New entry level interchangeable lens cameras can not be had for much less than $800 nowadays in the US, and that’s before the new tariffs start showing their ugly face on the shelves of the resellers. Giving a new Life to Old Gear and buying used equipment is the best answer in the short term.

We’ve seen a few weeks ago that early mirrorless cameras like the Panasonic G1, G2 or G3 can be had for less than $150.00 – those cameras are modern and pleasant to use, and the lenses you would buy for them totally compatible with the current micro four third (m43) cameras from Panasonic and Olympus/OM-System. But the dynamic range of the sensor leaves a lot to be desired.

In the same price range, an alternative is to look for entry level APS-C dSLRs. In that category, Canon and Nikon cameras abound, but a better deal can be found with Pentax, whose entry level dSLRs were well spec’d, and often available in very interesting colors. I recently found a “Gundam” Pentax K-r body at a good price in a Japanese eBay store (for those who are not in the know, “Gundam” is a Japanese science fiction media franchise, featuring giant robots painted in shades of blue, purple and yellow).

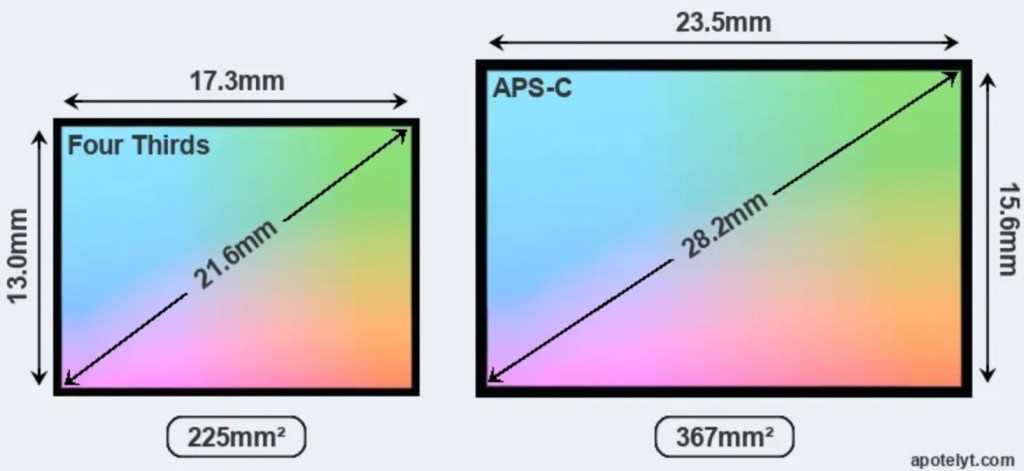

Launched in 2010 (like the Panasonic G2), the K-r is also a 12 Megapixel camera, but with a significantly larger sensor (APS-C) provided by Sony. Of course, and contrarily to the Panasonic G series, it’s a “conventional” digital SLR with a flipping mirror, and therefore the body and the lenses are larger and heavier than the Panasonic’s. The viewfinder is optical, and the autofocus of the “phase detection” type, as opposed to the electronic viewfinder and contrast detection autofocus of the Panasonics. Lastly, it accepts (with various limitations, of course) almost any lens graced with a variant of the Pentax K bayonet mount – even if it will give its best with Pentax DA, DA-L and DA Limited lenses, designed specifically for small sensor digital cameras.

Does the size of the sensor matter?

On today’s market, it will be difficult to find any interchangeable lens camera in the $100 to $150 price range with a resolution higher than 12 Megapixels. But 12 Megapixels is not that bad – it’s enough for a 8x10in (roughly A4) print at 300 dpi, and much higher than what is typically needed to share images on social media: most social media platforms downscale the imported images to bring them down to 2000×1200 points (approximately), when a camera like the Pentax K-r captures images of 4288 x 2848 pixels. Which leaves plenty of headroom.

There are more factors in the quality of an image than the resolution of the sensor: cameras of the K-r’s generation still needed a low-pass filter to control moire to the detriment of the resolution of small details, and the practical difference in image resolution between a K-r and a 16 Megapixel camera deprived of a low-pass filter will be higher than what a simple math would lead us to believe. The dynamic range of the sensor was also more limited, and the control of noise was more aggressive and not as efficient as what cameras launched a few years later offer.

Only one chance to give a first impression: the size of the camera with its kit zoom

For a dSLR with an APS-C sensor, the K-r is a small camera. And the body on its own is not that big. But mount a lens, any lens with the exception of a few Pentax pancake prime lenses, and it becomes a large object, that it will be impossible to store in the glove box of a car or a lady’s hand bag. If you stop at a bar or a restaurant, and you don’t carry a back pack, you will not know where to place the camera – on the table? hanging at the back of a chair? Nothing seems right. In that regard, it can not be compared to a compact digital camera or to a micro four thirds mirrorless camera like the Panasonic G2, that you can drop in the pocket of a coat.

That being said, the K-r is not heavy, its body is well designed with a big hand grip, the commands are logically placed, the LCD screen on the back of the body large enough, and it’s a very pleasant camera to shoot with. If only those lenses were not so large.

Only one chance to give a first impression: the viewfinder

Besides the size, the second thing that strikes you is the viewfinder. Again, after you’ve spent a few hours with the camera, you’ll find it perfectly fine, but if you’re used to shooting with a 35mm reflex, a full frame dSLR or a recent mirrorless camera with a high resolution electronic viewfinder, you’re in for a shock. The optical viewfinder is small and relatively dark, good enough to compose but not always to be sure you’ve captured the “decisive moment”. You really need to check the image on the display at the back of the camera to be sure it’s any good.

To Pentax’s defense, the viewfinders of their dSLRs are generally better (larger, more luminous) than what you find on equivalent Canon or Nikon models. And entry level mirrorless cameras in a similar price range (Sony NEX3, Olympus Pen) don’t have a viewfinder at all and require the photographer to compose on the rear LCD, as if using a smartphone. But when mirrorless cameras have an electronic viewfinder (an EVF), it’s not constrained by the size of the sensor, of the mirror or of the penta-prism. Even the Panasonic G2 with its comparatively tiny sensor has a large viewfinder, and provides an experience not dissimilar to the EVF of a full frame camera. Admittedely the image in Panasonic’s EVF is relatively low resolution and its dynamic range is limited, but it’s definitely showing a larger view of the scene than the optical viewfinder of an entry level APS-C camera.

Videos

Not the K-r’s cup of tea obviously. dSLRs in general are not very good at shooting movies, and this one is probably worst than average at that exercise – it only records 720p and autofocus is not available while shooting videos.

The ergonomics

The physical commands are organized more or less the same way as on the Panasonic G2 – one control wheel under the thumb, a few buttons to control sensitivity (ISO), over/under exposure, as well as AF and AE lock. Easy to use if you’re familiar with the modal interface used by most film SLRs since the mid nineteen eighties.

The unique selling proposition: in body image stabilization

One of the oldest rules of photography is that (on a hand held 35mm film camera), the shutter speed should never be slower than the focal length of the lens – if you mount a 28mm lens on your camera, 1/30sec is the minimal shutter speed that will avoid the blur caused by camera (and operator) shake; for a 135mm lens, the minimum speed would be 1/125sec., and so on.

That is, unless some form of image stabilization system is involved. Some camera makers (Canon, Nikon, Panasonic) have elected to equip some of their lenses with optical components that move inside the lens when a picture is being shot to compensate for camera shake. Other camera makers (Olympus, Pentax, Sony) have elected to move the image sensor itself while the picture is being shot. And more recently, both in-lens and in-body image stabilization have been combined to push the performance of the system to a higher level.

Pentax dSLRs – including their entry level models – have been equipped with a “Shake Reduction” system since the K10D of 2006. Because it’s an in-body system, it works with any lens, including manual focus lenses from the early K and KA mount era.

Performance

Pentax is a brand for money conscious traditionalists. Across the years, they have preserved the compatibility of their bodies with any lens they’ve made better than any other camera maker, including Nikon. It has its good sides, and its bad sides.

The autofocus is definitely old school. Even today Pentax bodies come with a DC motor to drive the focusing mechanism of lens – something that ensures compatibility with any Pentax Autofocus lens made since 1986. Nikon stopped offering this type of compatibility with the D3000, D5000 series and on the newest of the D7000 series, the D7500.

On the K-r, the autofocus system is generally accurate, but rather slow and definitely loud.

Image quality is very good for a 12 Megapixel camera, but the K-r is one of those old-school cameras that produce significantly nicer RAW files than JPGs. In the absence of Wi-Fi or Bluetooth connectivity (remember, this is a camera launched in 2010), the photographer will have to upload the pictures from the SD card to a photo management software (on a smartphone, a tablet or a personal computer) and will have the ability to process the RAW files before sharing the resulting JPEGs on social media.

Reliability

It’s now a 15 year old model, but nothing really bad has been reported in the Interwebs regarding the reliability of the K-r. As usual buy a camera with a battery and a charger, that the seller has personally tested: “I could not test the camera because it came without a battery or a charger” is a major red flag for me.

A reason I chose a K-r rather than a much better spec’d 16 Megapixels K-30 and K-50 is that those models are known for an “aperture control mechanism” issue, that renders the camera virtually unusable. A small part accessible through the lens mount (an easy to procure solenoid) is the apparent culprit, and DIYers confident enough in their dexterity with a soldering iron can attempt a repair and replace it. Definitely not for me.

Lens availability

The K-r is compatible to some level with almost any 35mm lens manufactured by Pentax since 1975, when they launched the Pentax K mount. Lenses released before 1985 won’t offer autofocus, of course, and won’t support certain exposure control modes. With a 42mm to K adapter, pre-1975 Pentax Takumar lenses can even be mounted.

You also have to remember that the K-r’s image sensor is smaller than a 35mm frame, and an old 28mm lens will have the viewing angle of a 42mm lens once mounted on the K-r. In the recent Pentax lens range, the DA lenses are designed for “cropped sensor” (aka APS) cameras like the K-r, and the FA lenses for the full-frame K1.

In order to address the issue of the size of the lens of dSLR cameras, Pentax has developed a line of very compact prime lenses, and (like almost every other camera manufacturer), a retractable standard zoom to make carrying and storing the camera less of a concern.

How much

As long as you’re ready to go for a black or white body, the Pentax k-r can be found at less than $100.00. The Japanese public could order almost any color combination for the body and the grip, and some models are really unique – but command prices up to $500.00, like this pink camo model below.

Because they’re abundant on the second hand market, Pentax lenses tend to be on the cheap side compared to the lens of other major camera makers. A 18-55 kit zoom can be obtained for less than $15.00 on Shopgoodwill.

As a conclusion: early mirrorless or mature dSLR?

For less than $150.00 for a body and its 18-55mm lens (if you’re patient and bid wisely), the Pentax K-r is a combination difficult to beat. Even the cheapest EVF-less 12 megapixel mirrorless cameras from Olympus or Panasonic will cost you more once you’ll have added a small trans standard zoom.

The image quality of the K-r is significantly better than what a Panasonic G1, G2 or G3 offers, and there is a wide choice of lenses available at comparatively low prices. The camera is pleasant to use and will be a good learning platform for photographers looking for their first interchangeable less camera.

But, like the Nikon D3000 series or the equivalent entry level Canon cameras, the K-r is also a representent of a dying category: the single lens reflex camera. All major camera manufacturers – except for Pentax – have moved on and launched mirrorless cameras and a new range of lenses, which offer much better video performance and are – for some of them at least – very significantly smaller and lighter than a conventional dSLR like the K-r.

Unless you’re sure you don’t want to shoot videos, you don’t mind the size, and you love the experience of composing your images through the optical viewfinder of a reflex camera, you have to wonder whether you would not be better off spending more (let’s be honest: at least twice as much) for an early 16 megapixel mirrorless camera from Panasonic, Olympus or Sony and its kit lens [*]. To a large extent, 16 Mpix represent the current sweet spot on the used market nowadays: images captured by a Panasonic GH3, an Olympus OM-5 or a Sony NEX-3 will be visibly better than pictures shot with the K-r’s, and your “investment” will be future proof. And yes, the early NEX-3 cameras were also available in interesting shades of pink, if that’s your thing.

[*] I did not mention Canon and Nikon’s early mirrorless cameras as a viable option in this price range. Canon and Nikon had both created and later abandoned a line of small mirrorless cameras (the Nikon Series One and the Canon EOS M). The early models (that can compete today on price with a Pentax K-r or a Panasonic G2 on the second hand market) were half hearted efforts not devoid of issues and I would not recommend them. Fujifilm mirrorless cameras came later than Panasonic, Olympus or Sony’s, and Fujifilm bodies and lenses are all in another price category. The image quality (out of camera) is outstanding, but the early models are handicapped by a really slow autofocus (X-Pro1, X-M1, X-A1). Later models that addressed those issues (X-Pro2, X-T1, X-E2, X-A5 and above) are also much more expensive, in the same price range as recent mirrorless models of the big three (Canon, Sony and Nikon).

More about the Panasonic G2 and the Nikon D700:

Other opinions about the Pentax K-r

DPReview’s review of the K-r: https://www.dpreview.com/reviews/pentaxkr

Pentaxforum’s review of the K-r: https://www.pentaxforums.com/reviews/pentax-kr/review.html

Pentaxforum’s review of one of the variants of the Pentax 18-55: Pentax smc da 18-55mm f3.5-5.6 al wr