Originally published in September 2009.

I don’t have this camera anymore. I’m afraid it ended its life in the trash can – not economically repairable – a few years ago. But I used it for years, I liked it a lot, and it’s too bad that no digital SLR available today is as light and portable as the Vectis S-1 was.(*)

Launched in 1996, it was the only SLR system designed from scratch for the APS film format. It inherited the best features from the Minolta mid-range 35mm cameras of its time, and exploited the new functionalities of the APS format to its full advantage. Built around a new, specific and very modern mount, the Vectis cameras and lenses were far more compacts than conventional 35mm SLRs, and than the APS SLRs developed by Canon and Nikon.

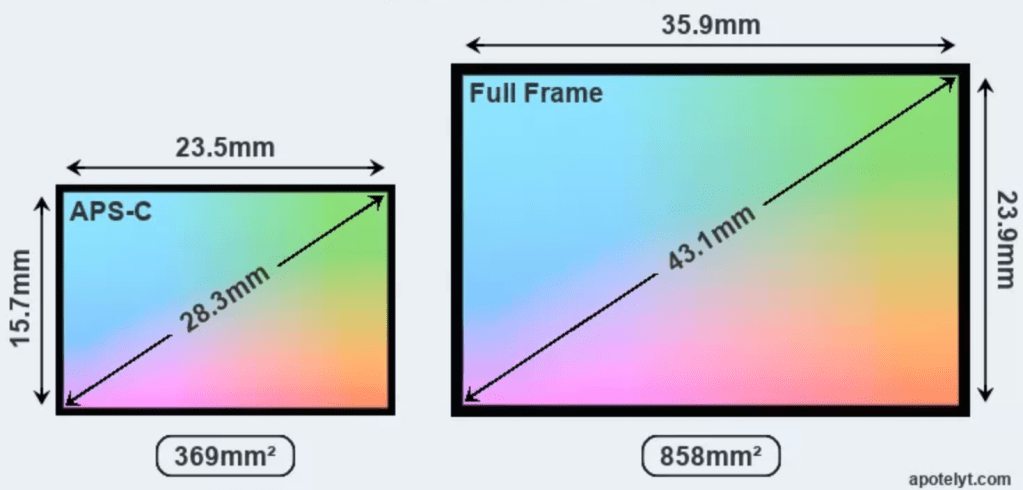

Single Lens Reflex cameras (SLRs) need a moving mirror, and the moving mirror needs room, which imposes a flange focal distance of approximately 45mm on 35mm cameras (44mm for the Canon EF, 46.5mm for the Nikon F mount). The diameter of the mount, on the other hand, is closely related to the size of the film (it’s roughly equal to the diagonal of the film – 44mm for the Nikon F mount, for instance). Both Canon and Nikon decided to make their APS cameras compatible with the large range of 35mm lens they had been selling for 10 years or more, and designed their APS SLRs around the same dimensional constraints (flange focal distance, mount diameter) as their standard 35mm offerings. Logically, the cameras could not be significantly smaller than their 35mm counterparts.

On the contrary, Minolta took the risk of making the Vectis S-1 totally incompatible with its own 35mm lens system – and opted for a shorter focal flange distance (38mm) and for a smaller mount diameter, without any mechanical linkage between the camera body and the lens. The body and the lens could be made much smaller, but Minolta had to develop a whole range of new lenses, and ended up supporting two totally incompatible product lines.

One could debate endlessly about who did the right thing, Minolta or Canon-Nikon. Minolta’s risky strategy did not pay off – the sales of the Vectis cameras proved disappointing, Minolta lost its independence and had to merge with Konica. But Canon or Nikon’s more prudent approach did not work either, altough they did not lose as much money with APS as Minolta did. Learning from the experience, Canon, Konica-Minolta and Pentax all decided to retain their 35mm mount on their new dSLRs with APS-C sensors. Only Panasonic and Olympus, with no legacy of 35mm AF SLRs, decided to use a smaller form factor with their Four-Thirds and Micro-Four-Thirds formats.

The design of the S-1 was very innovative in two important areas: it was not using the conventional central pentaprism, but a series of mirrors leading to a viewfinder implemented at the very left of the body – leaving space for the nose of the photographer, and the camera, its lenses and its accessories (such as the external flash) were all weatherproof, forming a compact, lightweight and reasonably rugged system that could even be brought in mountain expeditions.

The rest of the camera was in line with the advanced-amateur class of products of the time (P, A, S, M modes, Matrix and Spot metering, passive autofocus) and took advantage of all the new functionalities brought by the APS format – the ability to pre-select one of three print formats when taking the pictures being the most important. Some compatibility existed between the accessories of the 35mm cameras of the manufacturer (Maxxum or Dynax) and the Vectis: the flash system and the remote control could be used indifferently on both lines of cameras.

The user experience was very pleasant. Minolta cameras of the AF era have always been very pleasant to use, and the Vectis was no exception, provided you put the right lens on the body.

Unfortunately, the kit lens – a 28-56mm f:4-5.6 zoom, was not something Minolta should have been proud of. Poorly built, if proved fragile, and the quality of the pictures it produced was far from impressive. Mine broke rapidly, and I replaced it with a much better 22-80mm lens, which was correctly built, and could produce great pictures – with the right film in the body. The promoters of APS had decided that 200 ISO would be the “normal” sensitivity, but APS used a smaller negative than 35mm, and the quality of the enlargments from 200 ISO film never convinced me. The 100 ISO film, on the contrary, was very good. On a good bright and sunny day, with a good lens and 100 ISO film, APS could compete with 35mm.

My Vectis was defeated by one of design flaws of APS: the fragile automatic film loading system. A tiny piece of plastic broke in the camera, preventing the film door to open. Having it repaired was not an option. I sold the lens, and trashed the camera.

Today, the Vectis S-1 still has fans, ready to pay prices in excess of $150 for a camera. I liked mine as long as it worked, but with 100 ISO APS film now unavailable, I would not spend my money trying to get another one.

Good camera, flawed format. RIP.

(*): Edited in July 2017: the Vectis S1 tipped the scales at 365g, and the fragile 28-56 kit lens added 110g. With film and battery, the whole set was probably was below 500g. Today – in 2017, the remote heir of the Vectis, the Sony A6000, weights 20 grams less (at 345g). The Sony 16-50 Power Zoom also weights 110g.

More about the Minolta Vectis S-1

camerapedia.org: la page du Vectis S-1

collection-appareils.fr (site in French)

More about APS film in CamerAgX: