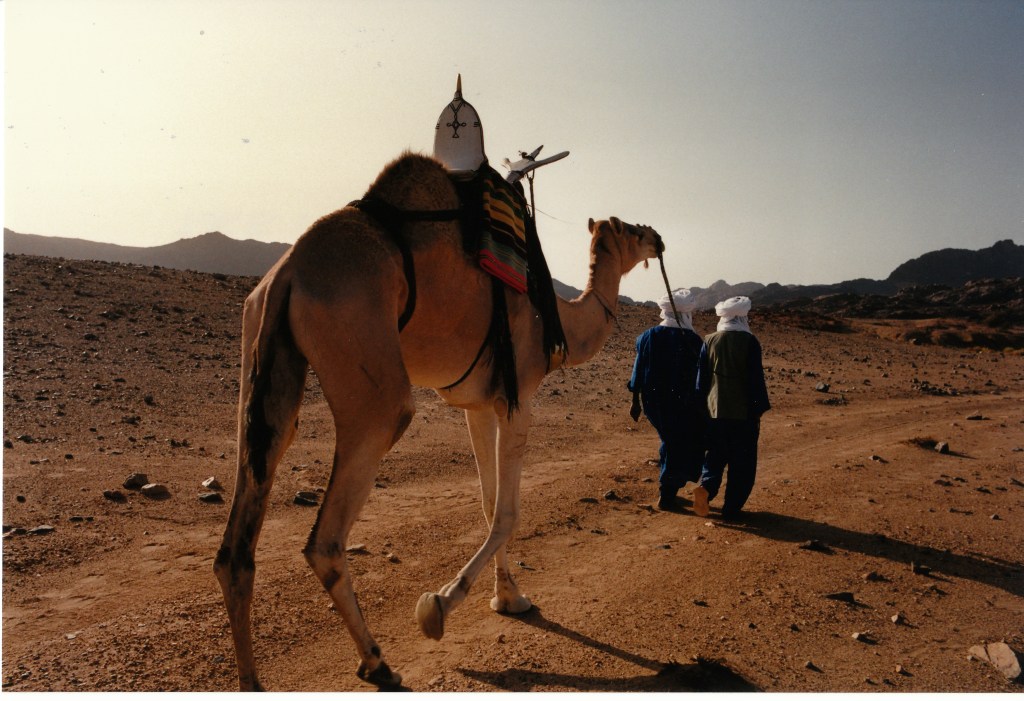

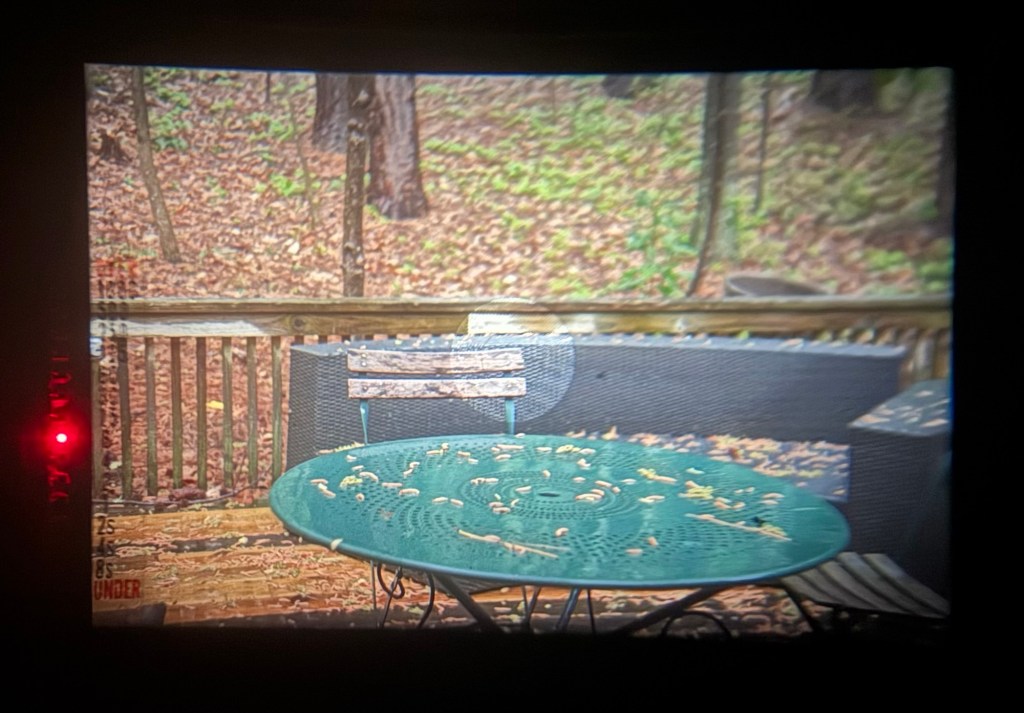

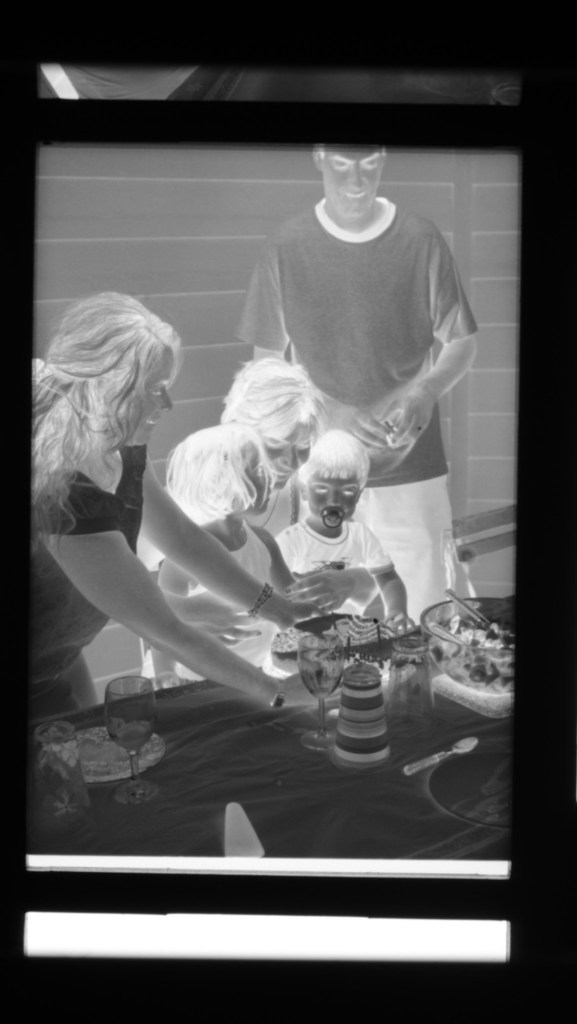

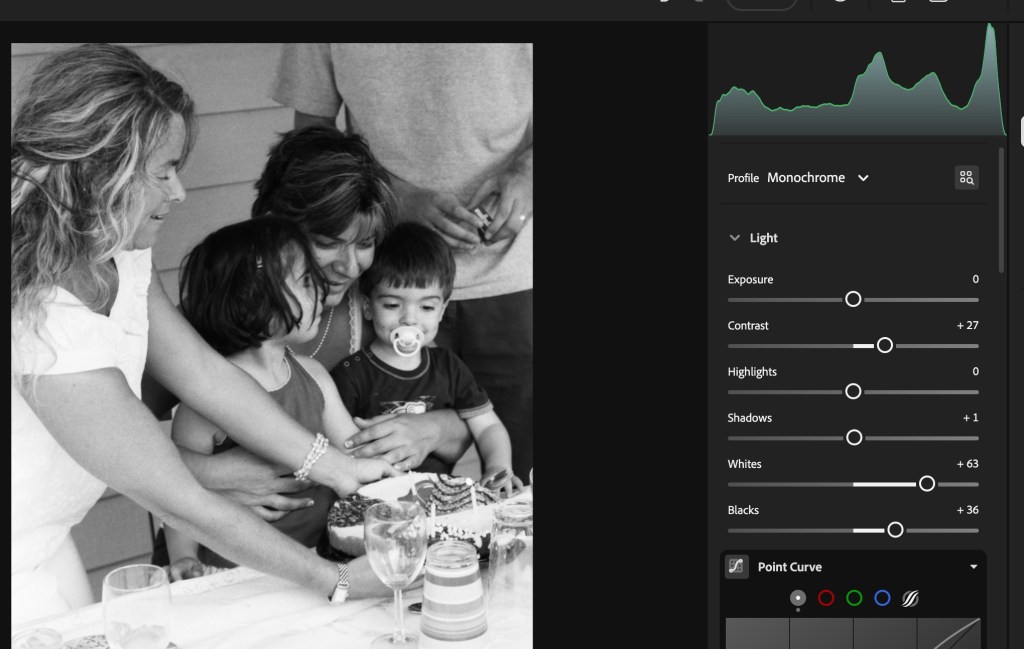

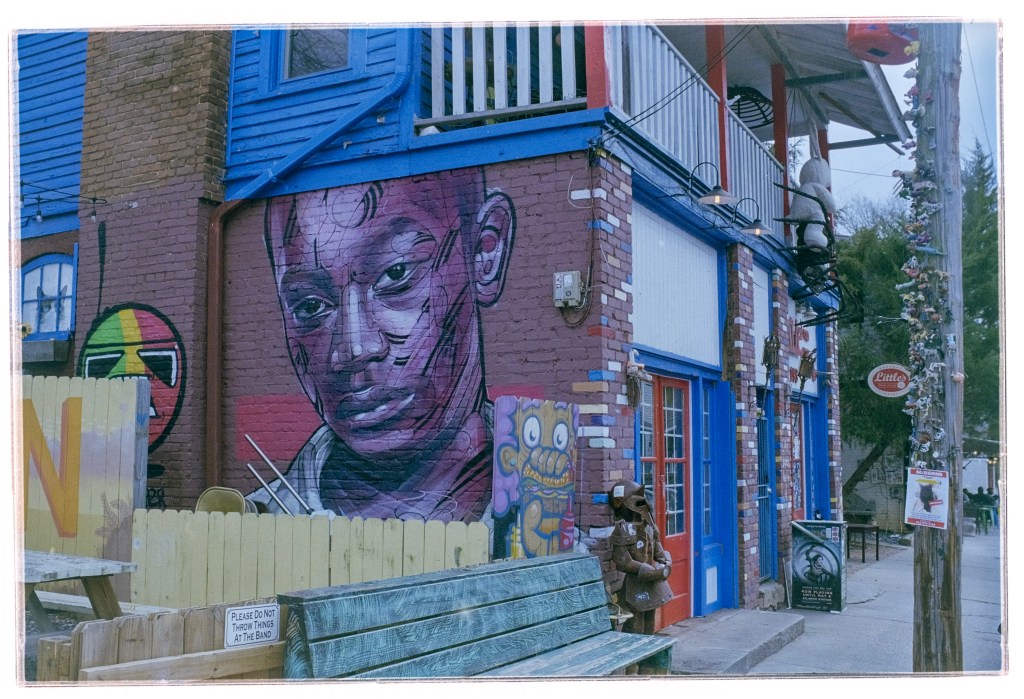

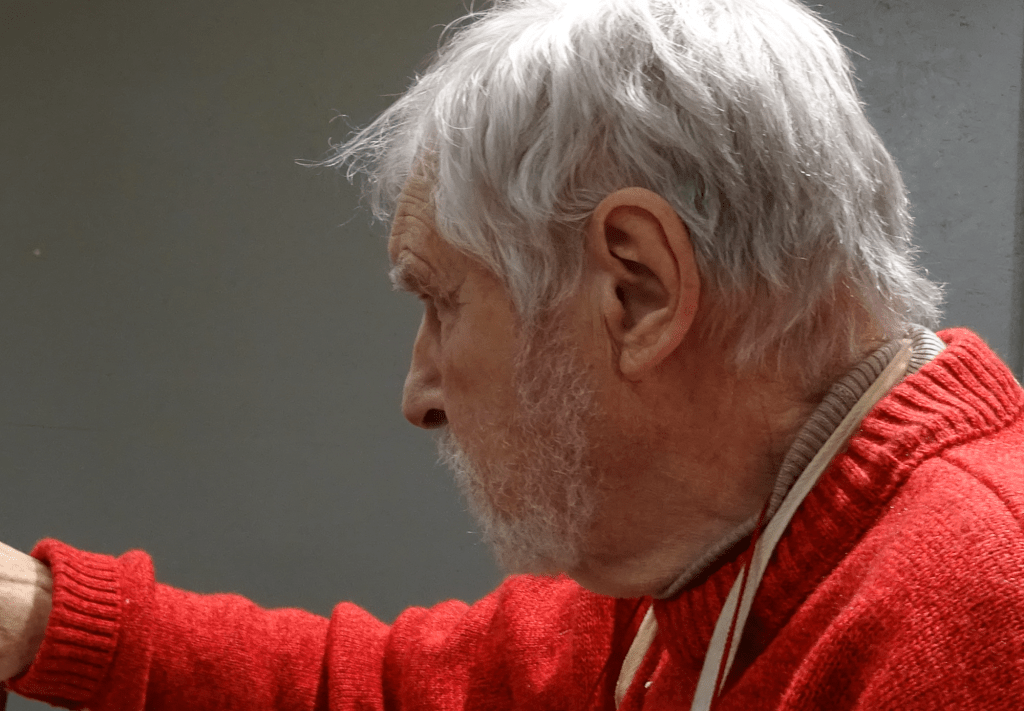

The reward

The first roll (HP5 Plus) was not a complete success – my bad – I did not configure the timer correctly, but I’m pleased with the second roll (Ilford FP4 Plus)