This is the other cheap camera I bought on Xmas eve on shopgoodwill.com. I paid less than $14.00 for it. The 2Cr5 battery it needed cost me more.

Launched in 1990, it was known to the North American public as the Photura, in Europe as the Epoca and in Japan as the Autoboy Jet. That’s the first generation model, and the one I bought.

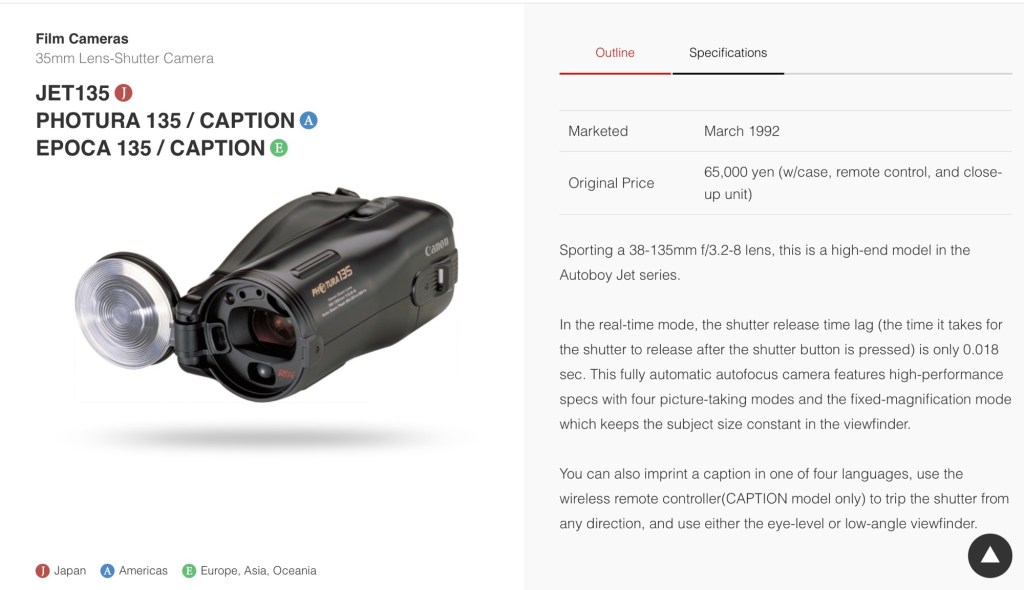

A second model (the Photura 135) was released 2 years later, with a zoom offering longer reach (38-135) instead of 35-105 for the original model and a darker body color. That’s the one presented in Canon’s virtual museum.

Because my copy of this camera was bought in the US, it’s a Photura, and that’s what we’ll call it it for the rest of this blog entry.

To this day, Canon’s official litterature still presents it as a top of the line camera.

Top of the line, for a point and shoot camera of its day: motorized 35-105 zoom, infra-red based autofocus, motorized film advance, drop in film loading, DX coding, dioptric correction, and all sorts of override modes for the autofocus – nothing’s missing.

The bridge cameras

In the late nineteen eighties (because they had missed the boat of the autofocus SLRs) , Ricoh, Olympus and Chinon started pushing cameras of a new type, that “bridged” the gap between conventional Point and Shoot cameras and Single Lens Reflex (SLR) . Like a Point and Shoot, they had a non removable zoom, and like SLRs, image framing was done through the lens. A flash was also built-in. It made for a large and heavy combo, but in the mind of the people who designed them, those all-in-one bridge cameras were supposed to be cheaper, less intimidating and easier to carry around than an autofocus SLR with an equivalent 35-135 zoom and a big cobra flash.

Because they tried to combine all the features of an autofocus SLR and its accessories (zoom and flash) in one compact design, the bridge cameras looked strange – and their form factor would not be widely accepted by the buying public before the beginning of the digital camera era – when the smaller size of the image sensor made much smaller lenses (and therefore much smaller cameras) easier to design.

The Photura was Canon’s late entry in the bridge camera category – except it was not really a bridge camera. Like a bridge camera it was designed around a 35-105 zoom, with an electronic flash (hidden in the front lens cover in this case) and a hand strap, but it was not a single lens reflex camera – the viewfinder was a simple Galilean design with variable magnification, similar to what you would have found on a point and shoot camera of that era. And the photo cell used for metering did not operate through the zoom lens, but through a separate tiny lens next to it. So did the infra-red autofocus system. Like on a point and shoot camera.

First impressions

The biggest surprise is how heavy (600g without its disposable 2CR5 battery), and how big the Photura is. Even considering that the zoom has a relatively broad range and that it’s rather luminous at the wide end (f/2.8 at 35mm), it’s shocking. It’s not as if Canon had integrated a constant aperture zoom in the camera – the aperture at the long end is only f/6.6, and and the reason why Canon recommended using 200 or 400 ISO film. To Canon’s defense, the (real) bridge cameras proposed by Ricoh, Olympus and Chinon were even bulkier and heavier, the Ricoh Mirai tipping the scale at more than one kilogram (2.2 lbs), with a lens less luminous than the Canon’s.

The second biggest surprise is that you don’t hold the Photura like you would hold any other camera. At least when you’re keeping the frame horizontal (shooting a landscape, for instance) and at the wide end of the zoom range, you simply insert your right hand between the body of the camera and the hand strap, and access the zoom rocker switch and the shutter release button with the tip of your fingers. Like you would do with a video camera. It’s not unpleasant, it’s just strange and a bit disconcerting.

The first experience is positive: the camera is reactive, the viewfinder is rather large, and it’s fun to use – for a point and shoot camera. Even if it’s bulky and heavy compared to most compact cameras, it’s still light enough that you can walk for one hour with your hand wrapped around the camera, which makes it a surprisingly discreet and convenient tool for street photography.

Unfortunately, the unconventional design doesn’t work as well if you’re a leftie, or if you shoot at the tele end of the zoom, or if you’re shooting a portrait and keep the frame vertical – you’ll need to hold the camera with two hands.

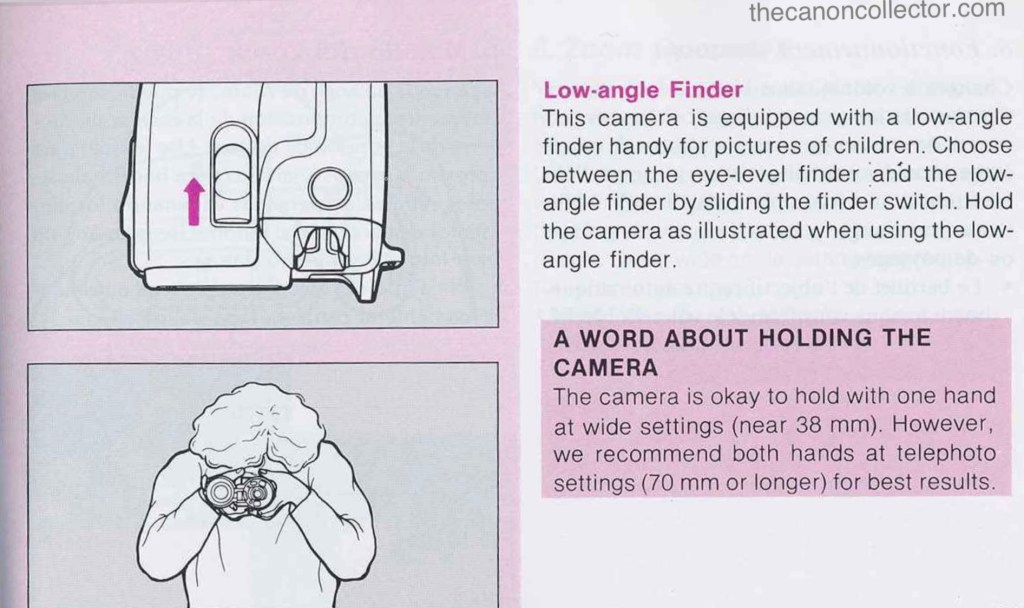

Another thing that does not work at all is what Canon calls the low angle viewfinder – it’s a second and very small viewfinder located at the top of the camera’s body – it’s so small you have to have your eye just above it (less than a centimeter) or you don’t see anything. In their user manual, Canon write that it’s to take pictures of children. Look at the posture of the photographer shown in Canon’s own user manual – the kids will laugh at the poor guy and will be gone before he can take the first picture. But it works if you’re kneeling, and trying to shoot something very close to the ground, like a very calm dog sitting in his bed.

Lastly, and maybe it was unavoidable with the technology of the day (and the price point being targeted), the autofocus system still seems to require a lot of work from the photographer: it can not focus to the infinite on its own – you have to force it by pressing a tiny button; it can not focus on tiny objects, and, because its detection zone is a rather small area at the center of the frame, you have to use an early form of AF lock if your subject is off center. Which is often the case if you shoot a portrait and want the focus on the eyes of your subject – not very amateur friendly.

That’s my biggest gripe with this camera – when it was launched in 1990, very good motorized autofocus SLRs were already available from Canon, Minolta, Nikon, Pentax and a few others, and their phase detect autofocus was already more efficient and reliable than what we have here. Their reflex viewfinder was incomparably better than what the Photura could offer – and you could see directly whether your subject was in focus or not (on the Photura you have to rely on a green/red LED that will simply confirm that it did focus on… something). And they also provided more control over the exposure. A Canon Rebel of the same vintage (with its 35-80 kit zoom) was not that much more expensive (only 10% more), was not that much heavier (if it even was), and would have been my choice without any hesitation if I had been looking for my first “serious” camera.

As can be expected, the Photura line stopped at the 135 model. Canon’s next big hit in the compact camera sector would have to wait for a few years, with the very small Elph/Ixus – one of few good APS cameras of the late nineties, which later morphed into the digital Elph, one of the first really good digital compact cameras in the early years of this century.

What about the pictures?

I loaded the Photura with a roll of UltraMax 400 and spent a few hours walking in an area of Atlanta named Cabbagetown. Its population has almost fully completed the transition from “working class” to “young urban professional” – Teslas, Porsches and Volvos are more common in the streets than old American iron.

I already mentioned that the Photura is a pleasant camera to carry around, and the images it captures are generally very good – sharp enough and correctly exposed – very few are technically deficient. I simply boosted vibrance and clarity to add punch to the pictures shown below. On the other hand, close-ups and interior scenes can’t be shot without the flash, which tends to over-expose massively subjects located at less than 4 ft.

All in all, I was pleasantly surprised by the Photura. I bought it as a curiosity, but the quality of the images it delivered impressed me. It’s an almost entirely automatic camera, with comparatively simple auto exposure and autofocus systems, and it works very well. Modern cameras will yield much better results indoors, but as a street and travel photography camera, it’s very efficient and a pleasure to shoot with. A keeper. Who would have guessed it?

Continue reading