What camera to pick when you’re new to film photography and want to shoot with something a bit better than a point and shoot camera? The question is still bugging would-be film photographers in 2025. In the late nineteen seventies, Japanese camera manufacturers were trying to attract new categories of users to their single lens reflex systems, and started launching small, light and cute SLRs, easier to use and less intimidating than the big, heavy, complex and expensive best sellers of the time.

In order to make those cameras easy to use, they embraced the KISS principle (keep it simple, stupid) and deprived those entry level cameras from features and controls that seasoned photographers were taking for granted – they only operated in automatic mode, and generally did not even have a shutter speed dial.

Pentax opened the way with the ME in 1976, followed (in no specific order) by Olympus (with the OM-10), Canon (with the AV-1), Fujica with the AX-1, and least but not least, Nikon. Until that point, Nikon had always tried to convey the image of a manufacturer of high quality products, sold at a premium over the models of its competitors. The Nikon EM from 1979 was a big shift – the privilege of shooting with a Nikon SLR was being made available in a simple camera, at a price point in line with the competition.

Almost 50 years later, cameras like the Nikon EM or the Pentax ME are among the cheapest SLRs manufactured by a first tier brand. Good copies typically sell between $50 and $100, when cameras generally recommended for beginners, like the Pentax K1000 or the Canon AE-1, can command prices above $100, and really nice cameras of the same vintage like the Nikon FE2 routinely reach prices in excess of $300.

The Nikon EM

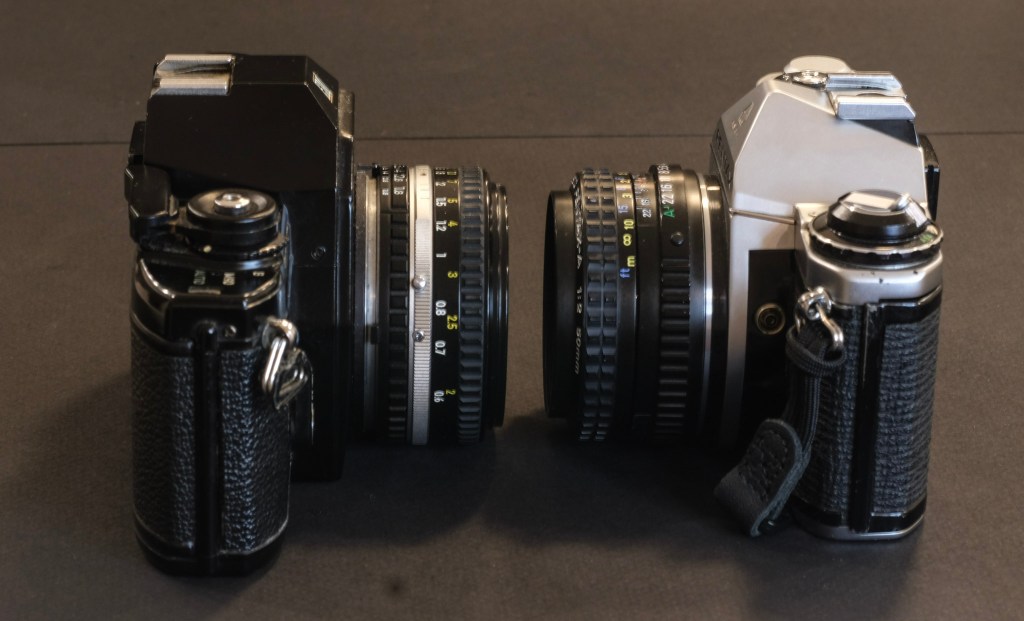

Like the Pentax ME, the EM is an ultra-compact camera, operating only in aperture priority mode, and deprived from a shutter speed dial and from a depth of field preview lever. Besides the logo on the front of the prism and the bayonet mount, the biggest difference betwen the two is that the shutter speed selected automatically by the camera is indicated by a needle moving on a scale at the left of the viewfinder on the EM, while the ME relies on red LEDs.

Following the example of Pentax with their M series lenses, Nikon developed a line of more compact and lighter lenses for this model (the E series lenses). The 50mm is almost a pancake lens – with an excellent image quality in spite of its really small size (the E series 35mm f/2.5 is also one of my favorites).

Pentax had launched the ME Super and the Super-Program for the photographers who expected more controls on a SLR. Similarly Nikon derived the FG from the EM, with a shutter speed dial and a program auto exposure mode.

The lineage of the ME stopped with the Super-Program and Program-A , the EM’s with the FG20.

Comparing the EM with the ME

The ME and the EM have 4 things going for them today:

- they’re incredibly small, in particular with an “almost” pancake lens like the Nikon Series E 50mm or the Pentax M 28mm lens.

- they’re nicely finished, – the EM was only available with a black finish, and although the external shell is made of polycarbonate, it still looks cool today, while the ME – still built entirely in metal, has a few clever details (such as the film advance indicator) and a nice detailing.

- Almost any lens made by Nikon or Pentax between (roughly) 1975 and the first years of this century can be mounted, including autofocus lenses.

Above all, they’re simple – you set the aperture, place the subject in the frame, adjust the focus, and shoot. Even simplified, they’re still real cameras – with a good viewfinder with precise focusing aids, a direct control of the aperture and an indirect control of the shutter speed.

They have a few things going against them as well:

Because they’re somehow over simplified, they are more difficult to bring to do exactly what you want than a semi-auto camera or a camera with multi-mode automatism. An experienced photographer will be able to work around it, but beginners will be limited in their progression:

- the control of shutter speed is indirect only (you have to adjust the aperture so that the automatism reacts by adjusting the shutter speed – there is no shutter speed dial and therefore no semi auto mode).

- there is no exposure memorization either, only primitive exposure compensation systems. The exposure compensation for backlit subjects is either too simple (-2 EV at the push of a button is the only option on the EM) or too complex for beginners (expo compensation dial on the film sensitivity dial for the ME).

- there are some irritating quirks – the EM beeps all the time (every time it believes the exposure is going to be under 1/30sec or reach 1/1000 sec). On the ME (and all the ME derivatives up to the Super Program), the control knob around the shutter release button is difficult to use unless you have the fingers of a garden fairy.

The real issue with those two cameras is that in the same price range you can buy the follow up models (Nikon FG, Pentax Program-A and Super Program) that keep most of the good points (small size, beautiful finish, choice of lenses) but are even simpler to use (there is a program mode) and simpler to over-ride (there is also a semi-auto mode).

In summary

The EM does not cut it for me. It may be marginally more capable than the Pentax ME (the exposure compensation button is convenient), but the beeps are too irritating. On the FG there is a switch to silence the beeper, but not on the EM. The EM and the FG also seem more fragile than their bigger brothers in the Nikon range. The real problem with the EM (and the FG to a lesser extent) is that they were stepping stones in a range of cameras which included real gems. In the Nikon line-up of the late seventies/early eighties, the FM and the FE offer more flexibility, and a more robust built. Admittedly these two are a tad more expensive and a bit heavier than the EM, but not much larger and nicer to use. As for the FM2 and the FE2, they’re in another league altogether.

On the other hand, the Pentax ME and its descendants were not a low cost point of entry in the Pentax family, they were all that Pentax had to propose if you wanted to use Pentax SMC lenses. I like the Pentax ME – it’s nicely built and refreshingly simple – I even prefer it to the Super-Program, which is more capable but also more complicated to use, and requires even smaller fingers to change the settings. In the Pentax family, I still have to put my hands on the Program-A – it’s a slightly decontented Super-Program (no shutter speed priority mode) and it may be marginally simpler and easier to operate than its “Super” brother.

As a conclusion – which one is the best for a beginner?

For a beginner, what makes the difference between two cameras should be the availability of good lenses, and any Nikon and Pentax SLR of that vintage will accept an extremely broad selection of very good prime and zoom lenses, manual focus as well as autofocus.

As cute, easy to use and cheap as they are, the EM and the ME will not be as flexible as a Nikon FG or a Super Program, and the cost difference between those cameras and a Nikon FE amounts to the cost a few lattes at Starbucks.

If you choose Camp Nikon, my recommendation will be to brew your coffee at home for a few days and use the cash you save for the FE. And if you still want your coffee at the drive-thru window, buy a FG rather than an EM. It will let you grow higher as a photographer than the EM.

For Pentaxists, it’s not as clear cut. There is no visible difference in build quality between a ME and a Super Program, and some features present in a Nikon FE and important for an enthusiast photographer (exposure memorization) are still absent from the Super Program. Simply avoid the models with a bad reliability record (ME Super?) and only buy cameras thoroughly tested by their seller.

As a final note, if you’re looking for the absolute bargain in the Nikon world, I suggest you also look at successor of the FG, the Nikon N2000 (F301 in the rest of the world). It’s the twin brother of the better known autofocus N2020 (aka F501), but without the autofocus mechanism, and with a ground glass designed for manual focus operations. With the N2020, it shares the motorized film advance, the semi-auto, program and aperture priority modes, an AE lock button and a great viewfinder. It’s a bit larger than cameras like the EM or the ME (and not as cute for sure), but it runs on AAA batteries that you can find anywhere, and it’s so cheap….one of my preferred $20.00 cameras.

More about cameras I recommend for beginners to film in CamerAgX:

In addition to some of the cameras mentioned above, there are a two other cameras I would recommend for beginners, and if you need more information, the full list of cameras reviewed in this blog since the beginning.

In the meantime….

I’ve not had time to finish (and process) the rolls of films I loaded in the ME and the EM. So far, I tend to prefer the ME, because it does not beep like crazy, and also probably because it’s in a better shape than the EM, which is a bit scruffy. I find the LEDs indicating the shutter speed in the viewfinder of the ME easier to read than the needle of the EM, whose movements tend to be erratic – but again it may be a reflection of the better state of conservation of the ME.

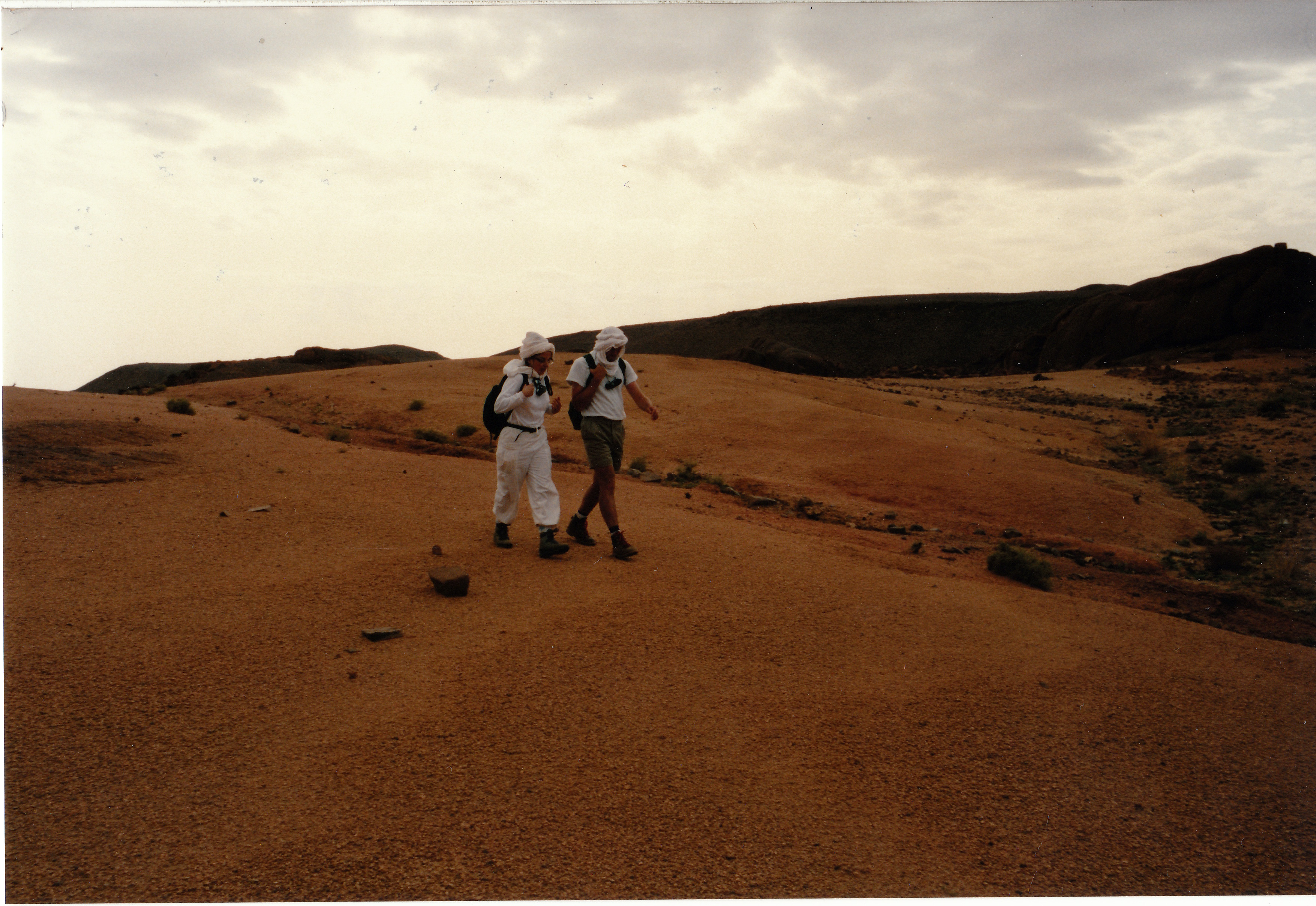

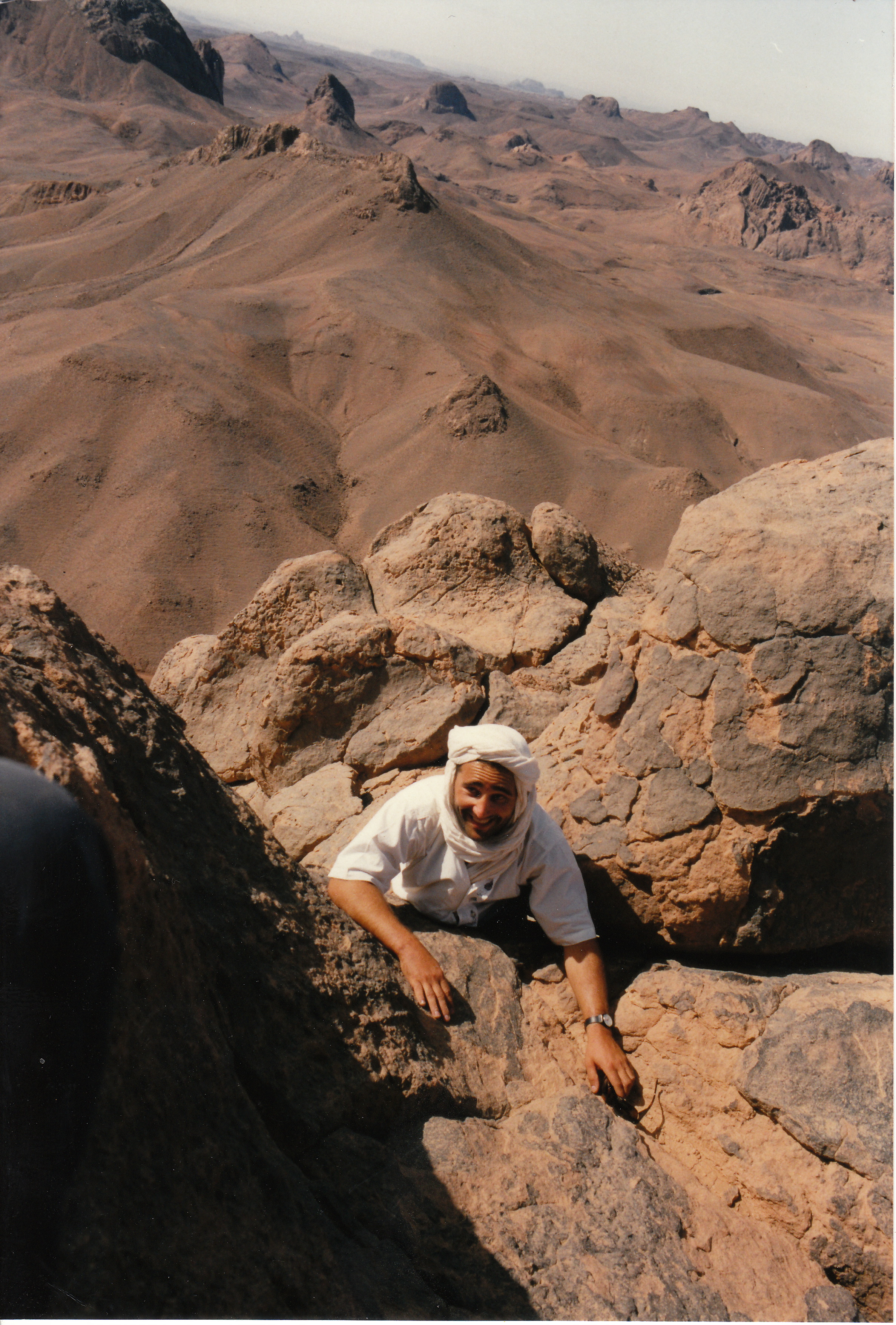

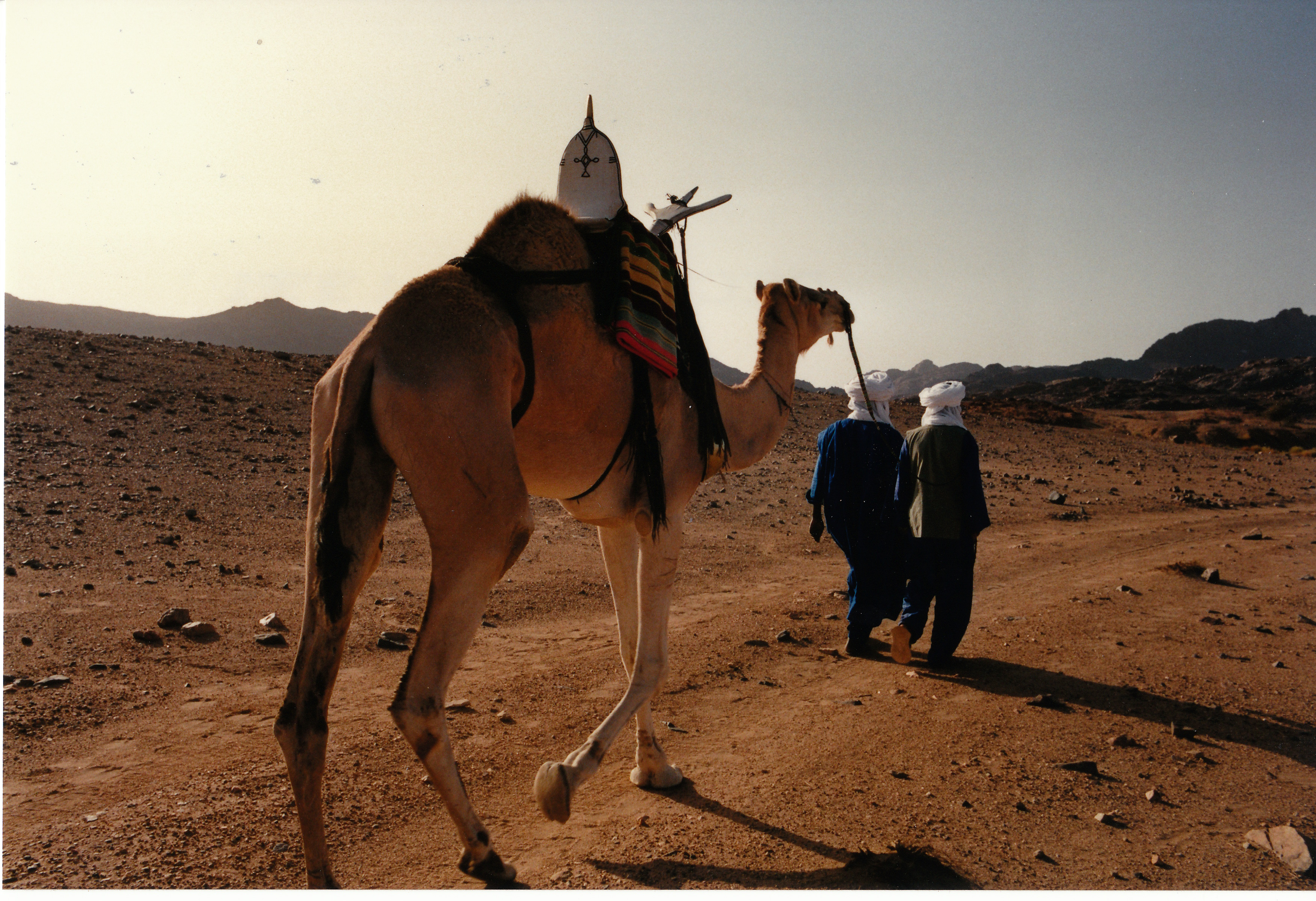

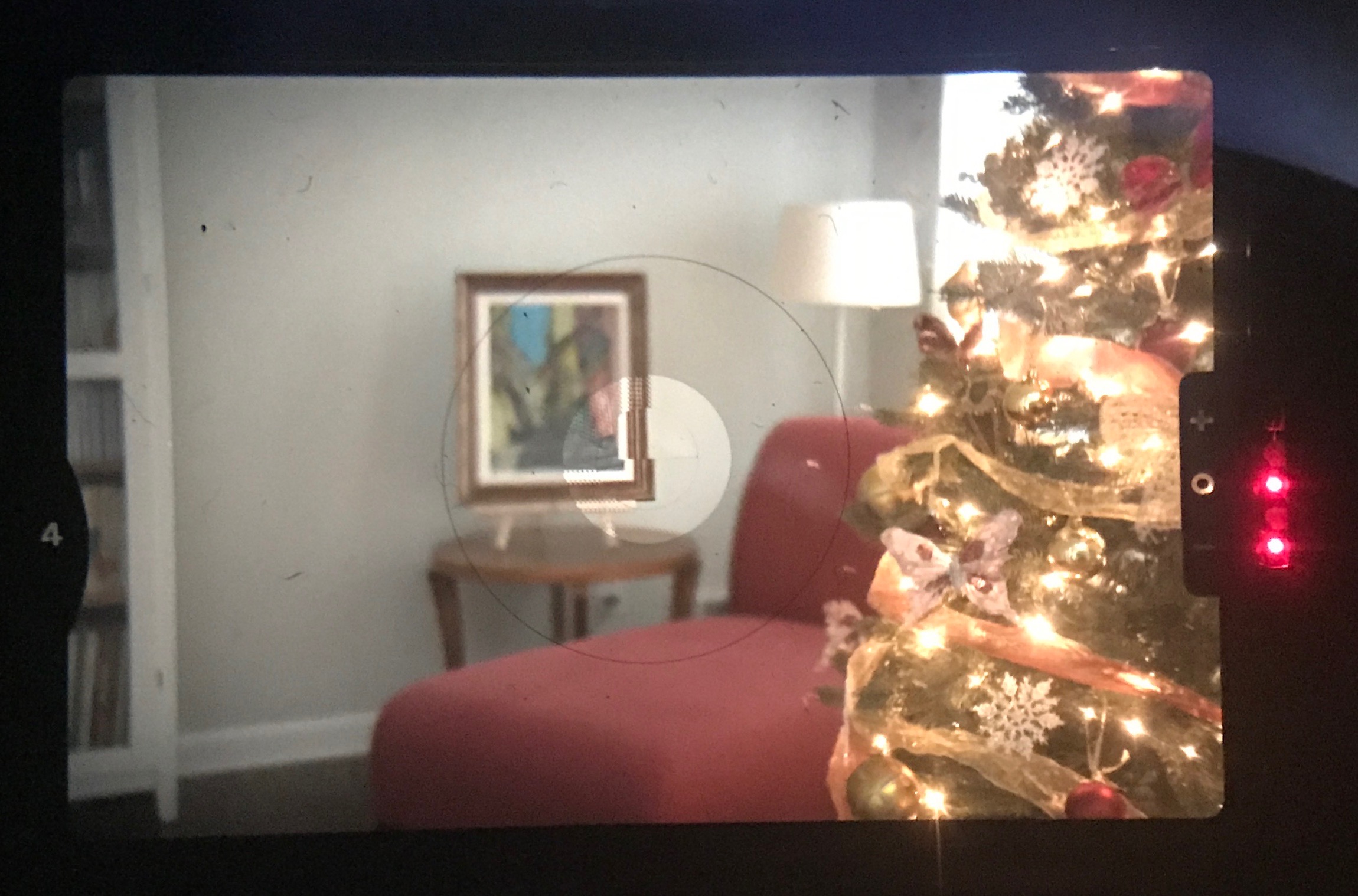

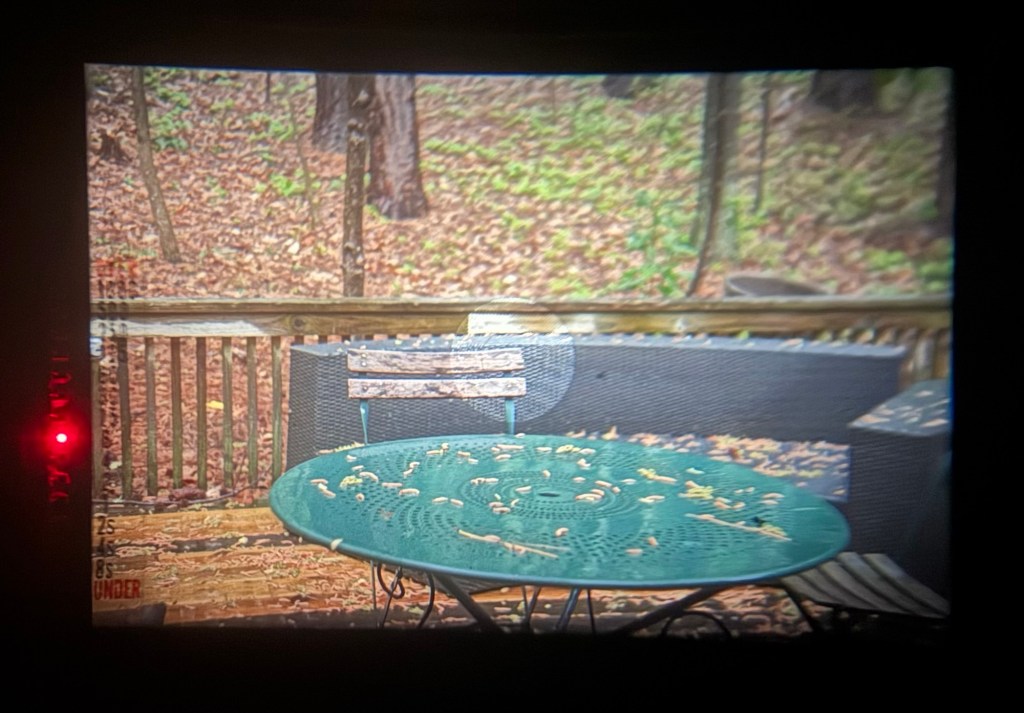

Two pictures shot with cameras of the same family – the Super Program and the FG.